We have a responsibility to grow our food with tools that enable us to live in harmony with nature

There has been an interesting debate recently in response to several articles by Dr. Jacqueline Rowarth, a soil scientist from New Zealand. Dr. Rowarth argues that forcing New Zealand farmers to reduce their use of synthetic nitrogen would cause declines in food production, soil organic matter, GDP, employment and biodiversity. She also argues that nutrients removed from the farm via harvest of crops or animals must be replaced with inputs from elsewhere, and we cannot sustainably mine those nutrients from the soil. In her words, “To access all the nutrients would require destruction of the fabric of the soil and of the organic matter that is so important in soil quality. As each year passes, nutrient supply is diminished and plant growth decreases, which means animal production decreases.”

There is nothing controversial about Dr. Rowarth’s comments in the eyes of many. In fact, this viewpoint would be considered best practices in conventional agriculture.

What is “conventional” agriculture, then? Any agricultural system is just a mindset or set of beliefs applied to the land, within the context of one’s local environment. What I’m calling conventional agriculture is the approach that became common after World War II, when cropping systems became heavily reliant on purchased fertilizer and pesticides. It’s a mindset that we can control nature and separate ourselves from it. It’s a belief that synthetic fertilizer and pesticides are essential for food production. It’s a belief that it’s often necessary to raise animals in confinement. It’s a belief that without this approach, much of humanity would starve. It’s a belief that problems with this approach can be solved with technology and engineering — or ignored and dealt with later. Ultimately, it’s a belief that we hold dominion over the earth, and we have a right to farm it as we please, regardless of the consequences.

The debate begins here: If you take the conventional viewpoint to its logical conclusion — where nutrients cannot be removed sustainably without synthetic inputs — it suggests that sustained food production is not possible. Think about it. How do soils form? How did biomass accumulate across the planet? Fossil fuel deposits aren’t a result of a few years of growth before the system fizzled out for lack of nutrient inputs. The earth grew trillions of tons of biomass and fed billions of animals over hundreds of millions of years without running out of nutrients for plant growth.

Soils formed because plants, fungi and other soil organisms “mined” carbon and nitrogen from the atmosphere and “mined” the remaining nutrients from soil parent material. Animals distributed nutrients across the landscape. This biological system was a self-reinforcing cycle of life. It was a planetary mining and nutrient recovery system that operated without human intervention. It all just magically worked. But how? We weren’t there to till the soil or spread fertilizer or spray chemicals.

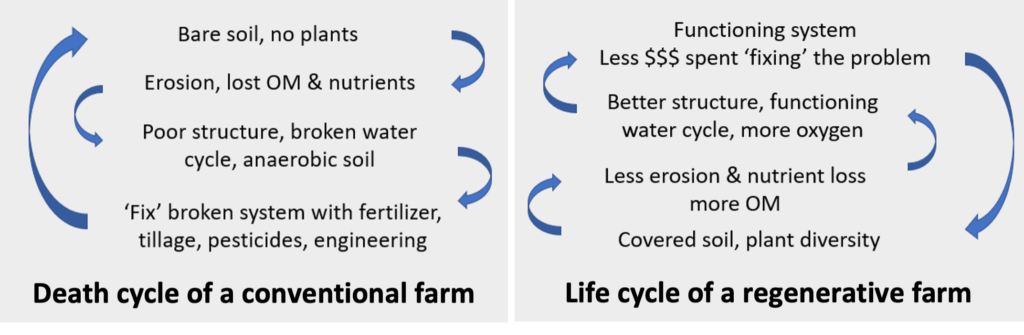

We know that this global “food system” worked just fine without us. This isn’t what folks in the conventional ag industry are saying, though. What they are really saying is that excessive tillage and reliance on synthetic inputs has resulted in broken nutrient and water cycles on a global scale. This approach degrades soil such that biological cycles no longer function properly. Concentrated livestock production puts too many nutrients in too few places. We congregate in cities far removed from where food is grown and flush away our “waste.” The result is an imbalanced system with nutrient-deficient farmland in many areas and a lot of waste, pollution and loss of productivity. We bring nutrients in from elsewhere in an attempt to fix the problem. The fix requires adding back a lot more than we remove at harvest because much of what we add is lost to the ocean or atmosphere or becomes tied up in the soil and is inaccessible to plants. It’s entirely fair to claim that synthetic inputs are needed in a conventional system. It can’t function without them.

The conventional ag industry response to all of the waste and pollution is that it’s mostly inevitable. We can do better, but our crop and livestock systems will always be “leaky” compared to unmanaged land. Some soil loss is tolerable. We can’t afford to do things differently. We are almost eight billion and counting thanks to the wonders of technology. It’s no longer possible to feed the world without confined animals and the fertilizer, tillage and pesticides that make the system work. Our fertillicide approach is becoming more efficient over time. Pesticides won’t cause problems because we won’t use them at unsafe levels. We will engineer plants that grow better in high-input, degraded soils and engineer solutions to capture some of the resulting pollution. Future generations will figure out how to deal with the rest. We know what we’re doing. Quit complaining about how we do it and be grateful that you have some affordable food on your plate. Deal with the consequences or go hungry. Your choice.

I believed this was the only path forward for most of my life, because it’s what I was taught by others with more knowledge and experience than I had. In the conventional ag world, regenerative agriculture is seen as wishful thinking or just plain crazy, rather than a feasible alternative for global food production.

What is regenerative agriculture, then? It’s a mindset that we cannot control nature or separate ourselves from it. It’s a belief that we can grow enough food without degrading soil and polluting the environment. It’s a belief that we aren’t going to engineer a solution better than what mother nature figured out millions of years ago. It’s a belief that using fertillicide and industrializing our meat production is a choice, not a necessity. It’s a belief that synthetic inputs should be a last resort, not the first tools we reach for. It’s a realization that we will eventually lose our current war against diversity on the landscape. Ultimately, it’s a belief that we are part of nature, and we have a responsibility to grow our food with tools that enable us to live in harmony with it to sustain life on earth.

Fertillicide

Definition: Excessive use of fertilizers, tillage, or pesticides as a means to control nature in pursuit of food and wealth, ultimately leading to the demise of civilizations due to the degradation of ecosystems that support life.

Regenerative agriculturalists have a different viewpoint. Something — often an economic or health crisis — has caused their worldview to shift, or they may be new to agriculture and open to different approaches. They started to do their own research and learn things that weren’t taught in agriculture programs. They started looking at the big picture and asking uncomfortable questions about our current food system. They started turning to nature for answers. Rather than accepting the consequences of our current system, perhaps we should acknowledge that the problem isn’t that our soils are incapable of producing enough food without the conventional approach. Perhaps the problem is our management. Perhaps we should address the underlying problems rather than treating the symptoms with purchased inputs and engineering fixes. Perhaps our current food system and its accompanying environmental degradation is actually a choice rather than an inevitability. Perhaps we don’t need to do it the conventional way.

In short, regenerative agriculturalists believe there is a better way to grow food and are setting out to find that path. Conventional agriculturalists are saying it can’t be done and that the path does not exist.

It is not crazy to believe that we can produce enough food without fertillicide. Crazy is watching our soil — the foundation of life — erode away for the sake of short-term profit. Crazy is applying toxic pesticides that end up in our food and water. Crazy is thinking we can keep doing this. Conventional agriculture is ultimately a denial of the reality that fertillicide is destabilizing life-supporting ecosystems and is incompatible with future human flourishing. We trade soil for yield, degrading the environment in the process. Every argument I’ve heard for why we need fertillicide ignores this simple fact. The problem is too wicked to deal with, so we bury our heads in our degraded soil while we watch our vitality erode into the seas. Humans are supposedly the cleverest beings ever to grace the earth, yet we can’t grow our food without destroying the thing that allows us to live? I believe there is a better way.

We are just beginning to understand how to harness the power of biology rather than relying on chemistry. It is possible to reverse soil degradation and improve productivity at the same time. We have vast untapped potential to capture more photosynthetic energy to boost yields. Our current cropping systems are wasteful of sunlight, water and nutrients that can all be better utilized in a biologically based system to produce abundant and healthy food. We waste billions of dollars every year propping up our current unsustainable system that costs billions more in environmental and health damages. If we invested that money instead into regenerative food systems, we would be well on our way to a secure food future. The conviction that we need fertillicide to feed the world is simply a resistance to change and a protection of the status quo that profits from it.

There are three common critiques to the idea that we can produce enough food without the conventional approach. The first is that we don’t have enough land to do it. Some practices that improve the soil do reduce yield, at least in the short term. But there is nothing inherent to regenerative management that requires more land in perpetuity. We will learn how to improve production as we transition away from conventional methods. We currently use millions of acres to produce ethanol — a system that results in more soil loss than grain production, just so we can drive to the store to buy food produced somewhere else. You can judge whether this is a wise use of our cropland. The point is that we have enough land. We can choose to produce food on it or not.

The second critique is that regenerative practices require too much labor. In a world where jobs are being automated away, perhaps a food system that creates jobs rather than eliminating them would be a good thing. Perhaps creating opportunities for people to live and work in rural areas might help revitalize our rural communities. Sounds like a feature, not a bug.

The third critique is that it would make food too expensive for many people to afford. Regeneratively grown food is more expensive, mostly because it’s a niche market and our current food policies are designed to subsidize conventional production. Regenerative production costs will decline over time relative to conventional. Sunlight, air and rainwater are free. A system that maximizes their use rather than relying on increasingly expensive inputs to offset problems with bare ground and poor air and water exchange will be at an advantage. Eventually the chickens come home to roost and we will have to pay the full cost of producing our food. We could choose to support a regenerative food system and keep food costs low using the money that currently subsidizes conventional production and that pushes the social, health and environmental costs elsewhere so they aren’t reflected in the price we pay at the store.

In short, none of these critiques hold water. They are just more narratives pushed to resist change and protect the status quo.

Most regenerative agriculturalists are also realists. They admit that we haven’t figured out how to produce all our food regeneratively and that it will not be easy. They acknowledge that they are somewhere on the spectrum between conventional and regenerative. They accept that there is no “right” way to farm — just difficult choices to make. Realistically, it will take decades to transition all our land to regenerative management. We will need to add carbon and biology while we wean our soils off the synthetic drugs that keep them in a stupor. We will need to stop forcing weed-free monocultures into a biological system that will never stop fighting against them. We will need to raise livestock in a way that doesn’t concentrate too many animals in too few places. Our city infrastructure will need to be redesigned so that our waste is converted to humanure and returned to the soil. Nature can show us the way.

We will always impose our management upon the land in order to grow food, but we can do so in a way that doesn’t threaten our survival. We choose how we manage our land. We choose which path to take. Our future depends upon the soil winning our conventional war against it. Soil is alive and fighting to survive. It does not need synthetic inputs to be productive. It needs us to stop fighting back. It needs its plant partners to cover its bare, sunburnt skin and help it heal. It needs its microbial friends to help it breathe and eat and drink and communicate with the world. It will communicate with us and show us the path if we take the time to listen. It will tell us how to grow plentiful food without committing fertillicide. It will tell us how to inhabit a world where we don’t need to destroy our home in order to live in it.

Brian Dougherty is an agricultural engineer and 2018 Nuffield International Farming Scholar from Dubuque, Iowa.

How do you define “regenerative agriculture”? Let us know via:

- Email: editor@acresusa.com

- Social Media: Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn

- Mail: P.O. Box 1690, Greeley, CO 80632