How one grower found success by simplifying his operation

Balance between work and personal life is elusive for most people. For farmers it can be even more difficult, with the place of work often overlapping with the home.

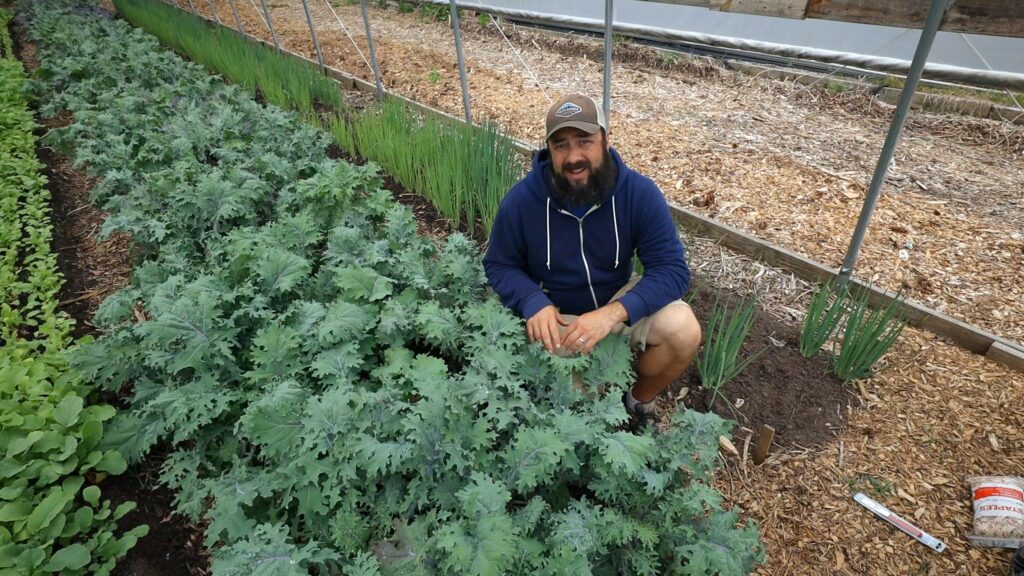

Josh Sattin is one grower who seems to have achieved some level of positive equilibrium in this regard. His solution is multifaceted. It began with streamlining his operation in terms of equipment and setup and limiting his marketing outlets. But the real innovation was in determining to only farm part of the year — taking the hot, humid North Carolina summers off and growing the rest of the year in tunnels.

In this conversation, Josh and interviewer Diego Footer (paperpot.co; Farm Small Farm Smart, Grass-fed Life and Carrot Cashflow podcasts) discuss why and how Josh got into farming, farm work-life balance and the basics of his farming system. They also introduce a free online farming course that Josh recently produced.

Acres U.S.A.: Josh, it’s late-January 2022. For you as a farmer, what’s going on this time of year?

Josh Sattin: It’s pretty balanced right now. I’ve actually switched to farming off of the regular season. I’m not going to be farming in the summer. So, this is my season. I’m in Raleigh, North Carolina, which is in zone 7B, and we have pretty mild winters here. I’m growing and harvesting every week right now, but the pace has slowed down significantly.

I harvest once a week. I’m planting when I can. I’m not really putting in that many hours right now. Once we get closer to spring, things will start ramping up.

Acres U.S.A.: For a veg farmer in North America, it’s kind of unusual to not be farming over the summer months. What was your thought behind that?

Sattin: It’s a decision that was a few years in the making. First of all, I’m in the South. The summers are very rough here. They’re very humid. They’re very hot. The crops I grow don’t do well in the summertime. I’ve struggled through enough summers where I get poor yields. I get pest pressure — all those kinds of things that make me not want to farm.

Also, physically — being outside in the summer, I’m in my early forties and I don’t want to be out farming in the heat. After about 11:30, I really can’t be outside.

I’m growing 100 percent under plastic right now in caterpillar tunnels. It just made more sense to farm all winter and have a really strong spring and then take the summer off.

Also, my kids will be in middle school next year and they’re going from a year-round school, which is common here, to a traditional calendar. So they’ll have the summers off. I decided to take the summers off, not stress about growing, hang out with the kids and do other projects.

Once I made that decision, it was like a whole load was lifted, because last summer was really brutal. And I also look to farmers farther South than me to see what they do. Like Eric Schultz, for example — I know he doesn’t farm all summer.

I’ve talked to growers in Florida as well, and I think this trend is going to continue. I also talked with David Williams at Sunset Market Garden here in North Carolina. He originally started with just winter farming — not summer farming. His motivation was to get to market earlier and have crops when other people didn’t.

Acres U.S.A.: You’ve really molded farming to life. I think a lot of entrepreneurs have trouble doing that. They feel the pressure to grow, to earn more, to expand, and they do it sometimes at the expense of family — at the expense of their own health and wellness, their own sanity and the joy of why they started doing it in the first place.

How have you gotten to this point where you’ve adjusted farming to life? I don’t think everybody could pull that trigger.

Sattin: For me, it’s a little bit different because I’m not a full-time farmer. I think that definitely enters into the equation, because I have to balance both what I do with my time professionally and also income for my family. I spend a lot of time creating online content. I have two YouTube channels. I do other videography work. The farm is a part-time job, so it’s part-time income as well.

You can’t start thinking about this kind of change until you have your systems dialed in — until your farm is organized, you know how to grow things, you know how to sell things.

I had to make it work — otherwise I wouldn’t be farming. There are always sacrifices, but it’s really easy when you get into farming to work super hard and quickly burn yourself out.

Trying to find balance is huge. If we don’t find that balance, we’re not going to be farming down the road.

Acres U.S.A.: I think there are people out there that might look down on someone who’s not farming full time. If somebody chooses to farm part-time, what words of encouragement would you give them to say, “Who cares what anybody else says?”

Sattin: There’s been a lot of criticism about that. I made several videos about part-time farming because there’s this whole stigma about farmers and farming — that you need to work a million hours and work yourself to death.

Nothing in life is an all-or-nothing situation. You can mix and match things. You can do a little bit of this, a little bit of that. Some people are home gardeners, but they might want to get into farming. Well, why don’t you get into farmsteading? Why don’t you just sell some crops and still have a job?

I think there are a lot of ways you can do that. When you’re looking to start a farm business, you need capital — like with any business. Do it part-time for a while, see if you like it, take all the money you make from that and then reinvest it into your infrastructure for your business.

Maybe in a couple of years of part-time farming you’ll have enough money — and you’ll have the sales outlets — that will allow you to go full-time if you want. Or just stay part-time. Do what makes sense for you.

Acres U.S.A.: I’ve always been a big proponent of designing a life that you want to live. Maybe a spouse earns the predominant family income. What’s going to work best for your family? Farming doesn’t have to be everything. Sometimes people are so dogmatic that farming has to be the sole income, but that doesn’t work for everybody. Diversifying into some of these other channels — YouTube, or teaching, or an off-farm job — that can just make life more enjoyable for people. And it can actually work better than trying to work that million hours on the farm.

Sattin: I agree. You could have a job doing whatever. If it’s a job that pays really well, but you’re not super into it, then you can put all your passion into farming. That works as well.

What I realized for myself was that I think I can have more of an impact in the farming system — in the food system — by helping teach people. I’m a former educator. I taught high school for five years a few careers ago.

People give me that criticism — like, “If this is profitable, why don’t you just scale it up? Why don’t you get employees? Why don’t you build the business?” And I tell them, it’s really simple right now. I can manage it. There’s very low stress for me. I can spend that time helping other people who want to do this either part-time or full-time. So that’s how I’ve been justifying it.

But you don’t need to justify it. If it makes sense for your family, just do that. That’s what’s important — if you enjoy farming, but you don’t want to do it full-time, that’s totally cool.

Acres U.S.A.: How do you define success when it comes to farming? Because it’s interesting that you say that farming is low stress. I think the perfect job is the one that supports the lifestyle you want to live while inducing the least amount of stress possible. That’s the best combination — the overlap you want.

Sattin: Anytime you’re talking about success, you have to figure out what your goals are. So, some farmers are donating food. Some farmers are trying to grow what they like to grow, for their family to eat, and then they sell whatever’s extra to cover some of the costs.

I’m just trying to make some of my family’s income from farming, and I’m not going to stress and say it has to be a certain number. I don’t have that specific financial goal. For me, it’s about maintaining the farm, bringing food to restaurants every week and using my farm to teach and educate and share what’s going on.

A big part of my farm is being able to show people what I’m doing and use it as an example to let people see what works and what doesn’t. I’m more than happy to show people what fails on my farm.

When I started farming, there was no content I could find coming out of the South in terms of market gardening or vegetable farming. It was all coming from either the Pacific Northwest or the Northeast or Canada. Putting that content out, I think, has been really helpful for a lot of growers out here — to see what’s possible. I have a two-acre lot in the suburbs and I grow on an eighth of an acre — that’s my whole farm. It allows people to see that you don’t need a ton of space to do this.

That’s wrapped up in my success — not just the financial stuff. There’s financial capital and social capital, and they’re both important to me. I don’t have a set goal, but lately I’ve been feeling successful.

Acres U.S.A.: Has that evolved since you started farming?

Sattin: After teaching I was a professional brewer for five or six years. And after being in that industry for a while, I needed a change. We bought this property and I thought, “We should get some chickens. And we should learn how to grow vegetables.” So I did some research and realized that the best vegetable growers were the market gardeners. That system made sense to me. I set up a couple of beds and I planted a whole bunch of stuff, and it was like, “Oh — there’s a lot of food!”

And people started wanting to buy it from me — family and friends. So I started a box program, and it went on from there.

Acres U.S.A.: Can you give us a picture of what’s on your farm?

Sattin: This is my third time building a farm in the course of four years. I’m using no-till practices, a deep-compost mulch system and a market-gardening style. Thirty-inch beds, usually 50 feet long.

The first iteration of my farm had almost 30 beds. I also had some chickens. A lot of microgreens, too; when I started, there were all these enterprises I wanted to play with and figure out what worked and what didn’t.

It became too much at the time. I was being pulled all over the place and nothing was really thriving. It was doing everything at the same time. After two years I got offered an opportunity to run Raleigh City Farm, a non-profit farm in downtown Raleigh. I got brought in to manage the farm, but we basically rebuilt the whole farm from scratch, and it was incredibly satisfying and a lot of hard work. After a year there, it was not the right place for me anymore. I came back home and rebuilt the farm using all the experience I gained in the last three years of farming.

I built three 100-foot caterpillar tunnels, and I’m growing 100 percent under cover. That has been an absolute gamechanger because I don’t have to stress about heavy rains, which are a big problem for us here in the South. We’ll get 3 inches of rain in a couple hours, and all of a sudden all of your beautiful soil is washed away.

In addition to those three tunnels, I have a really nice nursery greenhouse that I do all my starts in. And that’s pretty much it. My wash-pack is in my garage. It’s really a suburban farm.

I’m still using the 30-inch by 50-foot bed system. One of the things that’s really great about my farm is the systems I have in place. I’ve learned that it’s really important to streamline everything. I have multiple-zone overhead and drip irrigation in all my tunnels; I have a really nice composting setup; everything’s well mulched; there’s no crap laying around; everything’s organized; my tools are right next to my tunnels. I’ve set it up in a way that is successful. I want to spend as little time as possible farming — not because I don’t like doing it, but I don’t want to waste time doing that when I could be doing something else, like working on video projects or hanging out with my family.

It’s hard because when you grow under plastic, aesthetically, it looks awful. You just see three big greenhouses out in my backyard now, versus open beds. But when you have that control of the weather and temperature to some extent, you get a lot more success, and I’ve had way bigger yields and way more predictable results than I ever had before.

So that’s what my farm looks like now. It’s very simple. I only grow four things at a time.

Acres U.S.A.: You started without much experience. Then you started a new farm with a lot more experience. When you rebuilt the farm for the final time at your place, you added tunnels. Were there any other big things that you learned over the past few years that you incorporated?

Sattin: One of the biggest things that people often overlook is drainage. I talk about this a lot because it can really screw up your farm.

I’ve talked to a lot of farmers, and I’ve done a lot of consulting with farmers, and I always talk about drainage, because people don’t think about it. They’re like, “I’m just going to put down soil and build deep-compost beds and we’ll be off to the races.” But if you don’t figure out where the water is going to go, it’s going to take all of your soil with it.

We get crazy rainstorms here in North Carolina, and drainage is something we really thought through. Before we built the tunnels, we planned out where the water was going to go. We put in ditches that are off contour so that when it rains, all of the water can drain away as quickly as possible. So that’s one thing I’ve learned from farming on two different properties — that drainage is a huge concern.

Another thing is setting up systems and streamlining them. How you flip beds, how you transplant, how you harvest, where the tools get stored, etc. This came into effect big time when I was at the non-profit farm, because I was training farmers. I needed to have all the systems dialed in, because I wanted to make sure that everything was as simple as possible for them. If we could get rid of a tool, if we could standardize things, we tried to do that.

For example, the gridder is a very simple tool, but adding that into the mix is huge. When you have volunteers, you can tell them to go plant lettuce with the four-row gridder. There’s no question about spacing — just plant them where the gridder tells you. It gives you as much control as possible.

In terms of tunnels, I mentioned irrigation. I have drip and overhead in multiple zones. It just makes the farm work easy. Everything should be near each other. Don’t have a lot of clutter laying around. I have nice big pathways that are mulched around my tunnels and near the compost bins.

Any time you can take control back when it comes to farming, it’s good. You’re up against so much that you can’t control — mother nature, pests, disease, weather. So pull back as much control as you can. Low-key infrastructure like caterpillar tunnels—not the most expensive things out there, compared to really high-tech high tunnels.

Acres U.S.A.: I’m curious on your thoughts on this. There are people who want to absolutely bootstrap a farm and not spend any money to get it started. And then there are people who retire from some other career and they have plenty of money and they start up this really high-tech farm.

What are your thoughts on somebody new getting into veg farming and what infrastructure is required — a realistic view of what it’s going to take?

Sattin: I love this conversation. It depends on where you are, of course. I don’t necessarily think that in certain contexts you need to have caterpillar tunnels, but in a lot of places I think it’s crucial. I think the best ways to invest your money when you get started is tunnels and soil. Everything else doesn’t really matter to me.

I started with two tunnels and I just added a third one a couple months ago. You can buy a caterpillar tunnel for $2,000. With soil and irrigation you get to about $3,000 per tunnel. But if you think about a bed of lettuce, one 100-foot row can yield $600 to $800. So that tunnel’s paid for in just a handful of bed flips. Realistically, of course, when you first start, you’re probably going to get a third of that yield — you’ll improve over time. But to me, the best investments are tunnels and soil.

I’ve eliminated a lot of tools. I think you need a broadfork. You need a good rake. I think a Jang seeder is non-negotiable if you’re direct seeding anything. I love my tilther, but do you really need it? No.

So, there are a couple of big purchases, but generally just invest in soil and tunnels and have a good wash station. If you’re doing greens, if you don’t have a good setup for that, you’re going to waste so much time. You’re not going to make any money and will kill yourself trying to get your greens processed.

Focus on systems, learn how to grow food, and control as much as possible.

If you can’t develop soil yourself by cover crops or making your own compost, just buy compost. I bought about 90 yards of compost in the last year. I’m going to pay the money for that, because to me, the soil is the most important thing. So that’s something I truly invested in. The tunnels protect the soil so it doesn’t wash away. And you can maintain that.

Acres U.S.A.: Although, we have to be careful about giving the soil nerds a blank check to improve their soil! Where do you think the limit is? I want to go supermarket sweep down the aisle and buy all the cool soil amendments, too — and I don’t disagree with you that soil’s fundamentally important — but where’s the practical place to start? Because it’s easy to get focused on soil, but you’re in business to grow crops. You can lose sight of the other parts of the business. Soil is a pillar — it’s the foundation that helps us do what we do — but we’re not soil growers at the end of the day; we’re plant growers.

Sattin: There’s a lot of approaches here, but when you’re on a small scale, you don’t have time and space to be cover cropping. I might cover crop some of my beds in the summer when I’m not growing, but I don’t have time for that during my growing season. I need to produce as much food as possible.

I’m going to pay to bring in what I need. When I built my beds, I was lucky that my local composting facility does a mixture of half leaf mold and half compost, which is amazing for starting beds. When you’re doing a deep-compost mulch system — a no-till sort of style — you’re putting down a whole bunch of material. When you buy straight compost, it’s way too nutritious. It’s way too high in nutrients and minerals. Straight compost should be used as an amendment, not as a soil. I was lucky that I was able to build my beds with that mixture, and it’s been awesome.

I also have no problem paying for dry amendments and using those on every bed flip. I’m adding a little bit of compost and some amendments. It’s one of those things where you can spend all the time and energy you want bringing in materials and compost and doing cover crops. To do that, you need to have a lot of equipment. You probably need a tractor to move material around. You have to figure out how to get that material to your property. Market gardening in general is an export game. We’re constantly sending stuff off our farm. So we need to bring stuff onto the farm to make up for that.

I just pay for it, because my time is worth so much. I’m not as good of a composter as the professionals, so I just buy it from them.

The things that I focus on are bringing in as much organic material as possible. I focus on all the things to create living soil: keep the ground covered, keep the ground planted, disturb as little as possible and create diversity. Those are the four things that I try to follow as much as possible to create living soil. I’m constantly feeding the soil with amendments and compost and keeping biology going by having plants growing.

That’s when the soil just takes off. I’m about a year into some of my beds at the farm here, and the soil is just incredible. So that’s my approach — you can treat your soil well and still be harvesting off of it, but you have to feed it all the time and take care of it. You can have high output and also keep your soil happy.

Acres U.S.A.: Can you give a brief overview of deep-compost mulch?

Sattin: Basically, you just add a crapload of soil and grow in that. When you put down a whole bunch of material, you have instant beds because you put down so much material; but you’re also using the compost as a mulch on the surface.

So you don’t have the weed pressure that you would normally, and you’re not tilling, so you’re not bringing weed seeds up to the surface. Farmers normally till before they plant, and then three weeks later they have a huge flush of weeds because they brought all those weeds up to the surface. We don’t have that.

To get started with this process, tarping is generally the best method to kill everything that’s growing. Then you lay down a bunch of material, and there are a lot of different options for that. Basic lasagna beds are the most common way. You layer carbon with compost, or you can do multiple layers. I use cardboard because there’s plenty of cardboard around here, being close to a city, and then I buy my compost. But you could use straw if that’s available.

The best thing is to do all that work up front by killing everything by layering on a thick layer of soil. As I said, leaf mold is a great mix with commercial compost, and then you have soil you can plant into.

I have solid clay soil here — the red stuff you can make a pot out of — so you have to be mindful again about drainage. If you laid down a bunch of materials, water’s going to go through that really nicely, but then it’s not going to penetrate the subsoil. So you can’t grow all the crops you want right away — good luck trying to grow carrots on 4 inches of compost. It’s not going to work if you have really hard soil underneath.

There are a lot of things that you have to think about when you’re using a deep-compost mulch system, but that’s the idea. You put down a bunch of material and you can get started with that. And that acts as a mulch to the ground below to try to keep the weeds off the bed.

Acres U.S.A.: Do you think it’s a practical system for market farmers?

Sattin: Yeah, it’s great. You can get started really quickly and have big yields. There are a lot of things to consider. The biggest one is getting material, because it’s not available everywhere.

Getting good compost in a lot of places is really hard. It can’t have any residual herbicides or pesticides. It needs to be free of weed seeds. If you can find this type of compost, it’s expensive. But we talked earlier about how I think it’s a very valuable resource to be adding to your farm.

I’ve even seen this method on large-scale farms. There are guys doing this on big acreage. It is possible. But you have to think about it differently. It’s a great way to infuse a lot of organic matter and get the soil life and soil biology started and grow really healthy vegetables. I think it lends itself to the kind of farming I do — I use zero pesticides, herbicides, insecticides.

Acres U.S.A.: How do you set up market streams with this type of a farm? I think people assume that if they’re going to sell to restaurants or go to a farmers market, they need a lot of land. Obviously, you want consistent product — your customers expect a certain amount of product all the time. How do you find a customer base for this kind of smaller, more niche farm?

Sattin: There are a lot of different sales outlets. I’d say selling retail is going to be really hard. A supermarket is going to be really hard with a small scale. And when you’re selling wholesale, the price is going to be much lower.

I think a CSA is not a good model for small farms. You need a much larger farm, because you have to grow vegetables that have lower value so that you can have those in the boxes, and you have to grow a much wider variety of crops. You need six to ten different crops every week for your customers. If you have a small farm, it’s really hard to grow a large variety.

I think it comes down to the last two options, which are farmers markets and restaurants. I think markets are the best way to get started, because you can literally just show up with whatever you have and try to sell it. Or setting up a little farmstand table outside of an event, or a roadside stand — something where you can just roll up with what you have and sell it.

I’m selling to restaurants only. This can be tricky, because most restaurants want the same thing every week, except for seasonal items. I have certain restaurants that want 12 pounds of lettuce every week. Over time I’ve built relationships with chefs and restaurants, and they understand the small-scale seasonality and realize how good the food is, and they want to support me. Then it becomes a different thing, because I’m working with them and getting the restaurant what it needs. Like, if we get a cold snap, I can text my chefs and say, “I’m sorry, my kale looks terrible this week.” They understand that, because they’re willing to work with local farmers.

Acres U.S.A.: You shut down over the summer. How do you think your customers feel about that?

Sattin: I’ve talked with them about it. It’s about those relationships — communicating well with your customers and saying, “I’m not going to have this during this time. I need to let you know that now so that you can plan around that.” If they really like you and value the relationship and what you bring to them, that’s important. If I lose a customer, I’ll find another one. There’s such a demand for this in my area that you just figure it out. It’s one of those things — there are going to be sacrifices; if I have to make a sacrifice and lose a customer during the summer, then that’s what happens.

Acres U.S.A.: I think a lot of people like your model of farming. It resonates with them because it’s less intimidating. But there are a lot of market farms that publicize how much they can make on an acre. And that’s great because it shows what’s possible. I’ve talked to enough farmers to know you can make hundreds of thousands of dollars on an acre — that’s not a BS number, and there’s a significant profit in that. So that’s good, because that means you could make a good living farming if you want to go that route.

But the bad thing about those numbers is that people either expect it on day one or they’re intimidating, because they think they can’t get there.

How would you get somebody to think about farming and the income that comes from it?

Sattin: People see those numbers and they want to get there. I think that a beginning farmer should expect about a third of that at first. When you first start growing, you’re going to have a lot of mistakes, and your soil is not going to be there, and you don’t know what you’re doing most of the time. There will be a lot of crop failures. I think that’s a realistic approach.

Also, remember that those farms have a lot of workers. It’s not one dude in his backyard. Clearing $300,000 an acre — that’s a much larger operation with many employees with multiple sales outlets and a staff, and that’s a much more complicated business and operation. You have to put that in perspective.

A lot of times farms expand too quickly because they’re selling out of everything, and so they keep building beds. All of a sudden, they’re like, “Okay, I need three employees.” And then are they making more money? I don’t know, but I suspect a lot of times they’re not until they get to a much larger size, and then you have a much more complicated farm.

That gets back to the stigma about part-time farming or making this much money. It’s what makes sense for you. What are your goals? I think that’s really important to think about, because we all compare ourselves to everyone. When we go on social media or on YouTube, other farmers have different contexts. They have different sales outlets. They’re charging different prices. The cost of labor is different. They have different kinds of labor. These guys have been farming for 10, 15 years. A lot of them really know what they’re doing. They’re the outliers. It is possible, but most of us are not at that level. So just keep that in mind.

Acres U.S.A.: One thing you’ve stressed is that you want to find a way to help educate people. You started putting out YouTube videos because there weren’t videos of people farming in your area.

Now you’ve put together the Sattin Hill Market Farming Course, a series of videos that’s airing for free on your YouTube channel. Can you talk a little bit about why you put this project together?

Sattin: There are a lot of courses out there, and I’m not going to say mine is better or worse than anybody’s. I’ve been thinking about doing this for a while, but I didn’t want to charge for this content. I think this information needs to be out there for free and it needs to be accessible, because if we’re going to make a difference in the food system, we need to have as many people learning how to do this as possible. So I’m really thankful for Paperpot Co (paperpot.co) for sponsoring this and collaborating with me on it.

Most of what I’ve experienced and learned and taught is on my YouTube channel already. But in the nature of YouTube, it’s so scattered. It’s really hard — if you told me, “I want to learn how to farm this year,” I’d have to say, “Okay. Go watch my 250 videos. There’s a little snippet in each of them that you’re going to need to know.”

What we’ve done is to consolidate all that information down to about 20 videos and made it really clear and concise and packaged together. Everything that I’ve learned and experienced and know about farming and all my systems that I’ve put in place to run a small market garden that we’ve been talking about is there. People can watch it and get the information as quickly as possible and as clearly as possible.

I have a background in high school education. I did that for five years. So teaching is right up my alley. I absolutely love it. I’m excited to make this possible so that it can be a resource for everybody.

| Learn More You can access Josh Sattin’s free market farming course at paperpot.co/josh or on YouTube. The course is sponsored by Paperpot Co (paperpot.co), where you can also check out Diego Footer’s popular farming podcasts: Farm Small, Farm Smart; Grass-fed Life; and Carrot Cashflow. Learn more about Josh at joshsattin.com. |