My dream for a new kind of agricultural exceptionalism in America

Before describing my dream for a highly diverse, localized farm system, I’d like to address three issues that I believe are hindering the adoption of regenerative agriculture here in the United States and worldwide.

First, the elephant in the room: agricultural exceptionalism. Much has been written about this concept, but here it is in a nutshell: “agricultural exceptionalism” is the pervasive notion that because food production is so central to human survival, agriculture should be entitled to special legal and regulatory advantage.

Beginning with the first Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933, Congress and the courts have built a safety net of statutory exclusions and economic subsidies to support what has become known as “conventional agriculture”: large-scale, highly mechanized, monocultural plant and animal production. The intentional result of this safety net has been a bouquet of special entitlements enjoyed by members of almost no other industry.

As long as this situation persists, conventional food and agriculture will remain unburdened by the true costs of production. These costs, inclusive of ecological, social and healthcare costs, have been socialized through regulatory exemptions. The costs of weather and market risks have been socialized through subsidies. This makes food artificially cheap at the checkout counter. By one estimation, food production in the U.S. actually costs society three times more than we purchase. One could argue that we would all be better off paying twice as much for food grown in a regenerative paradigm. That would represent a 33 percent net savings to society.

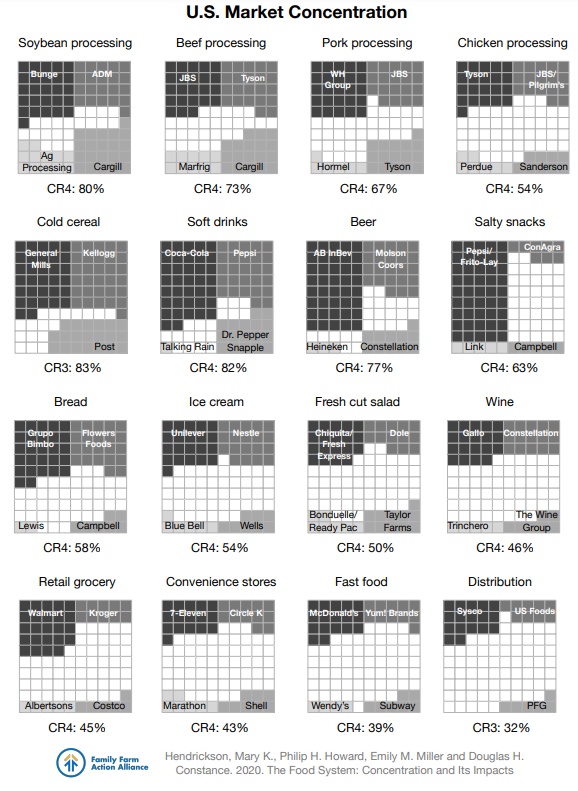

Second, we need to address the bottleneck in the food system: the barbell-shaped supply chain. Hundreds of thousands of farmers and millions of consumers primarily interact through a handful of food companies. These food companies effectively operate as oligopolies with tremendous leverage on prices, quality, crop selection and policy.

This leads to the third issue: diversity, which is a keystone of natural systems. Nature abhors “sameness” and is always endeavoring to establish diversity. But we have taken a beautifully diverse natural system, used technology to try and conquer that diversity, packaged it up with market-distorting policies, consolidated and homogenized everything for the sake of efficiency and productivity, and have lost much of our resiliency as a result. The frailty of our food system, along with other highly concentrated industries, became glaringly exposed during the most recent health pandemic.

Most of the regenerative focus has rightfully been on agricultural production as the starting point. This needs to expand rapidly into the policy realm, financial systems, healthcare, and the processing, distribution and marketing domains. We can wishfully think that market forces will eventually drive the necessary changes, but we really can’t wait one or two generations for these changes to occur. Scarce resources — healthy soil, biodiversity, clean water, human health, livable climate — are all being consumed or destroyed at an unsustainable pace.

The job of the regenerative movement is to demonstrate the art of the possible, even against seemingly impossible odds. There are many points of light out there — people who are showing us the better way agronomically, ecologically, socially, economically, politically and structurally. Unfortunately, some folks already seem to have found their way to the boxing ring, and the main attraction is karma vs. dogma. This shows up most visibly in the labeling and certification arenas, where some folks just can’t stand a lack of rules and definitions. It’s a waste of time and energy to get stuck on this, in my opinion.

That’s not to say that measuring outcomes is not important. Quite the opposite, as numbers can convey simple yet meaningful information. We need true and complete information about economic and ecological outcomes. What is working and what isn’t. We need more research and data about crop quality and human health outcomes. But rather than waiting for perfection and allowing that to be the enemy of continuous improvement, we already know directionally which way to go. There’s work to be done, onward and upward!

Technology is often referred to as the silver bullet to extract us from the current downward trajectory, especially in food and agriculture. Technological advancement often means winners and losers, as we replace things that exist with new things. Man grew up as child of Mother Nature, and technology is our way of trying to break free from her grip and liberating our future. But in the case of the complex food system, we are trying to cut the Gordian knot rather than truly understanding that we are intractably bound to natural systems. Not that technology doesn’t have a role to play here, especially in the fields of testing and research. But we seem collectively stuck, always trying to develop adversarial technologies in food and agriculture rather than complementary technologies that support and protect natural systems. Imagine the forsaken possibilities of coupling human intellect with natural wisdom.

Much of our focus has been diverted to “feed the world” — the battle cry of the Green Revolution and the red herring darling of the agro-industrial complex. Unfortunately, a lot of good people still follow this pied piper. If feeding the world was truly the goal, we would be doing a lot more work to establish and defend local food production systems, both here and abroad. That’s not to exclude international trade as a supplement to countries getting up to speed and as necessary for certain economies to maintain economic stability. But we have intentionally created foreign dependencies on U.S. agricultural production because of our unobstructed ability to overproduce in the short term. Our agricultural exceptionalism has had grave consequences, intended or not, across the developing world.

Reintroducing local and regional food systems in the U.S. is often scoffed as being inefficient and potentially costly. When seen through the subsidized and protected lens of conventional agriculture, that is probably true. When viewed through a regenerative lens, however, these local food systems are critical. For instance, if reintegrating animal production as part of a healthy and diverse agricultural ecosystem is going to be possible, we need dozens of mid-sized, locally owned processors in strategic locations around the country. Today, 85 percent of the beef slaughtered in the U.S. is performed by just four companies, the largest of which is foreign owned. The top three chicken companies control over 50 percent of the market; the top two pork companies control over 40 percent, and 65 percent of that is foreign owned. These effective monopolies dictate the terms of trade, push down fair wages, push up prices illegally and rake in record profits … that they then use to defend the status quo — another form of agricultural exceptionalism, this time in the form of excluding these industries from antitrust regulations.

The same concept holds true for seedstock. The seed industry has consolidated magnificently over the last 30 years. The top four firms now control over 60 percent of global seed sales, and three of them are foreign owned. By 2008, Monsanto’s (now part of the Bayer portfolio) patented genetics alone were planted on 80 percent of U.S. corn acres, 86 percent of cotton acres and 92 percent of soybean acres. Today, these percentages are even higher. As with the meat industry, this means that they get to dictate the terms of trade, set prices, hammer farmers with lawsuits and generally decide what American (and global) farmers can plant. This single industry — along with their co-owned ag chemical businesses — are mostly responsible for the biodiversity collapse across global ecosystems.

And on and on … across soybean processing, beer, cereal, retail, food service and more. And not mentioned here is similar consolidation in the petroleum, ethanol, fertilizer and ag equipment sectors.

Why is all this important and relevant to the regenerative movement? Freedom to operate is the primary issue at stake. Conventional farmers are stuck in the interstices between these enormous forces. Those who want to try something new have to navigate the reality that those in power may not like it, certainly don’t want it, won’t pay you for your good work and will fight you at every chance to preserve their market power. You also run a serious risk of falling outside of the rules the federal government safety net.

Is there any good news? Well, maybe. Let’s start with the stakeholders of the regenerative movement: farmers and their families, landowners, rural communities, urban communities, input providers, off-takers of farm production, processors, food companies, consumers, culinary groups, ecological systems, healthcare organizations, financial institutions, insurance companies, logistics providers, every government agency at every level of government, advisors and consultants, NGOs and other non-profits, colleges and universities, all 50 states … I’m sure I have missed several. Point being, every living thing and organization on Earth interacts with the food system every single day. We all have much in common when it comes to food.

Unlikely coalitions need to be formed where common ground creates multilateral benefits. A favorite dream of mine has to do with the agricultural land around population centers. Maybe 50 miles around the Twin Cities, maybe 20 miles around Des Moines, etc. This is my First Ring dream. As many of those acres as possible should be producing food — lots of different kinds of foods. Foods that honor the traditions of the local populations. Healthier food with fewer food miles. Highly diverse farming systems that honor the natural order of things — precisely the opposite of the conventional system. Integrated processing and manufacturing. People of many backgrounds and traditions working collaboratively, sharing resources and caring for resources because they have a stake in the system.

Who would need to be at the table in this utopian scheme? Landowners and farmers for starters. Experienced farmers and those new to farming to build the bench for the next generation. State, county and city governments, either to remove roadblocks and/or create enabling programs. The food service sector, hospitals, educational institutions. Community kitchens and culinary wizards. Processors and distributors. Financial institutions and health insurance groups. Water authorities and utility companies. Maybe even legacy food companies if they are sincere about contributing to, and not extracting from, this coalition. Labor, both skilled and learning — somebody has to break a sweat and do the real work.

Climate and soil structures will dictate what is possible and where, which is much broader than you might imagine today looking out over fields of corn, soybeans and wheat. Bananas are being grown in Vancouver today. Heck, we grew tobacco in Minnesota from 1860 to 1940. If you look back through various historical almanacs, you will find dozens of crops grown all over the country. I’m suggesting we concentrate that concept (minus the tobacco) into these First Ring areas, at least initially. How far it expands will be determined over time. No two locations will be exactly the same, but the model of collaboration should prove portable.

This is doable immediately. No need to wait for electric vehicles to downsize the demand for corn ethanol, although that is certainly on the horizon. No need to wait for a majority of rural water sources to either dry up or become too polluted to use, although we are already there in many locations across the country. No need to wait for federal policies to change, although we are on the doorstep of the next Farm Bill where hopefully we can make some meaningful progress. No need to wait for an academic study or a perfect model coming out of some think tank. This is building the airplane while we are flying it.

That’s my regenerative dream — my dream for a new kind of agricultural exceptionalism in America.