If we would just address its underlying issues — by applying the principles of soil health — water quality degradation would not be a problem

Poor water quality from nonpoint agricultural pollution is considered a “wicked” problem. Conflicting social, political, economic and environmental factors prevent easy solutions. However, the reason we have been unable to tackle water quality problems is because government programs and industry initiatives focus on treating the symptoms (e.g. sediment loading, nutrient loss) rather than addressing the underlying cause of the problem.

The root cause of degraded water is dysfunctional soil. Soil that is dysfunctional cannot infiltrate water or cycle nutrients effectively. Most agricultural soils have poor biological activity, resulting in broken carbon and water cycles. This is primarily due to lack of diverse living ground cover and surface armor, excessive physical and chemical disturbance, and nutrient management practices that do not account for the fact that soil is a biological system.

Relying on taxpayer funding to subsidize practices that treat pollution after it leaves the field will never seriously address water quality problems, and attempting to do so is a waste of time and money. Promoting these practices to the public as a “solution” to ag water quality problems is just greenwashing. Funding should instead go toward practices that address soil dysfunction in the field, where the problem starts, and education on how to implement those successfully. It is the only scalable and affordable solution.

Everyone involved in agriculture must understand soil function and ecosystem processes. Soil stewardship training should be required in order to access government funding. This would be a far better use of taxpayer money than any other farm program. The people managing our land hold everyone’s future in their hands. There should be some minimal expectations for soil stewardship in exchange for taxpayer support.

A 6P Approach to Nutrient Management

Current nutrient management initiatives mostly focus on the “4R” strategy — the right rate, source, place and time for applying nutrients. It is well-intended, but the 4Rs are voluntary, and there is no definitive definition of what “right” is. Research on implementing 4R practices shows that they have very little effect on improving water quality. This is because the 4Rs by themselves do not address soil dysfunction.

For that we need a different strategy — a 6P strategy, as in the six principles of soil health. Implementing the soil health principles should be priority one for all of agriculture, not just lip service.

The principles work because they allow plants to work with the microbial community in the soil to build aggregates as nature intended. Soil needs to be well aggregated so it can breathe and infiltrate water or it will not effectively cycle nutrients. It does not function properly without an intact soil food web. Mycorrhizal fungi are the lynchpin of good soil function, and they are lacking in most agricultural soils due to excessive physical and chemical disturbance. Simply having adequate fungal colonization of plant roots would vastly improve nutrient use efficiency, add organic matter, help fix broken water cycles, and give us cleaner water.

The role that good soil function plays for nutrient stewardship cannot be overstated. It is impossible to eliminate nutrient and sediment loss from bare soil. We must keep living roots in the soil year-round, minimize disturbance, maximize soil armor, add diversity to our crop fields, and better integrate livestock into the landscape.

We must also embrace the fact that soil is a living ecosystem and needs to be managed accordingly. Herbicides and pesticides are harmful to soil, plant, animal and human health and should be the last line of defense, not the first tool we reach for. More biologically friendly herbicides, combined with sound agronomic management and a bit of technology, can address weed control challenges. Pesticides can be phased out over time by focusing efforts on growing healthy plants with a strong immune system.

Let the 6Ps Guide What Is “Right”

The fastest way to diminish the soil’s ability to supply nutrients naturally is to apply high doses of readily available nutrients. This shuts down the activity of organisms in the soil that can do the job for free. The soil has a living digestive system and needs to be fed accordingly. It cannot properly digest months’ or years’ worth of nutrients applied all at once. This creates imbalances and nutrient antagonisms and leads to nutrient loss. High-salt fertilizers add insult to injury by inhibiting soil biology and creating osmotic stress in plants. There is no right time to apply too much of any nutrient.

To dial in application rates, every farm needs zero-fertility-rate trials to determine if or how much additional fertility is needed. Yield should never be pursued in isolation from nutrient use efficiency. Applying nutrients because that’s what the textbook says to do, or “just in case,” is contributing to polluted drinking water and large aquatic dead zones around the world. It is a recipe for disaster for all of us. Implementing the soil health principles and letting nature cycle nutrients and make some nitrogen for us is a much safer, healthier and more profitable way forward.

Determining the right timing for a nutrient application can be tricky, but it is rarely months before the plant needs it. Fall application of nutrients for a cash crop the following year makes no sense from a plant nutrition standpoint. It is a recipe for nitrogen loss, especially if the soil is bare. Nitrogen should be split applied and put on in small amounts at planting and as a sidedress or foliar spray.

Fall tillage and fertility applications are common because “There’s not enough time to do it in the spring.” Fall cover crop establishment is uncommon because “There’s not enough time to do it in the fall.” This is backwards. Establishing a cover crop should be priority one in the fall. Use living roots for bio-tillage and soil stabilization and put down nutrients at planting and in-season when plants need them.

Living ground cover is especially critical on acres receiving manure from confinement operations. This is hands-down the best, most profitable use case for cover crops. This is low-hanging fruit, and most of it is not being picked. Livestock industry groups should make it clear to members that cover crops and more in-season application must become part of all manure management programs. Voluntary actions like this would go a long way toward addressing soil and water degradation and rebuilding public trust in agriculture.

Tackling Nitrate Leaching

It’s said that our cropping systems in the Midwest are “leaky” and that nitrate leaching is unavoidable. This is false. The problem is not our soil; it’s how we manage it. Properly functioning soil does not lose nutrients — it recycles them. In healthy soil, biological activity makes small amounts of nitrate available to the plant as needed, which is quickly used, before it leaches away. Farming in a way that relies on organic nitrogen and biological activity rather than overloading the soil with nitrate will minimize leaching. Tile drainage complicates water quality efforts, but this can be mitigated with biologically based farming practices.

Think of nitrate as the problem child of nitrogen forms. It is readily taken up by plants, but it is highly soluble in water and does not stick to clay particles, making it highly prone to leaching. Excess nitrate in soil water can interfere with the uptake of other anions and cause plant stress. Nitrate can also wreak havoc inside the plant if it does not have the other minerals and energy it needs to convert it to amino acids.

Nitrate buildup in the plant is like a flashing neon sign for insects, saying “I’m sick, come and eat me.” This leads to a downward spiral of poor plant health and pesticide use. Apply a pesticide –> kill beneficial biology –> weaken the plant’s immune system –> sicker plants –> pathogen attack –> apply more pesticide. Improving nitrogen management would reduce our reliance on pesticides, and the entire system would function better.

Table 1. Sources of nitrogen available for plant uptake.

| Nitrogen Form | Efficiency of Uptake |

|---|---|

| Nitrate | Less efficient |

| Ammonium | Most efficient |

| Urea | Most efficient |

| Amino Acids/Amino Sugars | Most efficient |

| Living Microbes | Most efficient |

To improve N use efficiency and reduce leaching, we can apply amino acid forms of nitrogen like fish hydrolysate, algae or seaweed products. These organic sources of nitrogen are very efficient and supply energy to the plant, rather than using energy and water, as is the case with nitrate. Organic forms of nitrogen do not inhibit soil biology and do not leach or volatilize. They stay in the soil and cycle through the soil food web.

Inorganic nitrogen fertilizers should be applied with a source of carbon. This is a simple way to reduce nitrate leaching and the amount of N applied. Humic products are natural carbon-based nutrient stabilizers that enhance soil and plant health and should be considered for all fertility, manure management and herbicide programs. It’s critical to keep in mind that it’s not just a matter of stabilizing nitrogen or applying it in organic forms. We need good soil aggregation and biological activity in order for organic nitrogen to be used by the plant.

The Solution to Water Quality Woes

You may have noticed “living microbes” in Table 1. It’s true — plants attract and ingest microbes through the root tip and strip off their cell wall for nutrition. This process is called the rhizophagy cycle. The incredible work Dr. James White and others have done in recent years to understand this process has completely revolutionized everything we thought we knew about how plants access nutrients.

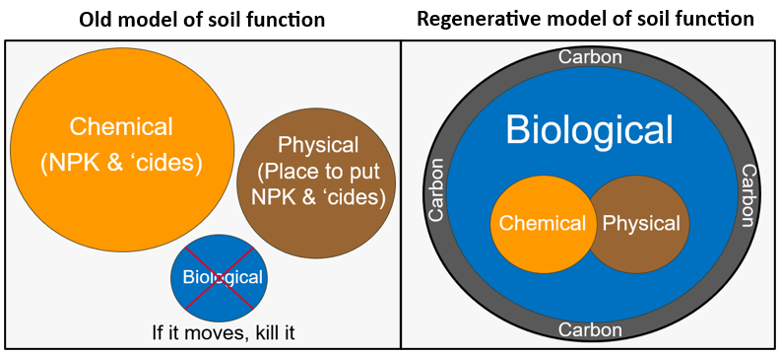

The old model of nutrient acquisition assumes that plants mainly access nutrients by taking them up from soil solution, but this is only true in dysfunctional soil. It is a very incomplete way of understanding nutrient cycling, and it leads to poor fertility management decisions that degrade the environment.

The “right” source of fertility is not fertilizer at all — it is soil organisms. The fertilizer truck should not be feeding nutrients directly to your plants. That job belongs entirely to soil organisms, and we need to let them do it. This relatively simple change, accomplished by integrating the 6Ps and refocusing our management to nurture life in the soil, would radically transform agriculture for the better and deal with the root cause of dysfunctional soil and poor water quality.

The old model of soil function is dead, and we need to bury it. We cannot use simple formulas to determine nutrient application rates. Farming in a way that ignores or actively inhibits biological nutrient cycling is the primary cause of soil and water quality degradation. Education and research should begin and end with the fundamental premise that biological farming systems are the only sustainable way to feed the world because soil, plant, animal and human health are inseparable. When we harm biology in the soil, we harm everything, and we eat, drink and live with the polluted results.

Critics of this approach will argue that it would require too much labor and too many acres to grow cover crop seed. These are features, not bugs. A more regenerative approach would create a market for desperately needed alternative crops and reduce our reliance on low-value commodity crops for revenue — not to mention all of the benefits to ecosystem health. It would open up opportunities to grow diverse, N-fixing summer cover crop mixes that could be grazed by livestock. It also creates an entirely new industry built around regenerating the soil that would provide good jobs in rural areas and opportunities for young people to get involved in agriculture.

It’s also said that high-input, high-yield agriculture is the only way we can feed the world. This is nonsense. Diverse, regeneratively managed farms and ranches often outproduce their conventional counterparts on a total calories per acre basis, and that food is typically higher in nutritional quality. We most certainly will not continue feeding the world with our current input-and-energy-intensive system that allows our soil to erode away to grow low-value commodities that are only profitable with government support. We’ve been chasing more bushels for decades, and it has hollowed out the heart of rural America. We need a system that rewards the farmer, regenerates soil, revitalizes rural communities, produces healthy food and addresses the underlying cause of soil and water quality degradation. We need to drill baby, drill — with cover crops.

The only way to address agricultural water quality problems at scale is with a biological approach to land management. If we work together to implement the soil health principles, states will have no problem exceeding their nutrient reduction strategy goals. We know how to do it, and we owe it to ourselves and future generations to act now.

It’s time for the agricultural community to come together and show that we really are the best stewards of the land. The sooner we focus on implementing the 6P strategy to make our soils healthier and better functioning, the sooner we can improve our water, our profits, our health and our future.

Brian Dougherty is a farmer and a consultant with Understanding Ag. He is a former Nuffield Scholar and Iowa extension agent. He will be a speaker at this year’s Acres U.S.A. Eco-Ag Conference: conference.eco-ag.com.