Why and how to apply for a farmer-led research grant

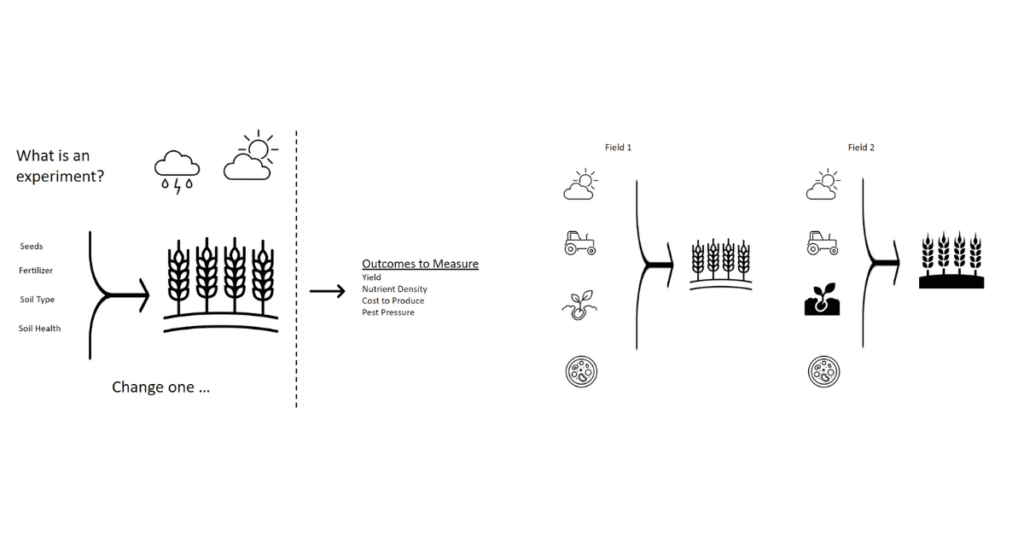

Growing food is an experiment. Even if you grow exactly the same crops each year, the weather varies. If one variable changes while the rest remain constant, that’s an experiment.

But who does the same thing each year? You trial new tomato varieties, swap oats for millet in a couple of fields, or test out different seed treatments for your flowers. You’re constantly looking for things that will improve your yields, shelf life, protein levels, ease of cultivation and harvest.

Most of these trials are applicable to your space, your growing practices and your crops. They’re fodder for conversations with other farmers, but not something that could be replicated on another farm. But every so often you test things that have a broader application — and when you do, there’s a chance you can get some money to help offset the costs of the experiment.

How do you know whether your experiments have broader applicability? Look for processes you can document and outcomes you can measure. The biggest difference between an informal test and something that you can get funded is whether you can provide enough information for someone else to try the same thing elsewhere. And a lot of that comes down to your knowledge of your farm, your ability to collect data and your ability to design the experiment.

Let’s break each of those factors down in the context of getting funding for your experiments.

Know Your Farm

This is basic — you know where your farm is, your average rainfall, soil type, etc. In the context of getting funding, your farm’s situation matters because the more descriptive you can be, the better other farmers are able to judge how your results might apply to them, and how they might need to adjust your methodologies in their situations.

Say you’re a grain farmer in Arizona; your experimentation with biological seed treatments could be relevant to other grain growers, but they’ll want to know your soil type, rainfall patterns, any irrigation protocols, application rates, field prep practices, etc. Think about what you would ask if you were talking to another farmer at a conference about something they had tried on their farm. Those are the details you should include as part of your proposal to get experimental funding.

Collect the Data

This is another basic concept, and yet it’s one of the hardest things to manage, because when the broccoli needs harvesting, the cows have gotten out, and the hay has to come in, the logical decision is to skip collecting data and finish the thing that makes you money. Except when you’re getting paid to run an experiment, that data is one of the things that makes you money.

Think back through tests you’ve run on your farm over the past few years. How many of them ended with a gut feel? It was faster to feed this way instead of that way. How much faster? Using that seed treatment took longer, but it paid off at harvest time. How much longer, and how big was the payoff? Get in the habit of thinking in numbers instead of gut checks — you’ll need the skill for research grants, and it’ll benefit your farm as a whole. (Why it will benefit your farm could be a whole other article but suffice it to say that gut checks can be either spot on or horribly inaccurate.)

Design the Experiment

How do you gather the data, and what data should you gather? That’s all part of experimental design.

State the question — is it something that other farmers might be interested in knowing? Have other people done this work, perhaps in other climates? In general, you’re not likely to get funding for something that’s already been done in your region, or that is widely accepted already. You won’t get funding to buy compost to put on your land, or to buy a roller crimper and seed drill so you can test out cover crops. But you might get funding to test the effects of adding inoculating compost to a cover crop planting in your bioregion, assuming you structure your experiment correctly.

Identify the variables — what factors could impact the outcome of the project, and how can you identify their impact? I mentioned earlier that the weather is always a variable from year to year, but also consider your landscape and the influences on it. Are some fields wetter than others? Do you have a neighbor on one side who uses dicamba or glyphosate? Do the predominant winds change throughout the course of the year, or do various fields have windbreaks while others don’t? You’re looking for things you can’t change and will have to design around to ensure that your results are applicable to others off your farm.

How can you control variables? When I say control, I mean structure your experiment in such a way that the variables happen universally. You can’t control the weather, but you can set up your inoculated compost cover crop stand next to a non-inoculated stand so that the weather happens equally to each one.

Let’s say you want to compare the effects of side dressing with inoculant compost to spraying with compost tea in field tomato production. You’d want to have the treated tomatoes in the same field, or adjacent fields, to minimize the difference in soil, wind, rain and temperature exposure. You’d want to have the different treatment groups kept under the same irrigation and soil prep schedules so they’re all getting the same base of water and nutrients. And you’ll want to have a control group — a space where you treat the tomatoes how you would normally so that you have those results to compare to the different treatments

Measuring What Matters

I once consulted for a farming nonprofit on their data collection, and the executive director was quite insistent that we needed to be capturing every data point. Finally I told her, “I could log the number of trips to the bathroom you take each day, but it wouldn’t get us any closer to our mission.”

When it comes to collecting data on your own experiments, the same rule applies. You could log air and soil temperatures on an hourly basis in your fields, but would it improve your understanding of what’s happening with your experiment? Think about what you would ask if you had heard of another farmer doing what you’re proposing — what data would help you decide whether to try it yourself?

Generally, you’ll want to record measurements on the outcomes you’re expecting to see — think yield, days to harvest, and maybe disease or pest pressure. If you’re expecting to see changes in your soil biodiversity, you’ll want to measure that with regular microscope analysis, MicroBiometer measurements or Haney tests. If you use soil amendments or take soil tests prior to running your experiments, you’ll want to keep those records so you and others understand the baseline.

Statistical Significance

This article is not the space to get into the intricacies of statistical significance, but it’s also not something you can completely ignore in designing your experiment. Statistical significance is what people point to when trying to understand whether the changes you make between the groups in your experiment are responsible for the outcomes you measure at the end or are just due to chance.

No one is expecting farmer-led research to tick all the boxes for statistical significance, and that’s part of the point — as farmers, we’re working with these ideas in our own spaces, and funding for research isn’t going to replace the other income from your farm. What this translates to in terms of your experimental design is that you’ll want to design your experiment to address whether your conclusions could be the result of chance, but with the understanding that there’s no practical way for you as a farmer to address every possible factor that could influence your results.

To put it in the simplest terms, run your experiment multiple times. Instead of setting aside three rows — one each to test your compost, compost tea and control groups — set aside nine or 12 rows so that you can repeat each test three to four times. You’ll want to make sure you have at least 25 plants in each row, so that your results from each section will be based on multiple plants. Change up the order of your rows so you don’t have all your compost rows in one block. This means that if you get pesticide drift from one direction, or a prevailing wind or micro hail storm, you don’t run the risk of losing an entire experimental group.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflict of interest can come in on occasion, especially if you’re running a particularly expensive project. Think about yourself as a skeptical farmer hearing your results. What would lead you to question your integrity? Often it’s the things we have blind spots about. For example, I work with AEA consultants on my own farm and am also enrolled in Elaine Ingham’s Soil Consultant Program. My own experience leads me to think that the answer to building resilient soil ecosystems while also remaining profitable lies somewhere between the two methodologies. So, when I applied for funding to study different combinations of the two, I figured it was obvious that I wasn’t an acolyte of one or the other. I lost the funding because the committee assumed my consultant training would bias me toward the Soil Food Web techniques.

When designing your experiment, take a hard look at your own affiliations. If there are potential conflicts, how can you address those? In my case, I could have suggested someone else serve as the primary investigator and put myself in a position where I wasn’t managing the day to day of the project — it would have been less fun for me, but better for the project as a whole.

When (And Where) to Get Help and Funding

Experimental designs tend to emerge best when they’re tossed around between multiple people. Talk to farmers in your area who have gotten funding for farmer-led experiments before. Talk to your extension agent, the agronomists you work with, or researchers at your local university. Drop me an email — I love to talk through research ideas, and my company can help with grant writing at no upfront cost to you.

The most accessible funding for farmer-led research is Sustainable Agriculture and Education (sare.org). They offer farmer research and producer grants across the U.S. with funds ranging from $20,000 to $30,000 over a two-year period.

On the federal level, NRCS Conservation Innovation Grants offer a larger funding pool, but also a larger pool of applicants that often includes universities. This is definitely a grant to pursue with a coalition — find someone from extension or a researcher from a company or university to work with you and to lend some name recognition to your application.

If you’re pursing ideas that are completely unique and have commercial potential, check out the Small Business Innovation Research program, which can provide funding for technology or product development to small businesses.

Cultivate relationships with your local land-grant university professors, especially those who research what you grow. They have to pursue funding for their own work, and they may be able to work with you to run some of the experiments you have in mind, especially if it fits with what they’re already pursuing.

If your land is certified organic, the Organic Farming Research Foundation (ofrf.org) and the Organic Crop Improvement Association (ocia.org) have grant programs to support research related to organic production.

In conclusion, it’s possible to get funding for something you’re likely already doing —experimenting. You won’t get enough to replace your farm income, but with some thought as to how you structure your experiments you can both cover the costs and add to the bank of knowledge we’re all building as farmers.

Kirsten Simmons is the co-founder and Chief Farming Officer for Good Agriculture (goodagriculture.com), a company dedicated to helping farmers find funding, manage finances, reach new customers and get certified. She also farms at Ecosystem Farm (ecosystemfarm.com), the only u-pick strawberry farm inside Atlanta.