Making a living with crop specialization: strategies for farmer resilience

This month’s strand in the farmer safety net is a bit counterintuitive. I’d like to talk about crop specialization. How many crops do you grow? One? Five? Twenty-five? Fifty? And if we drill into just one of those crops — say lettuce — how many varieties do you grow throughout the year? Ten?

Each variety of every crop you grow increases the complexity of your business. And complexity can be a double-edged sword. Some complexity is a benefit to a business — there is logic to diversifying your income streams and hedging your bets with various crops or varieties such that if one fails, you don’t lose your shirt.

That said, the diversified vegetable model is not sustainable. Yes, there are a few people who do it well, but I’d wager that a close audit of their production costs would find more than a few crops that lose money — or that their enterprises are helped significantly by income from teaching others about what they do.

My definition of a successful farmer is someone who makes a living wage from their farm, has a plan for retirement, pays their crew fairly, doesn’t destroy the surrounding environment, and works a sustainable number of hours per week. I have yet to see anyone do that successfully without specializing.

Multiple crops increase complexity. Each crop has different growth preferences, and each variety of every crop will have differences that ought to be taken into account to allow you to optimize the yield of each variety. Increasing complexity, especially when you’re just starting out, is a recipe for failure. And it’s hard to learn from the successes you do have because you’re going in 15 directions at once and don’t have the time to sit down and think through what’s working and why. Start with one crop. Figure out how to do it well. Once you’re producing one crop well, diversify either your crop OR your customers.

Let’s talk about diversifying your crop first. The instinct is to go for something completely different that can do well if weather or other factors cause your first crop to fail. If you can do this without investing in additional infrastructure, it’s worth trying. That said, if it’s going to cost you to get started, it’s not worth the extra complexity. Instead, go for a similar crop to what you’re already growing. If you’ve learned to grow amazing cherry tomatoes, figured out season extension and have a few varieties in your fields, or maybe try a crop of determinant romas that you can sell for sauce. Maybe add a pepper or squash that thrives in similar temperatures to your tomatoes. Don’t start growing something completely different like greens or carrots.

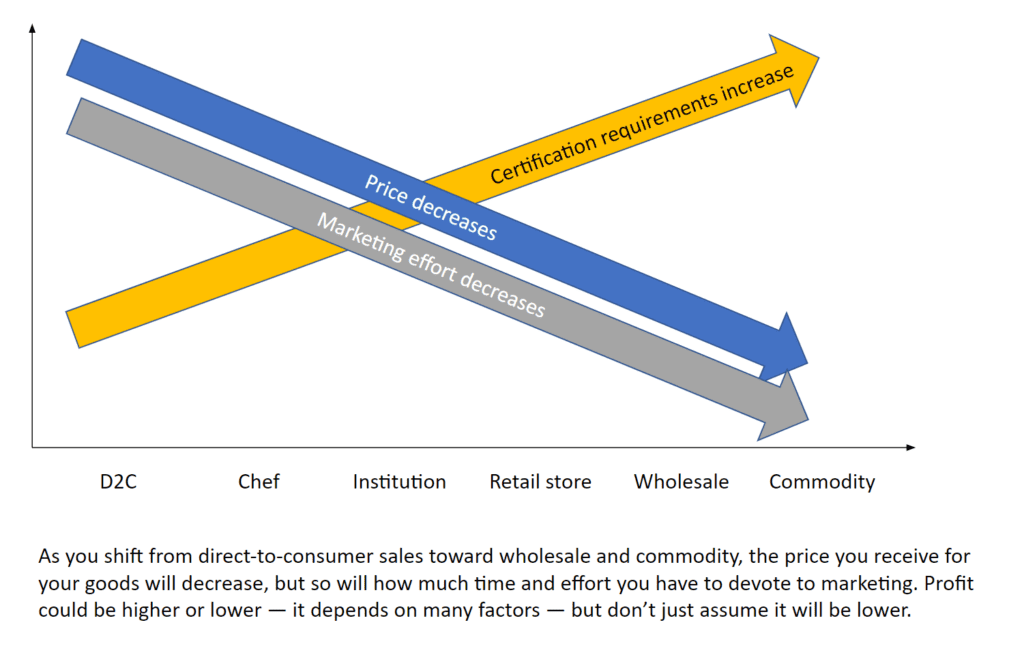

Potentially even more powerful than crop diversity is customer diversity. You already grow amazing cherry tomatoes, but you’re growing too many to sell direct-to-consumer. There are only so many farmers markets you can attend in a week, and only so many people able to pay $5/pint. Can you ramp up your production enough to sell to the local grocery store? How about the elementary school or hospital? You won’t get as much per pound in these markets, but you’ll be able to sell a lot more. And you’ll be dropping that volume in fewer places. That’s not to say that you should give up direct-to-consumer, but that by selling along a spectrum between consumer and institution, you’ll be able to make your business more resilient.

The other plus of diversifying your customers to move larger volumes is that your time required to sell per unit will go down. Think about selling at a farmers market — how many times have you seen perfectly good produce go unsold because it’s not wrapped up in a perfect package, or because your market staff didn’t come to work with their sales hustle on? Selling direct to consumer is high margin, high intensity and low volume.

Southern Swiss Dairy in Georgia is a great example of deliberate product and customer diversification. They had sold to the milk co-op for years, and when dairy prices dropped in the early 2000s they were faced with losing the farm. Rather than folding or shifting to another crop entirely, they opted to add a bottling plant and to begin selling direct-to-consumer under their own brand. Then they added butter and ice cream and began to sell to local stores and distributors, while keeping the direct sales.

Today you can order directly from their website for delivery or purchase their products at 20-plus stores across Georgia, ranging from local groceries to a few Whole Foods locations. They have a much more resilient business with three products and a variety of customers than they did with a single product and a single customer.

I do often hear one objection to this strand of the farmer safety net: what if I don’t want to produce at a volume where I can realistically sell to larger accounts? That’s your choice to make. Selling in larger volumes requires attention to systems that allow you to grow your product efficiently. For fruit and vegetable farmers, it may require attention to food safety that you wouldn’t have to address as a tiny, direct-to-consumer operation. If those aren’t steps you want to take, you can use other strands of the farmer safety net to build a resilient business and become a successful farmer.

Kirsten Simmons is the co-founder and Chief Farming Officer for Good Agriculture (goodagriculture.com), a company dedicated to helping farmers find funding, manage finances, reach new customers and get certified. She also farms at Ecosystem Farm (ecosystemfarm.com), the only u-pick strawberry farm inside Atlanta.