Making Farms Complex Again

Rotating crops, conserving soil nutrients and deploying other strategies to diversify agriculture all at the same time can yield major benefits for the environment and people alike — including increased crop yields and improved food security for entire communities.

That’s the take-home message of a landmark new study, including researchers from more than 15 nations and data from 2,655 farms on five continents. The team published its findings April 4 in the journal Science.

“This is evidence that this can actually work — we can imagine agricultural systems that are more diverse and serve people and nature at the same time,” said Zia Mehrabi, a co-author of the new study and assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado Boulder.

The study comes as farms across much of the world are increasingly growing just one type of crop or raising a single kind of animal — monoculture agriculture that may bring with it a wide range of risks, including the loss of soil nutrients and spreading pest outbreaks. In the United States, the number of farms in the country in 2022 dwindled to its lowest level since before the start of the Civil War, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Those remaining farms have only gotten bigger and simpler.

Diversification encompasses a wide range of strategies. In some cases, farmers might rotate between seeding a field with corn one year, then beans the next and okra the year after. In others, they might plant cover crops to keep their soils from washing away in the off season or even encourage healthy populations of earthworms underground.

Previous studies have tended to assess these strategies individually, and have delivered mixed results. The Colorado team tried a different approach: they used a combination of participatory methods and statistical tools to dive into data from 24 study systems. Their results captured information on everything from massive strawberry operations in the United States to small maize fields in Malawi and palm orchards in Indonesia.

The group discovered that farmers and ranchers can achieve many more benefits if they employ several agricultural solutions in tandem, rather than just one at a time. The study reveals a new vision for food around the globe — one in which farms and pastures work less like factories for churning out calories and more like healthy natural ecosystems.

“The crazy thing is that the positive effect of adding multiple diversification practices is true across wildly different contexts,” Mehrabi said. “It works on industrial farms in the United States and in small-scale maize farms in Malawi.”

He and his colleagues acknowledge that finances can be a barrier to making the switch to diverse agriculture. Farmers might need to purchase one set of machines to harvest corn and a different set to harvest fruit.

But governments already spend huge sums to buffer the agricultural industry. Some nations, for example, subsidize farmers so that they can grow water-intensive crops in areas that don’t get a lot of rain. That money might be better spent in helping farmers diversify.

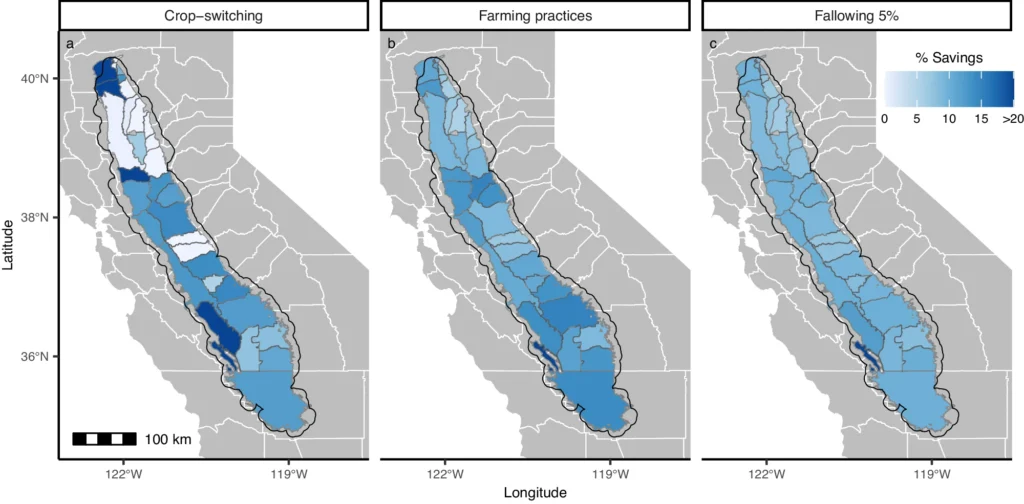

Three schema of switching crops, changing farming practices, and following fields all yielded average water savings of around 10 percent. (Courtesy of Boser et al.)

Small Changes Can Lead to Big Savings in Agricultural Water Use

With recent water challenges, some in California are beginning to even discuss legislation to forcibly take land out of agricultural production. Fortunately, a study out of UC Santa Barbara suggests less extreme measures could help address the state’s water issues. Researchers combined remote sensing, big data and machine learning to estimate how much water crops use in the state’s Central Valley. The results, published in Nature Communications, suggest that changing to more efficient practices could save as much water as switching crops or fallowing fields.

California’s fertile soils and Mediterranean climate enable farmers to cultivate high-value crops that just aren’t viable in the rest of the country. Over a third of the country’s vegetables, and nearly three-quarters of fruits and nuts, are grown in California, according to the state’s Department of Food and Agriculture.

But many of these crops are quite thirsty. Agriculture accounts for around 80 percent of water used in California.

Scientists have a variety of methods to estimate the amount of water ascending from the Earth’s surface to the atmosphere due to evaporation and transpiration through plant leaves. Notably, evaporation cools things down.

An evapotranspiration database called OpenET became publicly available in early 2023. It provides satellite-based evapotranspiration estimates for the western United States. Being interested in the water being used specifically by crops, the researchers compared transpiration in fallowed fields to active fields across the Central Valley. Subtracting evapotranspiration in fallow fields from total evapotranspiration yields the amount of water that crops are actually consuming.

Unfortunately, farmers don’t fallow fields randomly. They’ll often take their lowest-yielding fields out of production. That creates systematic differences between fallowed and cultivated fields, which could skew the analysis. So, the researchers created a machine-learning model to conduct a weighted comparison between active and fallowed land, accounting for factors like location, topography and soil quality.

They learned that crop type only explained 34 percent of the variation in water consumption. “What that means is maybe we’re overlooking some other ways that we could save water,” said lead author Anna Boser. She continued to investigate the model, controlling for factors like location, topography, local climate, soil quality and orchard age (when applicable). Ultimately, a full 10 percent of crop transpiration could be saved if the top 50 percent of water users reduced their water consumption to match that of their median-consuming neighbors. Boser attributes these savings to differences in “farming practices.”

Ten percent might not sound like a lot, but it’s comparable to a number of other interventions. The authors also estimated the effect of switching crops. If the same 50 percent of farmers switched to the median water-intensive crops for their area, agricultural evapotranspiration would drop by 10 percent.

Meanwhile, if the state took the top 5 percent most water-hungry fields out of production, the model says agricultural evapotranspiration would also drop by 10 percent. This suggests that addressing inefficiencies in farming practices could save as much water as switching crops or taking fields out of cultivation.

What practices are farmers using that account for the 10 percent differences in crop water usage? Some examples include mulching, no-till planting, using drought-tolerant varietals, and deficit irrigation.

Improving irrigation efficiency could also help. Inefficiencies include leakage, weed growth and evaporation in transport and in the field. These factors are actually quite poorly understood, according to Boser.

Better Phosphorus Use Can Ensure Stocks Last More Than 500 Years and Boost Global Food Production

More efficient use of phosphorus could see limited stocks of the important fertilizer last more than 500 years and boost global food production to feed growing populations. But these benefits will only happen if countries are less wasteful with how they use phosphorus, a study published in Nature Food shows.

Around 30-40 percent of farm soils have over-applications of phosphorus, with European and North American countries over-applying the most.

Listed as a critical raw material by the European Union, and recently a topic of discussion by the United Nations Environment Assembly, globally 20,500 kilotons of phosphorus are applied to agricultural soils each year as fertilizer.

Concerns have been raised about its limited supply and loss to freshwater, where it can degrade water quality. Phosphorus predominantly comes from mining phosphate rock, of which there are only a relatively small number of sources, located in countries like Morocco and Russia.

Previous estimates of how much phosphorus we have left globally have varied greatly from between 30 to over 300 years. These prior estimates were based on current wasteful practices continuing and contained a lot of uncertainty.

This latest research, looking at global phosphorus use and soil concentrations, examined concentrations of phosphorus in farm soils across the globe for optimum growth of 28 major food crops from wheat and maize to rice and apples. The research revealed soils that did not contain enough phosphorus and soils that contain concentrations higher than plants need for optimal growth.

The research team calculated that 10,556 kilotons of phosphorus are wasted each year through over-application, with much of that dominated by wheat and grassland in Europe and maize and rice in Asia.

Market Forces Provide Resilience to Climate and Food Security Challenges in Developed Countries

A study by the University of Southampton has found that market forces have provided good food price stability over the past half century, despite extreme weather conditions.

Research into U.S. wheat commodities by economists at Southampton also suggests that high uncertainty about the state of future harvests hasn’t destabilized the market.

The findings are published in the Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control.

Wheat is an important crop in the United States used for food production. A small fraction becomes animal feed, and the crop isn’t used to generate biofuel. The main buyers of wheat are flour mills, food processors, and direct consumers.

The researchers analyzed data on American wheat production, inventories, crop area, prices and wider market conditions from 1950 to 2018, together with records of annual fluctuations in the weather for the same period. This showed strong evidence of an increase in weather and harvest variability from 1974 onwards.

The authors found that in the U.S., the market system around wheat has remained competitive, functioning well and adapting to the new uncertain climate conditions. The potential for weather fluctuations to adversely affect wheat prices has increased, but this hasn’t been passed on to the market. Wheat prices remain relatively stable, along with the price of associated goods.

The researchers found that this is mainly due to farmers and agricultural industries providing a buffer, smoothing out any bumps in the supply of grain to retailers and consumers, thus reducing shocks to the market that poor harvests may cause. This has been achieved by investment in substantial storage facilities, modern infrastructure and good transport links.

According to the study, the U.S. wheat sector has demonstrated remarkable resilience and flexibility in adapting to the ever-increasing unpredictability of the climate and harvest by modifying its inventory management. At the same time, there is no indication that the wheat market is vulnerable to excessive volatility from the related financial futures market, which can often emerge in commodity markets in response to increased uncertainty regarding future production capacity.

Commenting on what policymakers can take from the research, Dr. Vincenzo De Lipsis of the University of Southampton said, “We have shown that market forces provide a powerful stabilizing mechanism to counter the increased variability in weather and harvest observed in the last half a century.

“The market mechanism is one of the most effective instruments that governments have available for climate change adaptation and food security. But for this to work effectively, we need a combination of factors in place: a well-functioning competitive commodity market, a modern infrastructure with extensive transport networks, sufficient food storage capacity and a liquid futures market.”

The authors acknowledge that stability is easier to achieve in developed and more affluent countries, but their results underscore the need to prioritize investment in these key areas in developing regions to ensure a reliable and secure food supply in the future.

| Organic Row Crop Research Any ecologically minded row crop farmer should take a look at the OGRAIN 2023 research report (geared toward the upper Midwest, but surely with applicability in other regions). The studies include the results of experiments and best practices for no-till organic soybeans, organic dry beans, reduced-tillage organic corn, organic oilseed crops and more. https://ograin.cals.wisc.edu/research |

| Ann Theresa Walters, 1929-2024 Ann Theresa Walters passed away peacefully on April 4, 2024, with family by her side, just three weeks shy of her 95th birthday.Ann was the youngest of six brothers and sisters growing up on the family dairy farm near Mount Pleasant, Michigan. Faith, love and hard work kept them whole through the Great Depression. She remembered her childhood as a happy one and kept close ties to Mount Pleasant throughout her life.After graduating from Sacred Heart Academy, she earned a Bachelor of Arts in English from Central Michigan University (then Central Michigan Normal School), a teacher’s college in her hometown, where she was also editor of the yearbook. While teaching high school English in Denver, Ann met Charles Walters Jr. at a Catholic singles mixer. Chuck (as friends and family called him), was a writer moonlighting that night as the event photographer. He was immediately struck by Ann’s charm and memorized her phone number. They fell in love and were married within a few months in 1956.Not long after marrying, Chuck and Ann moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where several members of his large Kansas farm family had settled after WWII. They raised four children: Christopher, Fred, Tim, and Jennifer, and lived in Raytown, Missouri for most of the 53 years they were married.Ann was a dedicated member of St. Bernadette Catholic Church. Her dedication and devotion to the Catholic faith served as a solid foundation and guide throughout her long life.Ann supported Chuck’s publishing pursuits and experienced the trials and joys of raising a growing family during those busy decades. When they Acres U.S.A. in 1971, Ann played an active role in the business. She put her English skills to work copyediting and proofreading the monthly magazine as well as many books and was a gracious presence at the magazine’s annual conference.A guest room at the Walters home was always available for people traveling through, be they exchange students, friends, relatives, or anyone from the family business’s network of contacts and collaborators from around the world.After Chuck passed away in 2009, Ann remained active until her health began to decline in 2022. Ann Theresa Walters leaves behind a legacy of love, laughter and unwavering dedication to those she held dear. She strived to always help others in little ways and felt it important to “keep the faith.” She will be deeply missed by her family, friends and all who were fortunate enough to know her. |