A popular concept was developed 40 years ago and has now reemerged

“Regenerative farming” is an increasingly popular expression, found widely in a range of farming media, agribusiness and climate forums, that serves as a catchphrase and a label for many practices, including “renewable,” “sustainable,” “ecological” and even “organic.”

The expression was first introduced by the organic farming community itself over 40 years ago when the Rodale organization sought to make organic more attractive in the mainstream. It emerged in a time of controversy, with the first tentative recognition in the U.S. of organic as a legitimate method of productive farming.

Recently, the label “regenerative” has also been used to denigrate, if not replace, organic, as in statements such as “now that we have regenerative, there is no need to use the word organic anymore.” Organizations and consultants promise better futures “beyond organic,” but with variable if not conflicting messages. An example of the broad stretch of new possibilities is seen in the new book What Your Food Ate by David Montgomery and Anne Biklé. A report by Dr. McQuire of Washington State University shows five prominent regenerative programs with very different components and warns about “extraordinary claims.” A new published paper from Colorado State University (Newton, et al., “What Is Regenerative Agriculture?”) points to emerging conflicts depending on whether process-based or outcome-based definitions for regenerative are adopted (organic methods are mostly considered process-based).

For those with an organic farming background, there is actually very little about regenerative practices that differs from those advocated over decades in organic and eco-farming. A good example is no-till, which is much touted as an alternative. Organic and traditional farming methods have always stressed crop rotations with pasturing and “ley” fields, which are essentially long-term grass-based no-till interspersed over time.

Conventional farming created the basic problem by reducing or removing true crop rotations to favor economic row crops. The emerging predicament meant that reduced tillage (and, additionally, intense cover cropping) became virtually the only alternative for soil restoration, mimicking the function of crop rotations. The entire modern concept of simplified plant-stand structure, with heavy reliance of herbicides — many of which were developed specifically to help no-till deal with weeds — has resulted in an overall biodiversity loss and depletion of ecosystem services.

Making the perfect the enemy of the good is usually a regrettable strategy. For clarity, to be better than (or even similar to) organic, “conventional regenerative” will at the very least have to explain eclectic practices (mixing chemical and organic treatments) and be prepared to establish a system of validation — as certified organic has — worldwide.

There are lessons from analogous events earlier in Europe, as pioneers of organic methods — referred to mostly as “biological” farming — first brought attention to the harsh impact of intensive chemical farming in the 1970s. This innovation and critique came from outside academia and unleashed many forms of opposition, yet it appears to have led to a different outcome. Certification and scientific comparisons were launched early, and soil health analytical methods were developed, and these were used to objectify comparisons, as in examples from the German Ministry of Agriculture (1977) and the Uppsala Agricultural College, Sweden, in 1979.

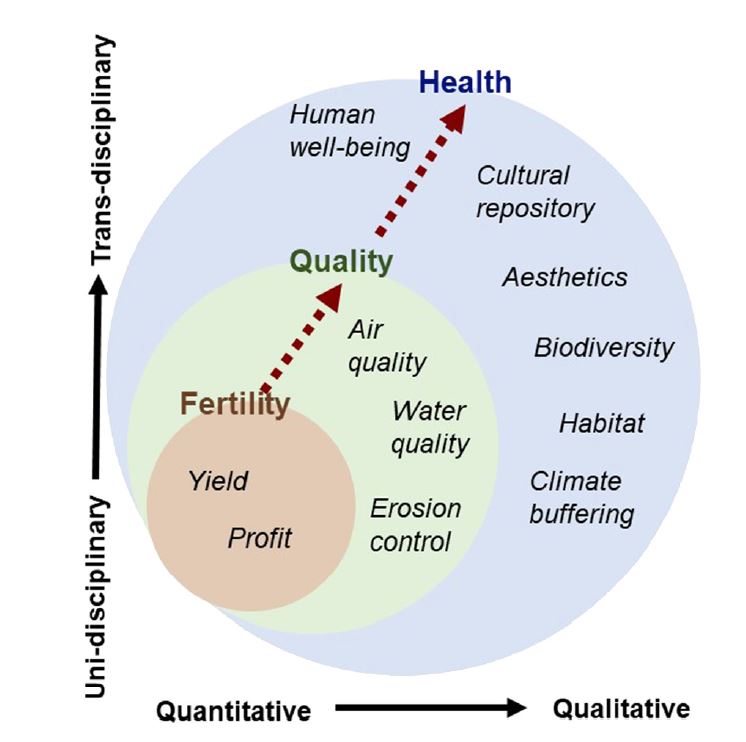

In the United States there was a brief exploration of “alternative” farming, which focused on soil quality. It was only after lengthy debate in the U.S. scientific community that this eventually turned into soil health. This was not before an entire USDA-NRCS division for soil health was set up and a coordinated private organization, the Soil Health Institute, was established — an effort clearly intended to control the narrative. A recent Canadian paper by Drs. Janzen and Gregorich raises questions concerning whether soil health is being treated in too reductionistic a manner by scientists, overlooking the goal of raising soil appreciation.

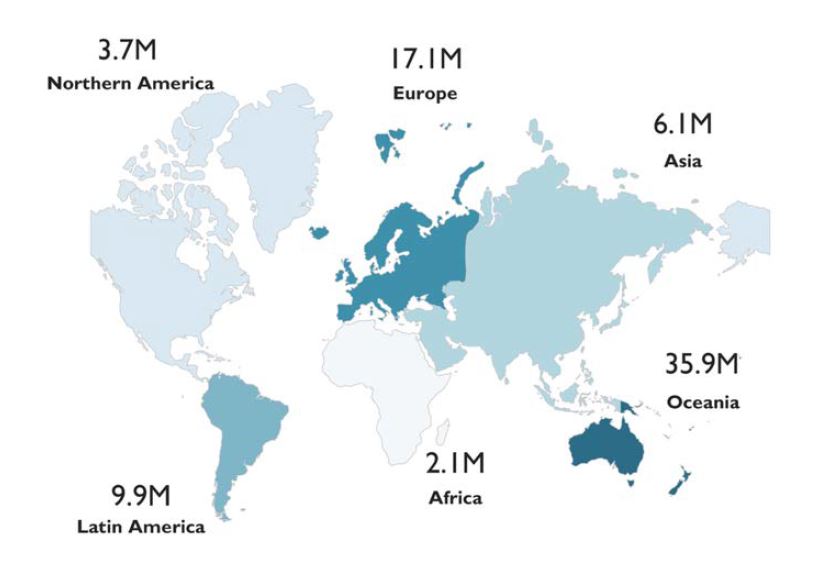

For those seeking to replace organic with regenerative, a sobering fact is the sheer scale of certified organic worldwide. Bio-farming certification programs exist that monitor the integrity of practices comprising a huge European land base of over 17 Mha (42 million acres), which is even larger than North America’s 3.7 Mha (9.2 million acres). This represents a large accomplishment over decades.

There is also strong scientific evidence, especially coming from Europe, for the technical superiority of organic when yields (which are lower than conventional) are counted with ecosystem services (which are significantly larger than conventional). The yield superiority favoring conventional that is often used as criticism of organic has been cracked open as more studies reveal that this “yield gap” is steadily narrowing. This apparent trend is supported by impressive spatial maps by workers at Oxford University, showing certified organic farming well dispersed across the globe with impressive footprints — from 5 to 26 percent of total agriculture land area (see Paull and Hennig’s “Atlas of Organics: Four Maps of the World of Organic Agriculture”). Surely regenerative would wish to complement and grow with this success rather than attempt to compete with or disrupt it.

Due to these growing concerns, studies critical of regenerative are raising doubts as to whether regenerative delivers on its many promises. The WSU study by McQuire disputes the soil carbon gains claimed for regenerative ranching methods in the northern great plains. In France, the regenerative vineyard programs offered as substitute for organic certification were tested in 300 vineyards, the result being that no significant quality improvements were observed, since the organic-certified wines scored statistically higher in professional taste tests than either regenerative or conventional. Having once weighed in heavily in the 1970s about merits to alternative biological farming, the Ministry of Agriculture in Württemberg recently investigated several new regenerative farms and found no gains in soil carbon after seven years, despite the claims.

In the U.S., with a seeming (and unnecessary) battleground forming between regenerative and organic, the strategic approach — taking the E.U. example — is that organic needs to grow its land share. Additionally, U.S. organic may have to confront its own failures and internal frictions, such as increasing opposition to USDA’s mishandling of organic certification processes, organic growers opposing their own Organic Trade Association politics, organic growers declining to be certified, and the many varying origin stories that can be confusing (see, for example, Paull’s biography of Lord Northbourne). These issues demand stronger unity of eco and organic growers, not more division due to a rivalry between regenerative and organic — which many feel only supports the agrichemical giants that may feel threatened.

It may be tempting to conclude that the very early use of “regenerative” for organic farming is a mere coincidence and that the recent reemergence of this term is unique. However, congress explicitly included the word “regenerative” along with “organic,” “alternative” and “innovative” in the proposed farming act of 1982 (HR 5618), and a supplemental bill — Senate S 2485, which was drafted but not submitted — would have substituted regenerative for organic.

Moreover, it is remarkable that these early events were largely coordinated by a family private enterprise — Rodale — which previously originated America’s first organic magazine and then in 1982 launched the New Farm magazine (subtitled “The Magazine of Regenerative Agriculture”). Had these congressional bills succeeded, things would be very different now, as organic would be regenerative. New programs trying to gain acceptance would have had to choose other names and new metaphors among many possible themes on the diverse trajectory to system health, as suggested by Dr. Janzen’s work (see Figure 4).

Clearly, the expression “regenerative” is being used too casually. This has several consequences. It obscures recognition of regenerative biology — an important discipline of science concerning nature’s unique abilities to heal and rebuild damaged tissues. Dr. Bruce Carlson’s work on regenerative biology will delight and surprise anyone who wants to dive into it — the point being that what regenerative means scientifically is not what regenerative farming is talking about. We’re not regenerating soil, or soil aggregates or soil carbon, by using cover crops or compost. We are restoring deficient components and sustaining natural reproduction and microbial biomass — all quite ordinary processes. Earthworms do regenerate their bodies when cut apart — such as by soil tillage. The science of restoration is in its infancy and needs to be further developed to improve our understanding of how to harness reconstructive and healing processes in nature.

Another consequence of casual use of regenerative is obvious: in its present form, it means whatever an individual chooses to interpret, making it easily manipulated. The fact that business and agrichemical sectors have launched their own regenerative forums is an example of this open license.

In this sense, making tillage the key culprit of non-regenerative farming is not the point and may obscure the more pressing issue of the inputs in conventional farming — such as fertilizers and pesticides — that are known to be damaging to soil flora and fauna, worker health and water quality. In the case of chemical nitrogen, this is becoming an increasing urgency since the entire Midwest and California, Pennsylvania and Maryland are experiencing a significant upward trend of nitrate-contaminated groundwater, affecting over 4,000 rural communities with reported adverse human health effects, documented by meetings in 2021 by the National Academy of Science and Engineering.

Fertilizer reductions may become mandatory (they are elsewhere in the world) but are likely to reduce high farm yields, which incidentally are the key discriminator against organic (and regenerative) farming. These high yields have been acquired at a significant cost to the environment and are externalized in conventional farming. An Illinois study established that organic farming significantly reduces nitrate in groundwater and early Swiss research by Dr. Hardy Vogtmann showed that organic methods significantly reduce excessive nitrate uptake in plant tissue, making them clearly healthier for consumption. Regenerative will have to do at least as well to be able to maintain its popular title.

It is concluded that the main contribution of the new label “regenerative” is to restart the discussion begun nearly a half-century ago by maverick organic and eco-farmers. It is serving to stimulate intense debate and scrutiny of conscience on a broad scale, and this may lead to progress. Without standardization, however, it is not likely to contribute something that is distinguishable from most practices, and this will harm market potential.

William Brinton is the founder of Woods End Laboratories. Learn more at woodsend.com.