If you (hopefully) read John Kempf’s article in this issue of Acres U.S.A., you’ll recall the story he told about a dairy farmer in Ohio who begrudgingly realized that his high-clay soils — no matter how high the organic matter — needed drain tile in order to move water out of his pastures at certain times of the year. Yields went up 40-50 percent. John’s punch line was that in order to take yields to an even higher level, the farmer would need to also add irrigation. Such is the environment we live in. We need to acknowledge the fact that at some point, every operation experiences excess water, and adding drain tile would improve things; simultaneously, every farm at some point experiences drought and could benefit from irrigation. Doing one, not to mention both, isn’t economically feasible on many operations. But as a simple proposition, yields and quality would improve if every farm always had access to both in order to maintain optimal levels of soil moisture.

Keeping It Green by Jim Gerrish is a very practical manual for managing livestock via rotational grazing on irrigated pastures. It’s published by Stockman Grass Farmer — a publication similar to this one, except that it focuses exclusively on livestock operations. Gerrish covers five categories of irrigation and discusses the pros and cons of each, particularly in relation to grazing livestock.

Flood irrigation, which relies on various dams and diversions to streams, is the simplest and least expensive irrigation system. It works best with land that has just 1-2 percent slope, although it can handle up to 8 percent.

Solid-set sprinklers, hand lines, and wheel lines are different types of sprinkler systems that are linear in nature; Gerrish acknowledges the limitations of these: that cattle are prone to rub against and destroy manmade objects in their pastures, and protecting them with electric fence presents the risk of shorting out the fence.

Line-pod systems, like the New Zealand-made K-Line, are sprinklers connected by HDPE pipe that the farmer drags in a line behind a vehicle. They can water 6- to 8-acre pastures, enabling rotational grazing on small- to mid-sized farms.

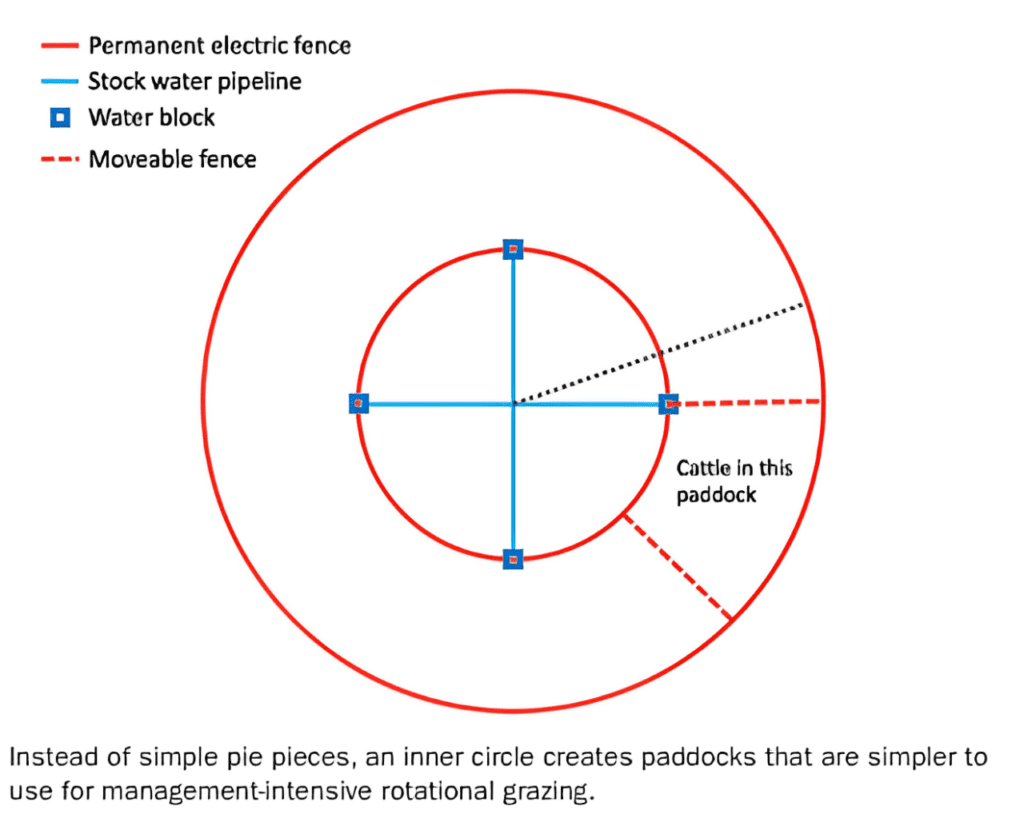

Center-pivot irrigation is of course ubiquitous in some parts of the country, although using such a system for grazing is not. Gerrish helpfully includes diagrams of how he breaks down grazing cells within these — instead of simple pie slices, he installs a fence halfway between the outer ring of the pivot and the center, and then puts in four water tanks spaced evenly around the inner circle.

Subsurface irrigation is seldom used for pastures due to cost, but Gerrish describes the conditions in which it may make sense and some basic principles for design. The book also contains a short discussion of water rights. It’s obviously not comprehensive, especially since this is such a complicated and controversial subject in the West. But it’s a helpful reminder to those of us east of the Mississippi that we should at least maintain a measure of gratitude that we don’t have to worry about such things!

Gerrish concludes the book with discussions of fertigation for pastures, getting the most out of an irrigation system, and the economics of each option. This is admittedly a niche topic — not every livestock operation has irrigation, although this book could certainly help persuade some who are on the fence to get it. And Gerrish doesn’t really deal with the environmental/ecological issues associated with pumping from (and helping to deplete) ancient water reservoirs — although he does encourage the use of “active” water from reservoirs that are being restocked, as opposed to “passive” ones that are not being significantly recharged. The challenges and ethics of the use of passive sources is covered in plenty of other resources; Gerrish assumes their use.

I’ll end with an anecdote from my cattle days. The farm I worked on was trying —financially unsuccessfully — to grass-finish cattle on heavy clay soil in Alabama. There’s a separate conversation to be had about what “grass-finished” really means — legally, albeit perhaps not ethically, it means that it’s OK to feed non-corn, non-soy feedstocks such as peanut meal and cottonseed. Even with purchased feed, though, it was only really possible to finish cattle there a few months of the year.

There was a farm in our network, though, that was able to produce excellent “grass-finished” cattle most of the year. They had sandy soils, but they were able to meet their targets because they had irrigation. They would feed the cattle and rotate them through the pastures, and they would seed and irrigate behind the cattle so they always had a good supply of grass.

As in this example — a location with 45+ inches of annual precipitation — irrigation has the potential to make a farming operation quite a bit more profitable. This book does an excellent job of explaining how.