Utilizing a simple process of observing, orienting, deciding and acting can help farmers make better decisions every day

Decisions. Each of us makes hundreds of them every day. Simple things like what clothes to wear, what to eat or drink, what to say to our friends and family. We also make very consequential choices, like if/who to marry, what career to undertake and how to arrange our life priorities. Various sources estimate the average adult makes upwards of 35,000 conscious decisions every day! Decisions literally are the stuff of life.

We all know people who make decisions based on emotions, others who make it from a carefully thought-out process, and yet others who are paralyzed to make a call when the moment arrives.

I think most of us make decisions without a whole lot of thought about how we actually do so. At some point, though, we need to ask ourselves what methodology we’re using, and why. A combination of influence and instinct is most likely what we subconsciously employ for every decision, from the mundane to the impactful. Sometimes it works out; other times not so much.

If we regard our brain as a toolbox, what tools can we put in it to aid in the process of making better decisions? In order to move soundly through a process of action, we need both a big-picture way of processing information and a small-picture, easy-to-cycle method. SWOT analysis — strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats — is a good framework for what I call “strategic thinking” — the broad-strokes, big-picture methodology for assessing decisions and arriving at one appropriate for your context and goals. It’s a great analytical tool, but it’s not the most expedient process when attempting to get a herd of animals to do something or when reckoning with a widow maker tree hung up over the fence. What’s also needed is a complementary methodology of “tactical thinking” — a specific action intended for a specific result, for an in-the-moment application.

Enter the OODA loop: observe, orient, decide and act. The “loop” references a continual cycling through these points as a situation develops. It’s meant to be a fluid process for dynamic situations.

The OODA loop was developed by an Air Force colonel named John Boyd as a way to describe the methodology used by his Air Force pilots in the Korean War to defeat Soviet aircraft and pilots with what was, at the time, an inferior U.S. Air Force fighter jet.

What Boyd found was that by cycling through this decision-making process, American pilots could arrive at a superior position in air-to-air combat in spite of the mechanical limitations of their fighter jets and could defeat the better-made and faster Soviet aircraft in up-close dogfights.

The American pilots would observe the enemy position, orient themselves in relation to the enemy aircraft and things like terrain features of the ground, decide on the appropriate tactic, and, most importantly, act. This cycle was repeated almost continuously as new data became available to the pilot, both from his eyes and via the guidance systems of his aircraft displays. This methodology led to a vast improvement in the success of American pilots in combat, and after the war Colonel Boyd found a much wider application of the OODA loop method in business, technology and strategic planning.

I have found that using the OODA LOOP in a wide variety of scenarios on the farm can give clarity of direction and a faster ability to make sound decisions in the moment. I like using an analogy of working animals in a corral, as it may be the closest a farmer gets to what Colonel Boyd describes in his writing about the OODA loop: a fast-paced environment with potentially dire consequences, where one must continually cycle through a rapid decision-making process in order to achieve a successful result.

While working animals in a corral, I need a continual looping effect of observing the animal, orienting myself properly in relation to the animal and where I want it to go, deciding what the next appropriate move is, acting on that, and then immediately restarting the process. Sometimes all of that happens in just a second or two. Another application would be the proper and efficient use of equipment — although hopefully at a more careful pace!

Observe

The first step in the loop asks us to do something that might be difficult: to pause and observe the object that we intend to manipulate or move. Observation first means that we recognize there is an object in our view, be it a non-physical problem or a very physical bull in the corral. It is a conscious registration that there is a situation at hand and that sometimes that is the biggest obstacle in our head. We don’t register that there is a developing situation that needs attention because we are distracted, absent minded or just don’t care enough to look around.

Observation is also about gathering information and accessing the potential action the object may take. How many different data points can be gathered before moving onto the next step? Some situations grant time for a detailed look; others, such as the corral scenario, give just a few seconds. The bull in the corral can take several actions very quickly if he wants too. Observation is a continual feedback loop inside the greater OODA loop.

Orient

Orientation is the critical step of taking the information gathered by observation through a triangulation process. What does the situation present itself as, what are the various potential outcomes based on its position, and, most importantly, what is my orientation to both the situation and the various outcomes? Going back to the bull in the corral analogy, he may be equally close to the trailer and to the gate out to pasture, but where is my position in relation to the trailer and the gate? Depending on my orientation, he may be successfully on the trailer in a few seconds or he may be kicking up his heels on the way to the back forty.

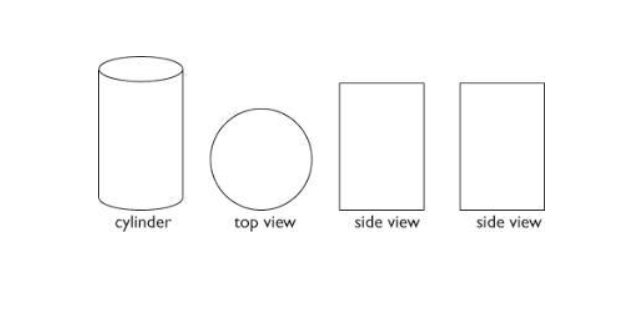

It cannot be understated that understanding that orientation is going to be different every time and for every person. As the graphic shows, you may see a rectangle, but someone else will see a circle, and yet others a cylinder. Same object, different orientation.

I may think a situation in the corral is well in hand because my orientation doesn’t allow me to see the unlatched gate in the corner, but my buddy helping me out is standing at a different angle and can observe the potential for something bad to happen. Hopefully I’ve done my job in teaching him this process so he can immediately work the OODA loop and maneuver around to shut the gate.

Decide

Any decision is a judgment call — the more observations one can make, contexting that with orientation to the situation, hopefully renders a better judgment. I may not have all the pieces I would like, but in some scenarios a decision must be made immediately. Perhaps that is the first decision to make: is this a fast scenario or one I can take some time with?

I like a thing called the iterative process, where decision making is reduced down to the smallest step possible. Instead of making a grand decision, what is the first small decision I could do without over committing to an action, with potentially bad consequences further down the process I can’t observe at this time? Maybe the first decision I make in the corral is to calmly move over to the fence the gate is on, observe the bull, and re-orient. All my options are still open.

It can be easy to slide into a thing called “paralysis by analysis” here, where mentally getting bogged down in the assessment of everything paralyzes one’s ability to make a decision. This is extremely common in high-stress scenarios the military operates in, and the remedy is to mentally detach from the situation, stand back and run the OODA loop while simultaneously inoculating yourself to the stress through practice, repetition and experience. Farming can have its share of high-stress situations too, as in our bull-in-the-corral analogy; if he’s moving, I can’t stand there and think about it for five minutes — I have to make a decision right now.

Act

A man I have much respect for is retired U.S. Marine Colonel David Berke. His career in military aviation is remarkable, and he is the one who introduced me to the concept of the OODA loop. In his opinion, “act” is the most important element of the loop. All the observation in the world can happen, the orientation can be this way and that, and decisions of courses of action can be arrived at — but without action, all of that is moot. Action is what puts everything in motion. The observe, orient and decide steps are all about bringing us to a correct action to achieve the desired result.

Back to the bull:

I observe the corral and the bull in it. I see the gate that mysteriously popped open. I also see that the bull sees it too.

I orient myself to the situation. I am in the corral, the bull is in the corral, and the gate and the trailer are about equal distances away. There are a few potential actions that could be taken.

I decide based on experience that the open gate presents the bull a more tempting action than loading himself onto the trailer, so I know that has to be my immediate area of focus. The trailer doesn’t matter at this point; removing the opportunity to bolt out the gate is paramount. It’s fine if he circles back in the corral; we can try the trailer again later.

I act by hopping over the side of the corral, maneuvering myself to both psychologically deter the bull from moving to the gate while also closing the distance to the gate myself. I grab the gate and calmly close it, setting the latch properly this time, and the situation is contained.

What do I do now? Right — the OODA loop again — but this time it’s a different scenario. The bull is safely contained in the corral and now we can focus on getting into the trailer.

Experience

I think a closing word about experience rounds out the OODA loop methodology. If you put an inexperienced person in that corral with the bull, that person’s ability to correctly utilize the mental tool of the loop is going to be fairly limited. You cannot replicate or replace a quality level of experience in any situation.

Just as Colonel Boyd’s pilots did better in combat over time by using the OODA loop, it was their experience that sharpened their ability to assess each point and cycle the loop faster and faster. The same thing applies to any scenario in life. Mark Twain once said, “A man who carries a cat by the tail learns something he can learn in no other way.”

You can always tell who’s the experienced cattleman from the big talker by putting them both in the corral with the bull. The man with the experience will be apparent quickly. You can tell who the experienced salesperson is by the way they observe the customer, orient their pitch to that particular person, decide on a route of conversation and act to close a sale.

Mental tools like the OODA loop are only as good as the operator of these tools. Proficiency in anything takes repetition, thought and experimentation. The more you can use these and other tools, the more instinctual they become until there are no stops and steps — there’s just a consistent flow of proper actions.

Jordan Green is a full-time regenerative farmer and a Marine Corps veteran. He and his wife, Laura, founded J&L Green Farm in 2009 in Virginia and directly retail pasture-raised meats. You can find him on most platforms by searching “farmbuilder”.