Changing the way we think in order to advance agriculture

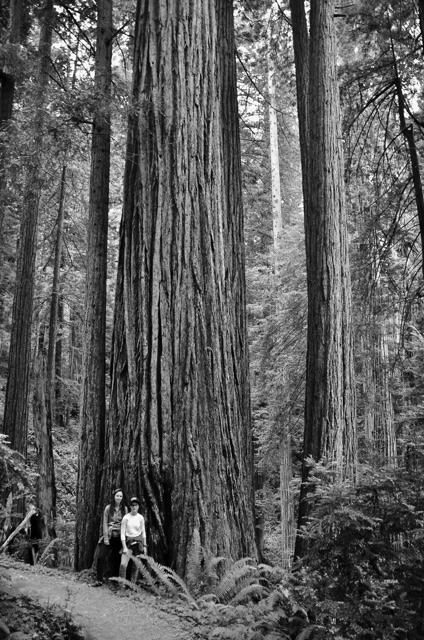

Fifty years ago, Wendell Berry wrote the poem Manifesto: The Mad Farmer Liberation Front not as a call to arms, but a call to a certain kind of madness. The speaker contrasts the sanity of modern economics with the madness of agrarian economics. Some of my favorite lines in poetry are embedded in these stanzas, including this one: “Plant sequoias. Say that your main crop is the forest that you did not plant, that you will not live to harvest.”

This is true madness. Think of the labor and the capital required for such a decision. There is no return here. There is only madness in planting sequoias; a return on investment stretches into centuries that will never come back to even the farmer’s children. From the savvy, business sense of the modern world, it smacks of idealism and even ignorance.

On the other hand, I believe we need more of this kind of madness in modern agriculture.

I am deeply committed to perennial agriculture, and my task in this article is to write about how perennial crops can potentially help growers transition to regenerative practices more quickly than annual row-crop systems. However, I’m concerned that this can be a false premise if we don’t truly change our agricultural mindset. Unless we perennialize our thinking, we run the risk of setting up new mechanistic, extraction-based models that will fail to be regenerative.

And as a corollary, the regenerative agriculture movement is in danger of replacing one mechanistic model for another unless we listen to indigenous perennial thinking, which has been regenerative for thousands of years. In other words, as we champion perennial crops, we must re-develop ecological-thinking — a cultural mindset of emerging perennial agriculture.

There have been rigorous debates between annual-crop proponents and perennial-crop advocates. Chris Smaje provides a nuanced view of the issue, suggesting that demonizing annuals misses the point: “If our goal is to match current yields of export-oriented, environmentally unsustainable annual cereals with sustainable perennial analogues there’s a danger of creating a permanent arable corner that makes the entrenchment of global poverty almost eternal” (Small Farm Future, 113).

I would add that perennial analogues of current simple annual systems won’t be sustainable, nor regenerative, but represent an entrenchment of mechanistic agriculture that constantly disrupts ecological processes. As we explore new (or very old) ways of growing perennial crops, we must continually remind ourselves that what we need isn’t simply a new technique, but a cultural revolution on how we view our relationship with the land, who has access to it, and our long-term net effect on ecosystem health.

Why Perennial Systems Aren’t Regenerative

There are two aspects of extractionist agriculture that can keep perennial systems from becoming regenerative. Both are based on mechanistic thinking that deconstructs natural ecologies.

First, we have to understand the processes that keep our farms input dependent. As a consultant and orchard manager, I’ve seen the economic effects on this dependence. Although these processes range from soil management to toxic-based pest and disease management, I want to highlight breeding and rootstock culture.

Based on what I’ve seen through observation, and poignantly through sap analysis, it can be quite common to see great variation in nutrient levels between crop varieties even when they are on the same soils and the same fertility program. Further, depending on nursery stock quality and propagation practices, mortality rates can range from 5 to 40 percent. A major problem in annual crops, breeding practices and seedling development in perennial crops can create agricultural systems that require heavy inputs or present fragility in the face of biotic and abiotic stresses.

And what about “regenerative fertility” programs? Modern varieties of both annual and perennial crops often require heavy external inputs due to bred deficiencies. Even if we succeed in reducing fungicide and pesticide inputs with regenerative management and well-articulated plant nutrition, the cost for regenerative products can be significantly higher. I’ve seen simple regenerative fertility costs for corn and soy range from $75 to $200/acre while perennial fruit crop fertility costs range from $600 to $1800/acre. Certain economic installation costs should be expected, but I believe we must honestly face the perfect-storm created around breeding and nursery practices that permanently install dependency on agribusiness.

In the past hundred years, conventional agronomic practices have bred annual plants that do not know how to take care of themselves. In parallel, we have also done the same to some perennial crops like peaches and apples. Not only has the culture behind these 100 years of agronomic practices created simplified, vulnerable systems that destroy topsoil and deplete biodiversity and nutritious food, but it has bred annual and perennial plants that are fragile and dependent on the broad array of products offered by agribusiness.

The second aspect of extractionist agriculture that can degenerate perennial agriculture is more deeply entrenched in the culture of our agriculture. Like many marketing narratives, regenerative agriculture is slowly morphing into an amoeba-like definition that engulfs the market on all sides. Everybody is in. If you ain’t “regen,” you’re behind the times. In a highly marketed industry, it can be easy to water down a revolution into a brand. It would seem the market forces around “regen” agriculture threaten to dilute the messaging into gobbledygook.

So, here is my baseline understanding of regenerative agriculture: Regenerative agricultural practices are implemented toward the goal of cultivating healthy plants, healthy soils, healthy food and healthy relationships. Broadly understood, health defines a kind of resilience against death and disease. And health is nested in every one of these levels, determining the health at other levels. Regenerative practices build and cycle carbon through proper soil care — they don’t burn it off the landscape. Regenerative practices cultivate diversity — they don’t kill everything except the human-defined “crop.” Regenerative practices cultivate living roots and livestock into seasonal cycles of energy; they are not simplified, bare soil systems. Regenerative practices maintain ecological relationships; they don’t dismantle them.

It’s this last aspect that I would like to highlight. Shifts towards perennial systems in regenerative agriculture hold promise not simply for a new suite of techniques, but for a cultural revolution on how we understand our relationship with the land and our neighbors. Thanks to the work of groups like the Savanna Institute, perennial-based agriculture and agroforestry models are gaining early adoption and are attracting necessary funding opportunities for installation costs and downstream infrastructure needs.

Adopting Agro-ecologies

All of this is important. Nevertheless, I would argue that a perennial turn in modern agriculture requires more than a new assortment of plants and market channels. It requires a certain kind of madness. To describe this counter-cultural madness, I would suggest we perennialize our thinking by learning from indigenous agro-ecologies.

The practices around “conventional” modern agriculture have decimated human communities and landscapes. Within 300 years in North America, perennial, regenerative systems that had co-evolved with human society for millennia were dismantled. These systems were built off thousand-year breeding projects for crops such as maize and housed a massive diversity of food crops, along with diverse meat sources. Beyond this, these indigenous food ways were open to new plants. Within a little over a hundred years from introduction, indigenous peoples had taken the peach of Europe, brought by the Spaniards, and cultivated perennial agroforestry peach systems without grafts and the whole array of fungicides and pesticides of today. In a common theme, early mixed peach orchards in the northeast and peach orchards of the southwest among the Diné were of such significance to food production that they were burned and razed to the ground by Europeans as strategies to permanently control local populations.

As another example, Mayan milpa systems are merely a small chapter in the numerous long-term breeding practices around annual crops in the central and southern Americas. Crops such as maize, squash and beans were part of perennial systems. Whether those fields followed riparian corridors or slash-and-burn forest systems, these annual crops were not only nested with perennial crops, but they were treated as perennial crops. Yearly breeding cycles created new expressions of plant-life, evolving both people and plant. In this way, people and corn found fitness in the landscape. Landrace seeds are simply perennial expressions of annual crops. You can’t have maize resistant to rust without perennial thinking and decision-making.

We divide annual plants from perennial plants due to different adaptations to reproductive and growth strategies. However, this division breaks down if you begin to consider that our management and selection choices are always interplaying with dormancy cycles. Rings on trees can show yearly cycles of precipitation and even management. On the flip side, our selection of annual seeds can illustrate the short-term or long-term focus of our agricultural systems. Consider the decade-long strategies of seed selection, separation and re-integration of traditional maize practices that maintain genetic diversity and perennial seed biomes in some indigenous systems. I think it can be argued that the genetics and seed microbiome of these seeds represent the accumulation of analogous tree rings in perennial crops.

From this perspective, the industry in perennial crop nursery development is more annual than perennial. Whether it be continued grafting technologies or sterilant applications in the rootzone, we aren’t thinking perennially. In the starkest of terms, perennial thinking simply works to save energy for the long-term viability of life in a local environment. We need more nurseries developing own-root tree crops, propagation of varietal-based micro-biomes in the root zones, and varietal selection based on reduced-input management. As it stands now, we select and market varieties that require inordinate amounts of external inputs, such as calcium, just to avoid massive crop loss from disease. We also need to listen to the rich, cultural, and agricultural traditions around saving seed — perennial practices that fit plants with people and land.

From emerging networks working for landrace seed development like Going to Seed to small nursery systems like Silver Run Forest Farm to largescale hybrid swarm research and tree propagation as at Badgersett and perennial tree and animal integration into cooperative models, like the work done by Tree Range, there are people and institutions pointing the way toward a perennial return to indigenous, regenerative agriculture.

These groups all express a kind of madness — at least from the perspective of modern agriculture. A refusal to control genetic diversity. Experiments in gift economies that keep agrarian economies regenerative. And immersion into ancient, perennial food ways that resonate deeply with local lands. It is a madness that puts value in perennial thinking, even if that means cultivating ecologies that stretch into the timescale of sequoias.

For ten years, I lived with a subsistence, agrarian people called the Yao in northern Mozambique. During that time, I learned more than any college class had ever offered. Amid any village problem or challenge, the representative community would gather. Children, newly married couples, fathers, mothers, and elders … all participated in the problem solving and discussion. But when wisdom was sought, the community stopped to listen to their elders.

As a consultant, this isn’t the conversation to be had in a one-hour interview with a grower who exists on the brink of economic collapse. However, all of us need the time and creative energy to network with old agrarian systems. So much of our current agronomic practices are cultivated by larger economic and agronomic assumptions. Those assumptions are the driving engine of topsoil loss and nutrient-deficient food. To give lifeblood into a perennial turn, we must make sure our assumptions and agri-culture are also turning.

Kyle Holton is a consultant with Advancing Eco Agriculture.