As ecological farmers, we can nurture the process of forming rich soil and healthy crops

How is it that this planet is covered in a mantle of green? How is it that since the dawn of human memory, plants have grown and flourished, creating tropical paradise or forests and meadows so lush and fair that poets and bards have sung of their beauty for millennia?

Even in the coldest polar regions, wherever a bare patch of the planet is exposed, plant life finds a toehold and survives as algae and mosses begin the slow process of colonizing the surface. Not even the blazing heat or extreme aridity of equatorial deserts can stop plants from growing. Not even volcanic eruptions nor radioactive meltdowns have been able to prevent plant life from taking over any available surface of the earth in its own due time.

The first astronauts that landed on the moon with their bulky pressurized space suits took samples from the lunar surface and brought them home to Earth for analysis. Since then, humans have sent probes to Mars and several asteroids to gather samples of material. In all cases, it has been discovered that Moon rocks, Mars rocks and the like are similar in composition to Earth rocks. So far, in our discovery of the solar system, rocks are rocks.

Whether on Earth or extraplanetary bodies, “rocks” break apart into smaller and smaller pieces of themselves. Silica-based rocks break apart into smaller silica rocks. Aluminum to aluminum, iron to iron, and so on. This process is called “weathering.” The expansion and contraction of matter due to heating and cooling caused by solar radiation breaks rocks into smaller and smaller pieces, as does impact from meteors and mechanical abrasion from debris flows. Winds caused by heating and cooling of the surface pick up the finer mineral particles and sandblast one another. Liquids (water on Earth, carbon dioxide elsewhere) transport mineral particles that erode larger particles; more significantly, liquids chemically react with the minerals to dissolve them further and to transform them into new compounds.

The Moon, Mars and asteroids are comprised primarily of minerals: bedrock, broken rock, and smaller and smaller particles of those minerals, forming rocks, gravel and dust. The Earth, however, is different.

The Input Trap

When the first European settlers arrived in North America and wrote about what they discovered, the common thread through most of their words was their astonishment at how lush and luxurious the plant life was. These plants, of course, nourished all of the other life forms that inhabited the continents of this hemisphere. Paleobiologists (those who study preserved and fossilized remains of ancient living organisms) have unearthed treasure troves of plant and animal species that boggle the mind in sheer numbers and diversity. Something radically different is happening here on planet Earth that we are not aware of anywhere else. In the presence of water and life, the mineral “bones” of this planet have been transformed through time and have become cloaked in a thin layer of what we call soil.

Those of us who are farmers or ranchers know all too well the importance of rich, fertile soil. We depend on it for our livelihoods. We employ a host of techniques and use an almost encyclopedic suite of amendments in order for it to produce economic quantities of whatever it is that we grow. Increasingly, farmers and ranchers are aware of the fact that by interacting with their soil in certain ways, they can increase the quality of the crops they grow in order to extend the shelf-life of produce, increase the pest and disease resistance of their crops, as well as optimize food’s nutritional content. Ten-acre homesteaders and front-yard gardeners use a different suite of techniques than row croppers or ranchers, but the goals are the same: to increase the overall health and fertility of our soil so as to experience vigorously growing, abundantly yielding, pest- and disease-resistant, highly nutritious crops, whether for animal feed or for human consumption.

The options for us today are as great as they have ever been. We can buy almost any custom-designed chemical powder, granule or spray to do almost anything we want. We can buy bulk biological products from compost and earthworm castings to microorganisms and inoculants. We can apply these products using satellite-guided robots if we want to. We can use a custom-designed suite of cover crops to increase soil organic matter and accumulate specific soil minerals. We can change tillage methods or stop tilling altogether. We can spray or not spray — organic, biological or conventional/chemical.

These are all options. All of them will cost money, of course, as does the equipment necessary in order to use them; therefore it is in our best interest to have an understanding of how soil is created and how soil health is maintained and improved.

Remember: the abundance that our ancestors knew — deep, fertile topsoil, prairies with grasses taller than a horse’s head, flocks of birds that could blot out the sun for days — was all created at zero-dollar cost and required no expensive equipment. People on all continents were a part of these systems since the dawn of human history. In many cases, early humans were part of the reason such abundance existed.

How Rich Topsoil Is Created

When we understand how rich topsoil is created, we can imitate those processes on our own operations so as to increase the health and fertility of our soils while minimizing costs.

In the April issue of this magazine I discussed an ecological understanding of disturbance, succession and regeneration. It is through these processes that soil is created.

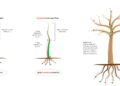

Let’s start with a simplified example. Imagine almost any bare piece of exposed bedrock. Sooner (in humid regions) or later (in dry areas) that exposed bedrock gets colonized by lichens. Lichens are a fascinating organism that have been understood to be a symbiotic association of cyanobacteria and fungus (modern science is now theorizing that there might be even more going on than just two symbiotic organisms). The cyanobacteria (algae) photosynthesize in the presence of sunlight and create simple sugars. The fungus absorbs some of these sugars and secretes acids that dissolve the rock beneath it and forms chelates, a combination of mineral and organic molecules. These chelated minerals are the fundamental building blocks of agricultural fertility. They are biologically available mineral nutrients with a wee bit of energy attached to it.

The lichen carries out the business of daily living, expands itself, divides into multiple copies of itself, grows larger and eventually dies. The skeleton of the now-deceased lichen (complex carbon/mineral compounds of numerous kinds and properties) is decomposed by a wide range of simple organisms and creates a basic humus. Decomposed lichen bodies are some of the most primitive of “soils” as we know them.

As the lichens continue to persist through time, this proto-soil continues to accumulate and to provide a home to more complex organisms. Some of the early ones might be mosses. As the mosses live and die, their bodies decay and add their nutrients to the accumulating soil.

Eventually, enough soil is created to support ferns and grasses. In the process of living, growing, reseeding and dying, the more complex plants add their bodies to the mix and the soil is deepened and becomes more fertile and more complex. In time, woody species, beginning with sun-loving shrubs and trees, transitioning to those that are shade tolerant, are able to colonize the site and add the products of their life and death to the accumulating soil.

The process of soil initiation is called “pedogenesis,” and the phase of increasing soil depth and fertility is called “aggradation.” While the process varies by location, this is where your soil came from!

Nurturing Succession

At any point in time, this developing system might get ecologically disturbed. Perhaps a fire races through, burning off the surface vegetation or even burning the accumulated organic soil (in cooler or wetter climates, organic soil can accumulate as “peat,” which is quite flammable). Perhaps a large herd of herbivores tramples overhead and grazes the vegetation, and possibly rips the sod exposing the subsoil or bedrock. Maybe a windstorm comes along and knocks down trees, tearing roots from the ground. Perhaps a novel disease comes along and wipes out a large number of individuals, or perhaps causes a population to become totally extinct. These disturbances set back successional development in chronological time.

What do these disturbances look like in modern agriculture? As an example, late last summer, a cover crop was planted into a ripening corn crop, or a legume crop was drilled into a heavily grazed fall pasture. This spring, the new cover crop is terminated and incorporated into the soil to feed the next crop.

Modern rescue chemistry makes it entirely possible to grow corn after corn after corn for a number of years. The limits of how long this can continue is being discovered every day as our topsoil washes away, as yields and profits stagnate, and as our neighbors and family die from chemically induced cancers.

The ecological farmer understands how soil is created and how its health and soil fertility is increased and maintained according to “Nature OS.” Disturbance is followed by the regeneration of the system (weeds are nature’s way of continuing the process without your assistance). Cover crops and your next crop are your participation in the process of soil creation and development. The remains of this season’s crop, along with the wastes of a whole panoply of herbivores (insects, birds, amphibians, mammals, etc.) are the food for the next successional phase. Our job is to understand these cycles and interact with them in order to husband our soil along the aggradation (instead of degradation) pathway.

Should the doomsday prophets prove to be right, and our farmlands turn into barren wastes and industrial humans become extinct, the processes of pedogenesis, succession and aggradation will continue without us. Why wait for that to happen? Let’s continue on the path of ecological farming and help to create the next successional phase of human development by naturally increasing the depth and fertility of our topsoil and by producing the most nutritious and delicious food possible, so that the good that we do can spread far and wide.

Mark Shepard is a land designer and consultant and is the author of Restoration Agriculture, Water for Any Farm and the Water for Any Farm Technical Manual.