Farming to optimize plant-microbe interaction is the best way to ensure the food we eat contains the phytochemicals that will make us healthy

It is just common sense that to be healthy you must consume healthy food.

Healthy food is defined by its ability to nourish the body with essential nutrients while minimizing harmful substances. It plays a vital role in maintaining physical, mental and metabolic health, supporting the prevention and management of chronic diseases, and promoting long-term well-being. A balanced diet incorporating a variety of healthy foods is key to achieving optimal health.

The Importance of Phytochemicals

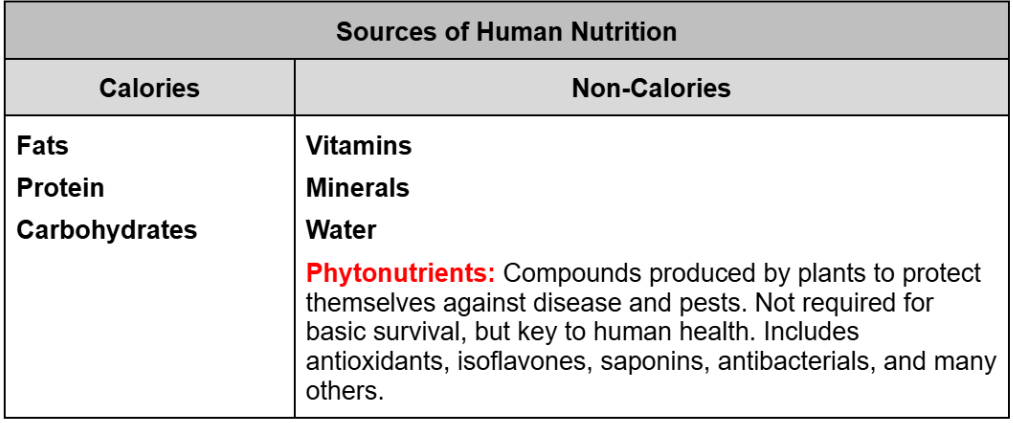

How can this be quantified — i.e., what are the important substances that make up nutritious food?

- Healthy food is typically nutrient-dense rather than calorie-dense, meaning it provides a high concentration of vitamins, minerals, fiber and other beneficial compounds relative to its caloric content. These beneficial compounds are mostly phytochemicals — compounds produced by plants to protect themselves against disease and pests. Unlike essential nutrients, phytochemicals are not required by humans for basic survival but offer significant health benefits.

- Many phytochemicals have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer and other health maintenance effects in humans. Although not essential (like vitamins or minerals) phytochemicals contribute significantly to disease prevention and overall well-being and are probably the most underrated component of healthy food.

There can be no argument against the fact that our food’s nutritional value has declined dramatically over the last number of years as measured by the nutrient mineral and vitamin values. We don’t have much information on the phytochemical decline, but it would be very surprising if it did not follow the same trend.

The Decline: Breeding for Abiotic Nutrition

What are the main issues responsible for this dramatic decline in the nutritional status of food?

The desire for higher and higher crop yields has focused plant breeders on developing new cultivars that achieve this at the expense of nutritional value. These selections are usually made inside systems that use large amounts of external fertilizer inputs, which naturally shut off the ability for the plant to interact with microbes — and this interaction is what drives the plant’s biotic nutrient absorption process.

We can divide a plant’s mineral nutrient absorption mechanisms into two broad categories: biotic and abiotic.

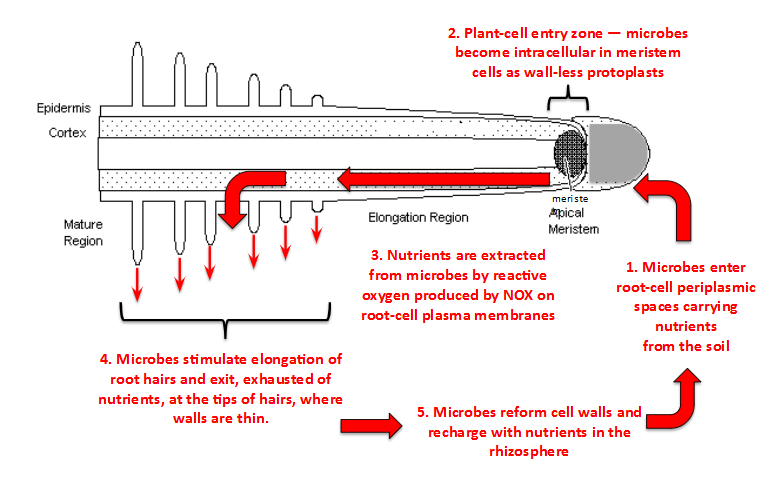

The biotic mechanism relies on wide and diverse soil microbial communities that locate, solubilize and transport the mineral nutrients to the root prior to the absorption process. These microbes are compensated for their service with root exudates, which contain sugars and other substances that feed them.

The abiotic mechanism relies exclusively on physical and chemical processes and is dependent on nutrients being in a soluble form and coming into contact with the plant roots. This process is highly pH dependent.

With the advent of modern high-input agriculture and the use of fertilizers, the biotic mechanisms driven by mycorrhizae root colonization and the rhizophagy cycle have been largely ignored. The emphasis has shifted to the abiotic process, with the external application of mineral nutrients in a solubilizable form. In tandem with this, the breeding and selection of new row crop cultivars made significant advances with yield increases but were selected in systems with large amounts of external applied fertilizers with little or no consideration of biotic plant-mineral absorption processes. With these biotic mineral absorption processes being largely ignored, it appears as if the genetic trait associated with biotic processes are in decline in the gene pool of these high-yielding, high-input cultivars.

These selection processes for high-yielding cultivars also result in primary metabolism becoming completely dominant in these cultivars, with a concomitant decrease in the requirement for certain essential micronutrients such as cobalt, nickel and selenium, which are required for the secondary metabolism processes. The absence of secondary metabolism, which synthesizes the important phytochemical components as well as vitamins, is therefore depleted in these crops, as are the mineral nutrients required for secondary metabolism. Scientists now believe that as many as 60 mineral nutrients are required by plants.

It is not uncommon to see crops being grown hydroponically with only 13 nutrient elements being provided. This begs the question of whether there is any real nutrition present in these crops, as the secondary metabolism is null and void in such a growing system. This trend has implications for secondary metabolism, as several micronutrients are crucial cofactors or activators of enzymatic pathways involved in the synthesis of secondary metabolites.

Modern plant breeding and selection for higher yield, particularly in conventional high-input agricultural systems, has therefore inadvertently contributed to a reduction in the diversity of micronutrient content, reduced mineral nutrient density, reduced vitamin content and depleted phytochemical content in plants. This has led to a dilution effect: as plants are bred to produce more biomass or grain, the concentration of minerals (including micronutrients) in the harvested parts tends to decrease.

Wild relatives of crops, or older landraces, often contain higher levels of micronutrients and secondary metabolites and have high beneficial root associative characteristics. Secondary metabolites in root exudates shape soil microbial communities. Decreased production can weaken plant-microbe interactions and soil health. This is an extremely important issue, as a crop plant with weakened secondary metabolites may not have the correct signaling chemicals to attract mycorrhizae and other beneficial microbes.

The alarming consequence of this phenomenon in modern agriculture is that it appears that cultivars are adapting to the degraded soil conditions created by tilling, monocropping, fallow land and an overuse of fertilizers and chemicals, as these external inputs are regarded as substitutes for a diversity of soil life.

Mycorrhizae and Rhizophagy

What are we striving for in our food system? To produce crops with high nutritional values.

What are the basic requirements to achieve this? The first and most important component of such a system is choosing a cultivar that is adapted to a regenerative crop production system — a seed that has retained the ability to associate with the soil microbiology, thus providing all the necessary nutritional provision services. In this regard, mycorrhizae root colonization and the rhizophagy cycle are the two most well-known processes that breeders should select for.

We can confidently conclude that the present high-input agricultural cropping system is not designed to provide food with all the necessary nutritional components. Planting into — and breeding in — regeneratively prepared land that integrates cover crops and livestock is the only instrument for achieving this.

Willie Pretorius is a soil health consultant with degrees from the Universities of Pretoria and Stellenbosch. He would like to thank Dr. James White of Rutgers University for his valuable inputs for this article.