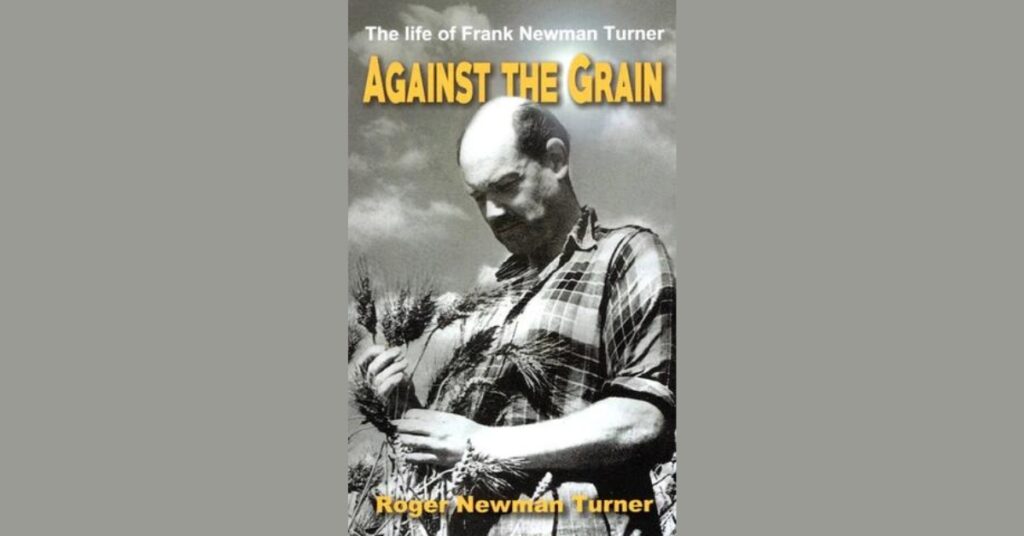

Against the Grain: The Life of Frank Newman Turner by Roger Newman Turner

“Frank Newman Turner, the son of Yorkshire tenant farmers, seldom ploughed a conventional furrow.”

So writes Turner’s son, Roger, in a new biography about the influential English farmer. Turner’s name will be familiar to many within the Acres U.S.A. community — he is the author (simply as Newman Turner) of four books written in the 1950s and republished by Acres U.S.A. in the 2000s: Fertility Farming, Fertility Pastures, Herdsmanship and Cure Your Own Cattle.

Turner was an independent thinker who became a pacifist in the 1930s and spent the war on a 200-acre Quaker farm in Somerset. There, inspired by his personal relationship with Sir Albert Howard, he began to experiment with organic methods of animal husbandry.

Turner believed that soil was best maintained without disturbance and soon eschewed the plow in favor of rotational grazing. The innovation he is perhaps best remembered for is the planting of “herbal leys”: pastures seeded with various combinations of herbs and grasses that offered free-choice nutritional options for livestock. He applied similar principles to human health as a medical herbalist and naturopath.

Turner had studied agriculture at university, but he also possessed a natural ability to write. In 1946 he began publishing The Farmer, an important, if small, periodical for those inclined to traditional yet innovative ways of agriculture. Faced with health struggles later in his short life — Turner died of heart disease at the age of 50 — he gave up farming but continued to write; The Farmer morphed into The Gardener, one of the first monthly publications devoted entirely to organic gardening.

A biography written by the subject’s son is bound to possess a certain amount of bias — possibly in either direction — and this one does err a bit on the side of hagiography. There are too many long quotations from letters, as well as details that would only be interesting to other family members.

But despite these quibbles, Against the Grain is a worthwhile read. It tells the story of an important figure in what would become regenerative agriculture, and it provides an example of the kind of innovative thinking — and boldness — needed to change the status quo. As Fred Walters writes in his 2008 intro to Fertility Farming, readers will “find lasting inspiration in Turner’s love of land and beast and his plucky attitude toward the conventional wisdom of his day.”

| From Frank Newman Turner’s Fertility Farming: When I came to Goosegreen Farm the first calf born was dead. Disease was already master of the farm. Was I to be man enough to face such a master and turn his efforts to my own advantage? I thought I was, but disease drained the resources of the farm for nearly five years, ruining nearly two herds of cattle in the process, before I reached a position of stability in the health and production of the farm…. When at the beginning of 1943 I had the opportunity to take the farm over on my own, I knew that half the cattle were barren and that I had a long history of disease to tackle. But I had faith in nature. The fact that not all the cattle had succumbed to contagious abortion and tuberculosis led me to believe that disease was not primarily caused by bacteria, but that it was the result of deficiency or excess of wrong feeding and wrong management, with bacteria only a secondary factor. Nature provides the means of combating all the disease that any living thing is likely to encounter, and I have discovered that bacteria are the main means of combating disease and not the cause of it as we had formerly believed. So I decided to get my farm and its livestock back to nature. I would manure the fields as nature intended; I would stop exhausting the fertility of my fields and give them the recuperative benefit of variety. My cows would no longer have to act as machines, with compound cakes going in at one end and milk and calves coming out at the other. I would return them as nearly as possible to their natural lives. The more natural parts of their diet—leys, green fodder, other bulky foods and herbs—would be assured and adequate quantities insisted upon before any concentrates were fed. All the food the cows and other livestock received would be home grown, on land filled with farmyard manure, compost and green crop manure. Artificial fertilizers, which had left my soil solid and impossible to live in, for almost any form of soil life, were dispensed with entirely. Not only because I was at last convinced of the disaster they had brought upon me, but because I could no longer afford to buy them. There was not enough ordinary muck to go round. But with the rapid ploughing up programme that the poor grass made necessary, and the consequent increase of arable acreage, straw was accumulating. Instead of tying up the cows in the winter they were given freedom and turned loose in yards, being milked in a milking parlour. Quickly the straw stacks diminished, not in smoke as so often happens on so-called progressive farms these days, but, by way of the cattle yards, they grew into tons and tons of compost which went to produce whole-wheat to grind into flour for bread, whole oats and beans to be ground for cattle food, and fresh greenstuff for all living things on the farm—soil, cattle and men. This kind of farming restored life to a dying farm. Everything on the farm, from the soil teeming with life and fertility, to the cows all pregnant or in full milk, and to the farmer and his family full of energy and good health, acclaim the rightness of this policy. My neighbours have, of course, questioned the financial wisdom of such a system of farming. They said that labour for composting would be higher than the cost of buying and spreading artificial fertilizers, and yields could not possibly compare. Costs certainly did appear to increase, for it seemed that we spent more time about the muck heap, and spreading the compost, than ever we did about handling artificial manures. But when it came to be worked out, the extra cost was nothing; for the men were engaged on the muck during wet weather, and at times when there was no other productive work for them to do. Previously we must have wasted a good deal of time on worthless jobs, when now all our spare time was building up fertility at no extra cost. I shall show in this book how it is possible for the average medium-sized farm to be self-supporting in fertility, and consequently free of disease, with less capital outlay, a reduction in labour costs, and an immense saving in the cost of manures and veterinary and medicine bills. But though there was a reduction in costs, there was a marked increase in yields. My threshing contractor tells me that my yields are not equalled in the district. Yet all my neighbours boast that they use all the artificial fertilizers they can lay hands on. But it is not in increased yields, or in costs, that I measure the success of this organic fertility farming, though these things are important in times of economic stress. It is the health of all living things on the farm that proclaims nature’s answer to our problems. From a herd riddled with abortion and tuberculosis, in which eight years ago few calves were born to full time, and those few that reached due date were dead, I can now walk around sheds full of healthy calves, and cows formerly sterile, now heavy in calf or in milk. I have advertised in the farming press for sterile cows and cows suffering from mastitis and have bought many pedigree animals, declared useless by vets, given them a naturally grown diet, and a period of fasting, herbal and dietary treatment which I have discovered to be effective in restoring natural functions, and they have subsequently borne calves and come to full and profitable production or had their udders restored to perfect health. Cows that have been sterile for two and three years have given birth to healthy calves. On the orthodox farm there is no hope for these cases, and the animals are slaughtered as ‘barreners.’ But nature intended the cow to continue breeding into old age, and if treated as nature intended there is every chance that her breeding capacity can be restored. I considered my pedigree Jersey cattle worth keeping and bringing back to production, and if I could buy similar animals with which others had failed, it was also doing good to myself as well as the condemned cows; and it has paid me both financially and in moral satisfaction. I have cows aged fourteen to twenty years which, after being sterile for years, have given birth to strong calves and milked well afterwards. In the process of all this work I have experimented with the use of herbs, in the treatment of animal disease, and discovered ways in which this science can be of use to the farmer in a fix with disease. I shall say something about such treatment in a part of this book, but I should stress at the outset that the main purpose of my book is to demonstrate the simplicity and effectiveness of farming by the laws of nature; and above all to show that it can be done on the poorest of farms, by the poorest of men. Such restoration of a dead farm is an achievement worth any man’s efforts, and success within the reach of any farmer who will turn back to fertility farming, and eschew the ‘get-rich-quick’ methods of commercialized science, which are in fact a snare. |