Dr. Laura Kavanaugh, chief science officer of Advancing Eco Agriculture, talks about third-generation DNA soil testing, which can provide greater understanding of how soil is functioning and greater applicability of that knowledge for farmers

Acres U.S.A. Can you discuss your background — your context and how you became the chief science officer at Advancing Eco Agriculture?

Kavanaugh. I have an unusual path. I actually started out as an engineer, and my first job out of college was at the Johnson Space Center, working on the space shuttle program. I did that for over 10 years. As that was winding down, I went back to school to get my Ph.D. at Duke — their program in genetics and genomics. I studied fungal genetics and how DNA jumps around between species.

After I graduated, I went to work for Syngenta for over 10 years, and that’s where I started the journey into GMO development. It was an awesome experience because I could connect with all kinds of crops and growers all over the world.

But in that process, I just came to decide that GMO approaches were not a long-term solution. We spent time calculating how long we thought GMOs would work until nature overcame them, and then tried to make increasingly more complicated systems so it would take nature longer. But in the end, nature is always going to win.

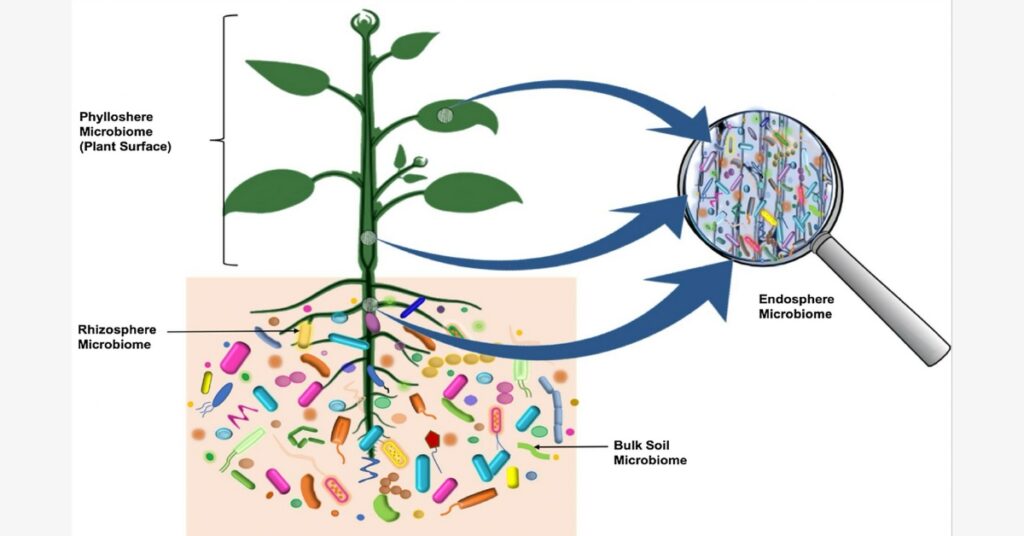

I decided, well, that’s not it. I started looking into soils and the interactions between plants and microbes. And not only does that help produce the healthiest plants, with the most nutrients and an immediate crop for the farmer, but there’s so many important long-term impacts. We don’t really talk about these much. I don’t quite understand why; maybe our thinking needs to be a little bit more long-term.

Soil microbes create water retention, so they’re hugely important in resistance to drought. They hold your soil, so you don’t have huge amounts of erosion. There’s a picture from the Smithsonian of a person standing on a road, and the farmland is about six feet below them because it’s eroded away. It’s so powerful because it’s hard to see erosion on a daily, human basis; but erosion is hugely impactful to farms. And there’s environmental pollution — all of our fertilizers are running into waterways, and we have these big red blooms.

Acres U.S.A. Can you explain a little bit more how you came to think that, long-term, this wasn’t going to work — that nature is going to win?

Kavanaugh. Sure. When you’re using glyphosate, for example, you quickly start to see these glyphosate-resistant weeds. You’re spraying millions of plants with this chemical that is designed to kill them, and it does kill almost all of them. But the ones that mutate and are able to survive — and the ones that just by random accidents survive the spraying — those are the ones that are going to propagate.

Nature is always experimenting. That was so interesting when I was studying genetics — DNA intentionally has mutations as it’s being copied. They’re very low level, because it can’t tolerate a lot, but they’re always being perpetuated in the natural system, and that gives the system the ability to adapt. Even though you might have a super successful system, nature is so dynamic that you always have to be experimenting so you could be ready for the next thing.

In the example of glyphosate and weeds, there’s going to be some mutation in some weed somewhere that, just by accident, is able to survive an application, and then that weed is going to perpetuate. It’s going to become the new progenitor, and that becomes a bunch of weeds. Over the course of time, when you spray billions of billions of plants, nature’s eventually going to overcome that. The companies try to stack traits, so there’s more than one thing to overcome; that might last longer, but they’re going to always be overcome by nature.

Acres U.S.A. Was any of your research into the difference in exudates from GMO plants versus non-modified plants?

Support authors and subscribe to content

This is premium stuff. Subscribe to read the entire article.