More should be considered when attempting to control plant pathogens

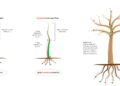

Elementary discussions of plant pathology almost always describe the disease triangle.

The foundational concept appears quite simple at first glance. For a “dis-ease” to express itself, a combination of three elements is required:

- A susceptible host

- A potentially pathogenic organism

- The proper environment

This seems like an obvious and simple explanation. We accept it without much question and move on to the next part of the discussion, which usually revolves around controlling “pathogens” when the combination of these three elements is met.

Rather than moving immediately to the control conversation — and assuming an infection has occurred that we have no influence over — we might dig a bit more deeply into each of the three elements. When we understand these three elements fully, they will give us all the information we need to prevent any “dis-ease” from expressing in the first place. Prevention is often easier and more effective than a cure.

When we consider the definition of a “susceptible host,” what are the parameters that define a susceptibility? What are the differences between susceptible and resistant cultivars? Does the organism require a certain amino acid and carbohydrate profile that some cultivars do not provide? What are the resistance mechanisms that are present in some cultivars, and in some growing conditions, but not in others?

What defines a “potential pathogen”? We know from the research being conducted on the microbiome — as well as the work described by James White and Don Huber, among others — that there is no correlation between the presence of a potentially infectious organism and an actual infection. Soil organisms that might become pathogenic (such as fusarium and verticillium) actually develop symbiotic relationships with plants when the plant has a healthy, disease-suppressive microbiome. For an organism to infect a plant and produce disease requires compromised soil biology and a compromised microbiome.

What defines a “proper environment”? Our first thoughts generally go to the external climate, humidity and temperature. What about the plant’s internal environment and the soil environment? From Olivier Husson’s breakthrough work on the biophysical environment required by different organisms, we know that each organism requires the plant and soil to be in a specific redox state. The plant pH and redox — and the soil pH, redox and paramagnetism — each need to be within a defined zone before an organism can infect a plant and produce disease.

The solution to effective disease prevention is actually very straightforward. We need to understand precisely what defines a susceptible host, a disease-conducive microbiome, and the internal plant “environment” for each pathogen. When we understand these elements, it becomes very easy to manage the crop in a way that prevents these organisms from producing disease — even when the organism is abundantly present and the climatic environment is considered ideal for disease expression.

John Kempf is the founder of Advancing Eco Agriculture and kindharvest.ag. He hosts the Regenerative Agriculture Podcast and is the author of Quality Agriculture.

Nutrient Management for Disease Control

We have known how to prevent and reverse plant diseases with nutrition management for a long time. The information is not new — it has just been ignored or forgotten.

Fertilizers and trace minerals can be used to increase disease severity, or to reduce or eliminate disease entirely. Many fertilization practices today are known to increase disease. This knowledge should be foundational for every farmer and agronomist, but it has largely been forgotten.

To illustrate how rich the literature is, here is an excerpt from the opening chapter of Soilborne Plant Pathogens: Management of Diseases with Macro- and Microelements by Arthur Englehard, published back in 1989:

A large volume of literature is available on disease control affects provided by macro- and microelement amendments. Huber and Watson in 1974 in “Nitrogen Form and Plant Disease” reviewed and discussed the effects of nitrogen and/or nitrogen form on seedling disease, root rots, cortical diseases, vascular wilts, foliar diseases and others. They summarized work from the 259 references in four tables in which they list crops, diseases and citations. McNew in the 1953 USDA Yearbook of Agriculture discussed effects of fertilizers on soilborne diseases and their control. He reviewed briefly specific diseases such as take-all of wheat, Texas root rot, Fusarium wilt of cotton, club root of crucifers and common scab of potato. Many other diseases were mentioned, as well as how macro- and microelements affect host physiology and disease. Huber and Arny in “Interactions of Potassium with Plant Disease” summarized in three tables the effect of K (positive, negative, neutral) on specific diseases. They listed 267 references in the bibliography ….

… [A] virtual flood of literature is available regarding the effects of macro – and micro element soil amendments on the level of soilborne disease in plants. What is lacking is the correlation of the positive factors into integrated production systems. The biggest problem now is how to organize and comprehend the mountain of available and often conflicting data. We have entered an era in which computer-aided analysis and other sophisticated tools are needed to integrate information and develop systems approaches to growing healthy, productive plants.

One of the most rewarding approaches for the successful reduction of soilborne diseases is the proper selection and utilization of macro- and microelements. Since virtually all commercially produced crops in the developed world are fertilized, it is extremely important to select macro- and microelements that decrease disease. This is an important and viable alternative or supplement to the use of pesticides which usually only give partial disease control.

For an up-to-date and more modern version of Englehard’s work, I highly recommend the book Mineral Nutrition and Plant Disease. This information has been available to agronomists and farmers for a long time. We just need to put it into practice.