Coppice Agroforestry: Tending Trees for Product, Profit, and Woodland Ecology by Mark Krawczyk

It’s easy to take for granted all the things trees provide us. Consider just a few from the list Mark Krawczyk compiles in his introduction to Coppice Agroforestry: building materials, shade, fuel, food, erosion control, climate stabilization, water cycling, wildlife habitat, medicine, air filtration. Not to mention beauty and inspiration.

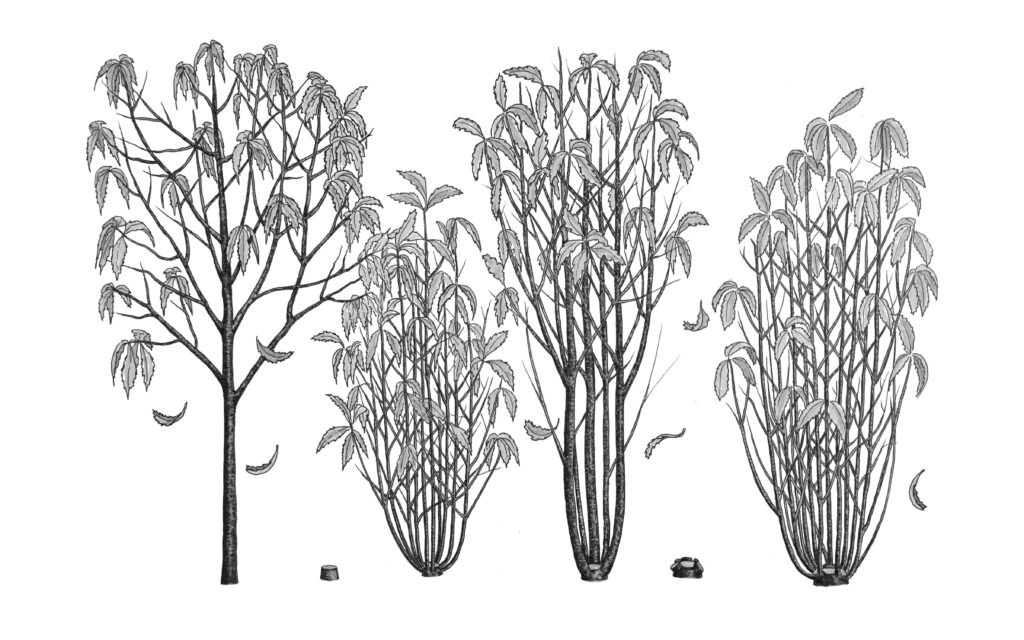

Coppicing is the practice of growing a tree — which begins life with a single trunk — and then, several years later, cutting it at its base while the tree is dormant and allowing it to sprout a number of new poles. Some years later these poles are harvested, again at the stump, during the winter, and the stump is allowed to again put out sprouts — the process continuing in a decades- or centuries-long cycle. Researchers have shown that coppicing can actually increase the lifespan of a tree by a factor of three or more.

The significance of coppicing is that it is basically a self-maintaining system — producing wood for many of the above-mentioned purposes over and over. The only human requirement, besides harvesting, is patience. And human interaction is beneficial for the tree as well.

Krawczyk goes into great detail on the science behind coppicing — how, after disturbance, trees are able to produce new sprouts from preventitious (dormant) buds that are embedded beneath their bark. The book also discusses the related phenomenon of suckering (the practice of trees like cherry and locust to produce new shoots from their roots) and the associated technique of pollarding (like coppicing, but the cuts are further up the trunk of the tree instead of near the ground, in order to keep the new sprouts out of reach of livestock).

Yet apart from its incidental practice when roadcrews try in vain to keep trees from invading the sides of highways, coppicing is rarely practiced in the U.S. today. In fact, it is a practice that European settlers never established here in the New World. In the Old World, where resources were much more scarce and costly, a practice like coppicing made sense. It required relatively little effort and was a local, renewable resource for building homes, constructing fences, providing heat, making tools and much more.

But here in America there were plenty of existing resources. Then, once coal and oil began to be used, the need for wood naturally declined.

Krawczyk makes the case for a renewal of coppicing, although he rightly recognizes that it’s not the right tool for all of our problems. There are healthy and productive forests that would be poor candidates for coppice conversion. Pine, which makes up much of our managed forests, generally does not coppice (although there are some forms of resprouting that could be used to manage coniferous plantations). And steel and plastic have of course become preferred materials for many modern buildings, vehicles and other products.

There surely is a place for coppicing, though. Rot-resistant locust and other species can be coppiced for the production of fence posts. Coppicing can be an important way to produce biomass for industrial use. It can be a used to grow material for furniture making and other crafts. And on the community/homestead scale, in otherwise unproductive or low-grade forests, it can be a very useful technique for wood production.

This book is a project that took author Mark Krawczyk over a decade of his life to write. It is thorough — encompassing nearly 550 pages — and while it may be a bit too much information (and too pricy) for the casual reader, for anyone interested in developing a sustainable community-level agroforestry system it will certainly be an invaluable resource.