Exploring the historical reasons why 40 percent of American corn becomes ethanol

“The earth has been tapped for petroleum fuel with a prodigality which cannot continue,” wrote a man named R. C. Farmer. “Already the demand is outstripping the supply, with consequent rise of price …. The desirability of drawing our supplies of motor fuel from recurrent vegetable sources instead of from the world’s fixed capital of mineral wealth is obvious.”

Farmer was an advocate for renewable energy, especially the use of plant-derived ethanol as a substitute for or additive to gasoline. His short book, Industrial and Power Alcohol, advocated the use of ethanol as “an alternative liquid fuel” for automobiles. Ethanol, he argued, could provide a renewable alternative to fossil fuels like crude oil and coal.

Oh, one other important fact about Farmer — he wrote this book in 1921. Farmer lived in England, which had just come through an oil crisis during World War I because it could not import enough oil to satisfy demand. While normal international trade channels reopened after the war, Farmer and others were still worried about the long-term sustainability of relying on a nonrenewable fuel for something as vital as transportation.

Worries about running out of petroleum were less common in the United States, but there were always a small minority of Americans who dreamed that someday the nation’s cars and tractors would be powered with homegrown, renewable biofuels.

Early Ethanol Debates

Until the 1940s, the United States produced most of the world’s oil. It is no coincidence that the ideas of individual automobile ownership for the masses and using tractors to replace horse-drawn farm implements both originated in this oil-rich nation. Importantly, although fermentation is an ancient art and distilled liquor played a notorious role in American frontier history, nobody seriously considered using alcohol for motive power before the 20th century.

It wasn’t until petroleum-powered engines came into widespread use that people began to consider using ethanol as an alternative fuel. In a 1907 bulletin titled The Use of Alcohol and Gasoline in Farm Engines, the USDA discussed the possible advantages of using ethanol to power stationary engines for pumping irrigation water, especially in remote regions where gasoline might be hard to obtain. But ethanol still cost twice as much as gasoline, making it economically unattractive as a fuel source.

Ethanol started to sound more attractive during the farm overproduction crisis of the 1930s. Some blamed the problem of crop surpluses on the accelerating transition from horses to tractors for farm motive power, which had opened up an estimated 35 million additional acres for row crops. The chemurgy movement suggested using surplus commodity crops as feedstocks for industrial processes, including ethanol production.

In a 1942 book titled Food for Thought, the Indiana Farm Bureau argued that using up to 35 million acres of American farmland to grow corn for ethanol would “go a long way toward solving the farm problem” and would be good for soil conservation because all the byproducts could be returned to the soil either directly or in animal manure.

These arguments seemed so persuasive that the oil industry grew alarmed at suggestions to incorporate up to 10 percent ethanol into the nation’s gasoline supply. Organizations like the American Petroleum Institute launched an anti-ethanol propaganda campaign, arguing in their 1940 pamphlet Power Alcohol: History and Analysis that ethanol was still much more expensive than gasoline and could not compete economically.

Playing into the environmental worries of the day, the American Petroleum Institute predicted that increasing corn production would lead to increased soil erosion, leaving the nation “with its most fertile soils depleted and large areas of croplands permanently exhausted.” Worst of all, forcing gasoline distributors to sell ethanol blends would mean that they would have to purchase new “storage and dispensing equipment,” an expenditure that would probably put a large percentage of the nation’s 700,000 independent service station owners out of business. Favoring farmers over these small business owners would “establish a dangerous precedent” and “lead only to confusion and injustice.”

In a 1936 article for Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, Gustav Egloff and J. C. Morrell from the Universal Oil Products Company predicted an even more dire future. They argued that it was easy to separate ethanol from gasoline by simply “shaking with water” and using activated carbon to remove “any gasoline taste and odor.” This reclaimed alcohol could be “readily flavored with prune juice, sherry wine, juniper, and other flavoring materials, to taste.”

“The death rate would probably go up from accidents caused by intoxicated drivers and a poisoned public, with the adoption of the gasoline tank and garage as a source of alcoholic beverages instead of the roadside tavern where the price would be much higher,” Egloff and Morrell warned. “If alcohol-gasoline become compulsory, organized crime might take over the business it established during prohibition and not only would the public suffer from racketeering but it would also be called upon to pay the bill for law enforcement.”

Whether or not propaganda like this had any effect on public opinion, interest in ethanol declined during the 1950s and 1960s. Oil prices were low and gasoline was far cheaper than anything even the most efficient ethanol plants could hope to produce. And the heady dream of unlimited atomic energy made worries about the ultimate depletion of oil deposits seem pointless; the future pointed to more energy, not less!

A Crisis in the Making

While some people in the oil industry tried to discredit ethanol, one petroleum geologist employed by the Shell Oil Company started to think about what would happen when petroleum supplies started to dwindle. As Mason Inman describes in his 2016 biography, The Oracle of Oil, Marion King Hubbert knew that oil production from nearly every known field followed a bell-shaped curve. First, production went up exponentially; then it leveled off; then it declined. Hubbert predicted in 1956 that oil production in the United States would peak also — sometime between 1965 and 1970.

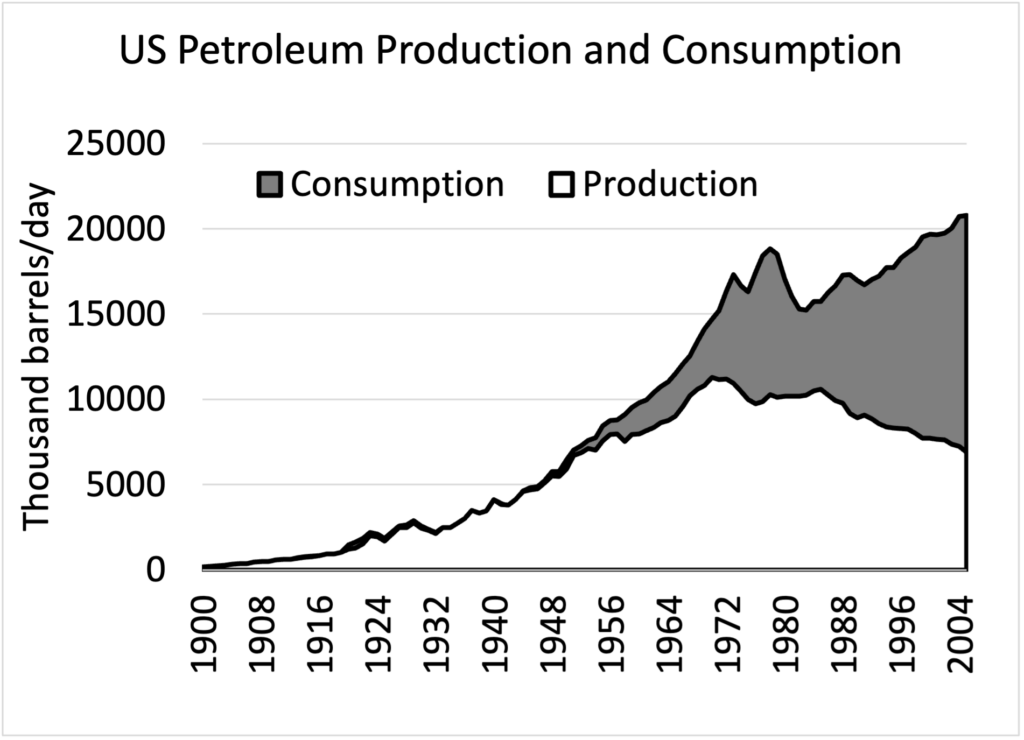

Hubbert’s prediction turned out to be remarkably accurate. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), U.S. conventional crude oil production peaked in 1970 at 9.6 million barrels per day and started to decline thereafter. But American oil consumption continued to rise following what looked like an exponential curve.

The ever-widening deficit between domestic production and consumption was filled with imported oil, which made up 35 percent of the American oil supply by 1973. Meanwhile, few Americans thought about how postwar suburban expansion was locking homeowners into a car-dependent lifestyle. According to the Federal Highway Administration, during World War II Americans had owned one car for every 4 or 5 people, or approximately one per family; by 1973 there was one car for every 1.7 people, or almost one for every adult in the country.

Then, in 1973, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), mostly located in the Middle East, placed an embargo on selling oil to the United States because of American involvement in the Yom Kippur War. While Arab oil did make it to America through third-party countries, the immediate effect of the embargo was to quadruple the price of crude oil, from $3 per barrel in September 1973 to $12 per barrel that December, as Karen R. Merrill records in her 2007 book The Oil Crisis of 1973-1974.

While there were indeed supply constraints, the “crisis” was worsened by panic. Afraid of running out of gas, drivers sat in lengthy lines at gas stations for hours, only to spend less than a dollar to top off their tanks. As Meg Jacobs argues in her 2016 book Panic at the Pump, this hoarding behavior exacerbated the shortage.

“We are running out of energy today because our economy has grown enormously and because in prosperity what were once considered luxuries are now considered necessities,” President Richard Nixon warned in a 1973 address titled “The Energy Emergency.” “Now, our growing demands have bumped up against the limits of available supply, and until we provide new sources of energy for tomorrow, we must be prepared to tighten our belts today.” To solve this crisis, Nixon set a goal of attaining energy independence by 1980 through a combination of energy conservation and development of alternative domestic energy resources.

But little was actually done to lessen American dependence on foreign oil. According to the EIA, petroleum consumption dropped from 17.3 million barrels a day in 1973 to 16.3 million barrels per day in 1975, but it climbed back up the unprecedentedly high level of 18.8 million barrels per day in 1978. Meanwhile, domestic oil production continued to decline; by 1979, 42 percent of the oil consumed by Americans was imported.

Then came a second oil crisis in 1979. The Iranian Revolution again caused oil prices to shoot up, and once again panicking drivers wasted more gas idling in lines at gas stations than they ended up buying once they finally got to the pump. President Jimmy Carter urged Americans to conserve energy. “We simply must balance our demand for energy with our rapidly shrinking resources,” he urged in an April 1977 speech titled “The Energy Problem.”

The Carter administration dropped the speed limit on interstate highways to 55 miles per hour and told people to turn down their thermostats to 68 degrees to conserve energy. Meanwhile, the federal government promoted the development of all kinds of alternative energy — including ethanol.

Ethanol in the 1970s and 1980s

Interest in ethanol exploded in the late 1970s and early 1980s, with dozens of books, articles and government bulletins published on the topic. Some of the earliest efforts were focused on small-scale ethanol production directly on the farms where corn was grown, reviving the 1930s dream that the farmer could be “energy self-sufficient” and power his tractors with home-fermented fuel. Energy security was the main argument for on-farm ethanol production in the U.S. National Alcohol Fuels Commission’s 1980 pamphlet Fuel Alcohol on the Farm.

But making home-grown ethanol wasn’t quite as easy as some of its boosters claimed. “Crash programs such as promoting and providing incentives for the construction of ‘a still on every farm’ will probably do just that — crash,” Donald Hertzman and others predicted in a December 1980 article for the American Journal of Agricultural Economics. “Farmers who have the grain for alcohol feedstock and the livestock for feeding the byproducts generally do not have the time nor technical expertise to run an alcohol plant seven days a week the year around.”

A more practical suggestion was to manufacture corn ethanol at large, centralized refineries and to mix 10 percent ethanol with 90 percent gasoline to form “gasohol,” which could be used in existing automobile engines without modification. The U.S. National Alcohol Fuels Commission calculated in their 1981 book Fuel Alcohol that “ethanol production can be increased to 25 to 30 times present levels using livestock feed corn as a raw material with only minor inflationary effects on U.S. food prices.”

Only corn ethanol was economically and practically feasible to produce on a large scale in 1980, but the commission expected advances in cellulosic ethanol technology to eventually greatly increase the amount of ethanol that could be produced. The popular media endorsed gasohol as a more palatable alternative than curtailing individual consumption; it seemed like a relatively painless way to lessen dependence on foreign oil without threatening the American way of life.

But gasohol had its detractors, too. Some people argued that corn production also had negative environmental impacts, or that ethanol might increase air pollution. Ethanol proponents argued that the environmental impacts of corn farming were much lower than those of oil drilling and refining. Ethanol was also the least toxic alternative available to replace recently banned tetraethyl lead in gasoline.

The strongest argument against ethanol in the middle of an energy crisis was also the hardest to refute. This was the question of “energy balance” or “net energy value.” Critics pointed out that corn production was highly fossil-fuel intensive, as was the process of transporting corn to an ethanol plant and converting it to ethanol. The million-dollar question was whether more energy was used to manufacture ethanol than was gained by burning it, and the results of early studies were not encouraging. Some showed that ethanol production was a net energy loss; others that it was neutral; and the most optimistic showed only small energy gains.

Ethanol proponents argued that it wasn’t the total energy used to manufacture ethanol that mattered, only the amount of scarce petroleum. If ethanol plants were powered by coal or even natural gas, converting these domestic energy sources into high-quality liquid fuels would still help lessen American dependence on imported oil.

End of the Crisis

The number of publications about ethanol sharply declined in the mid-1980s. Part of the reason was that the Reagan administration cut funding to Carter’s alternative energy programs — which was not necessarily bad for the environment since the majority of funds were supposed to go to extremely polluting fossil fuel technologies like coal-to-gas or kerogen (oil shale) extraction. Even the U.S. National Alcohol Fuels Commission had suggested putting more effort into making methanol from coal than ethanol from corn.

More significantly, the oil crisis ended, largely due to economics. Programs started by Carter and continued by Reagan removed long-standing government oil price controls, putting oil on the free market for the first time since 1959. Caleb Wellum argues in his 2017 University of Toronto Ph.D. dissertation, “Energizing the Right,” that oil futures trading on a global market lessened the power of OPEC or any single nation to disproportionately affect oil prices or cut off oil exports to a single country.

But the free market couldn’t reverse the decline of U.S. oil production. By 2005, the United States was importing 62 percent of the petroleum it consumed, and energy independence seemed farther away than ever.

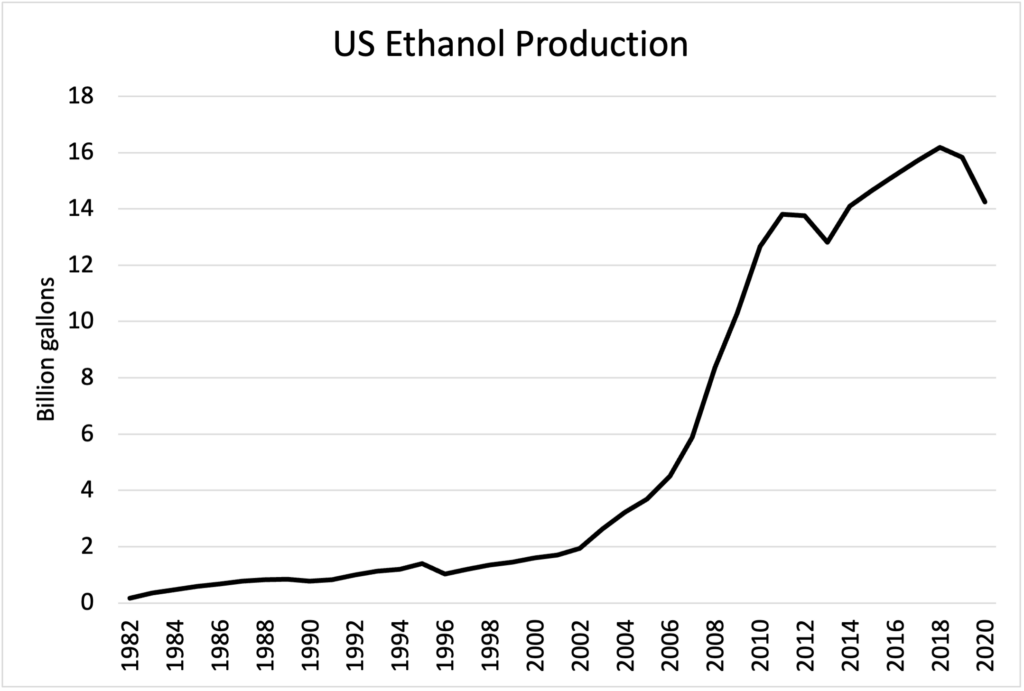

Yet it would be a mistake to assume that all progress in renewable energy stalled after the Reagan administration took over. Quietly but steadily, U.S. ethanol production increased from a mere 177 million gallons in 1982 to 3.7 billion gallons in 2005. By 2016, ethanol production was up to 15 billion gallons, and “gasohol” had completely replaced regular gasoline.

Looking back, it seems that both the highest hopes and deepest fears about ethanol have failed to materialize. Ethanol did briefly boost corn prices between 2007 and 2012 — but failed to be a panacea for agriculture’s economic ills. Corn farming does have negative environmental impacts — like soil erosion and nutrient pollution of surface and groundwater — but those impacts have not necessarily increased at the same rate as ethanol production.

And what about the hopes of R. C. Farmer and others that ethanol could eventually replace petroleum with clean, renewable energy?

The good news is that, ever since 2010, the United States has produced over 1,000 barrels of biofuels (including ethanol) per day — which would have completely satisfied domestic demand back in 1919!

The bad news is that U.S. oil consumption has increased 20 times in the past hundred years, and all of those biofuels only supplied 5 percent of total petroleum demand in 2020. It is physically impossible to grow enough biomass to replace all of the petroleum required to fuel the current American transportation system.

Most people agree that we will need to transition to all-renewable energy at some point in the future, whether voluntarily as part of climate change mitigation efforts or involuntarily because of declining fossil fuel reserves. But as the story of ethanol shows, that transition might be a lot harder than we think.

Anneliese Abbot is a graduate student in the Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. She is the author of Malabar Farm: Louis Bromfield, Friends of the Land, and the Rise of Sustainable Agriculture. She can be contacted at amabbott@wisc.edu.