Researcher Joe Lewis and researcher/farmer Alton Walker discuss how to harness nature’s built-in mechanisms to keep pests in check in order to successfully grow healthy crops

This is a joint interview with entomologist Joe Lewis and entomologist/farmer Alton Walker. Lewis spent his career as a Ph.D. researching parasitic wasps and how to restore ecological balance in cotton fields with USDA in Georgia, and he is the author of A New Farm Language: How a Sharecropper’s Son Discovered a World of Talking Plants, Smart Insects, and Natural Solutions. Walker, who also has a Ph.D. in entomology, farmed 600 acres of cotton and other crops south of Augusta, Georgia, from the 1990s until a few years ago. Lewis and Walker went to school together at Mississippi State in the 1960s and collaborated on research for several decades. Interviewing them together provides an opportunity, we hope, to see how ecological principles are put into practice; Walker’s story of his farming career is included in the text boxes.

Acres U.S.A. For those who haven’t read your book, could you give us a brief overview of your background?

Lewis. I come primarily from the research side. I had a full career working on beneficial insects, plant-pest relationships, and pest management. I started my career about the time Rachel Carson wrote her book, Silent Spring, which exposed the harms of the pesticide DDT.

Going back a bit further, though, when the industrial revolution came about, humankind began to lose our appreciation of the built-in strengths of living systems. I think it’s important to step back and realize that our entire universe and all that’s associated with it is made up of systems within systems. When you’re dealing with the health of those different systems, you have to think in terms of a full system. Since the industrial revolution we’ve had a lot of inventions that were spectacular, but we’ve tended to lose our appreciation for the power within the system.

An example of this was DDT for pest control. When it was discovered at the time of World War II, it was so spectacular as a control agent for different pests. It solved a lot of problems with mosquitoes and helped control malaria and other pests that attacked different plants. Just a small amount was miraculous. It really reduced human suffering. But we moved almost completely into the use of pesticides as the way to control pests, rather than to build up the built-in mechanisms that already existed to control them. It’s very important to know that in all these situations where you have a pest or an infection, nature does have a built-in mechanism to control it. There are beneficial insects and other built-in mechanisms within cropping systems that help prevent a pest like the cotton bollworm from being a pest.

The same thing happened with penicillin in the field of healthcare. Penicillin and pain killers were so miraculous that we starting using these interventions to control the problem. That’s become the universal approach. I think that humankind began to think that it was easy to control any undesired variable, like infections and pain and pests, by just using something that came in a bottle. We lost our understanding built-in systems.

Acres U.S.A. Our ecological understanding of things.

Lewis. Yes. The solution is within the system.

Acres U.S.A. Where were you doing your research?

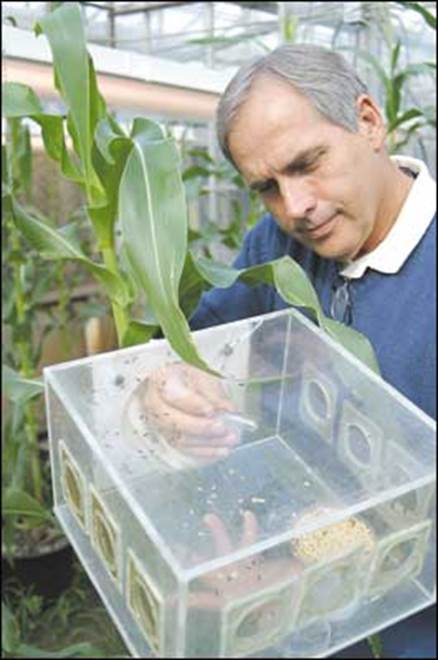

Lewis. I ended up in Tifton, Georgia, as a research scientist at the University of Georgia campus there, but associated with USDA, and I was working on how to improve our use of biological controls as a system for managing pests.

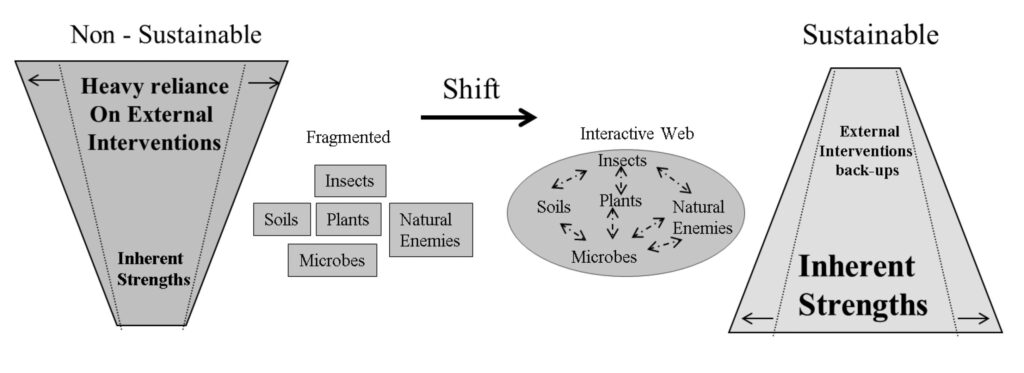

I was starting to understand the idea of using natural enemies to control pests, but the prevalent view at that time was that we could apply these beneficial insects like a pesticide, and that would reduce the use of toxic chemicals. But I started to realize that when you started intervening into living agricultural ecosystems by using pesticides, the problem wasn’t just that there was pesticide residue; there a lot of other problems. You disrupted the balance of the system. The beneficial insects that we produced in the lab weren’t the same. We found out that beneficial parasitic wasps, when we mass produced them in the lab and released them into the field, weren’t the same creature. The wasps in the lab, reared on an artificial diet — different from what an actual crop field — didn’t learn the same way as parasitic wasps reared in the field. We often have too much of a reductionist view.

I was studying the use of beneficial insects like parasitic insects and other predators like the lady beetle — natural enemies of pests like the cotton bollworm. At the time we had no understanding of how spectacular these natural predators were and how they had to interact as a part of the system of that web in order to make them work. But the idea of producing thousands of them and using them like a biopesticide that wouldn’t be poisonous or toxic to the environment — that was the predominant vision of the future. That was just using the same mechanisms of intervention from outside the system. But we started to realize that we had to work together — soil scientists, plant scientists, and biological controls, all together as a whole system. We were using too much pesticide and too much fertilizer. It was an intervention treadmill.

We have to stop looking for these spectacular interventions from outside. That really does more harm than good. The solution becomes a problem.

Acres U.S.A. Can you give us some background about how you got into cotton production?

Alton Walker. My undergrad degree was in forestry, and then I had a master’s in ecology from Mississippi State, and my Ph.D. was from Clemson in forest entomology. That was very significant in my thinking throughout the years because we had to control insects in our forestland without using pesticides. The economics did not permit the use of pesticides for forest insect control, so we had to find natural ways of doing it. That had a great influence on me. Even though I’m an entomologist by profession, I’m an ecologist at heart.

I was in the agricultural consulting business for about 15 years before I began to see the problem that was developing in the system. In the area where I was working, about a third of the land was taken out of agriculture and put into pine trees. There were a few reasons for this. One was soil erosion. With our large equipment we had plowed down our terraces, and the soil erosion was just unbelievable. I’ve seen washes in the field where I could just turn my truck around and never get outside the wash. This just destroyed the productivity of the land. And then pest resistance came along. There were ever-increasing costs to production. The system wasn’t sustainable. It wasn’t good for America. We had to find another way.

The farm I was raised on in Mississippi had 120 acres of productive farmland. We used very little fertilizer, almost no insecticides and no herbicides, and we had almost no soil erosion. The terraces are still there that my granddaddy put in. I look back at how productive that system was, and then I look back at when I was at Clemson taking a plant ecology and taxonomy course, and we went and looked an old forest land — with trees more than a hundred years old — and we collected all these insect pests that were there. There were literally hundreds of insects that were potential pests on the trees there, but they never became pests because there were no disruptions in the system. Potential pests were still there, but they were there at a sub-pest level.

I realized we needed to find a way to do this in agriculture — to bring nature back to agriculture. So, I met with Joe, and he told me a lot about what we needed to do to bring this back. Very soon thereafter we were involved in a small field research project where we compared the beneficial insects in a cover crop field with those in non-cover-crop fields. This was after the eradication of the boll weevil in the early 1990s. When the boll weevil was there, it was necessary to spray every year because it had very few enemies. But after the eradication of boll weevil, there was nothing out there that we were going to have to spray for.

That research project convinced me that we could grow cotton without using insecticides. So, I met with Joe again, and we knew that we had to perennialize the system — we had to keep plants growing in the system year-round to provide something for potential insect pests to feed on. We needed the balance of nature to come in. We knew we couldn’t do that with just one or two plants. We had to diversify the system and keep something growing year-round.

Those are the two main things behind our system of controlling insects. To do this, we had to look at what nature had done. It had already set out the system to keep the potential pests from being dominant; we just had to find a way to employ it in our system.

I’ll tell you that the system I used was not perfect. We still had to use some pesticides. We had to monitor the crop just like we did in the old days, to find out when the pesticide was necessary. But we were using the forces of nature as our primary control against insects. Pesticide was a backup.

We looked around for what cover crops were available to us, and we realized that crimson clover was a good one — most cotton pests feed on it. If we could get them feeding on the crimson clover, then the beneficials that feed on them could build up. It also turned out that crimson clover is a very good host for root knot nematode, which is another major problem in cotton in our area. So, it offered us two great solutions for our problems. One was insect control — the year-round feeding of the insects on it —and the year-round feeding of the nematodes on the crimson clover.

Acres U.S.A. How did we get to this place, where we we’ve become so reductionistic in our thinking about agriculture?

Lewis. Farming is moving, like everything, down a similar path. We’ve moved away from small family farms, where you had an ecosystem, with a mixture of cattle and small fields of different crops — where you had diversity. We didn’t have these monoculture fields with huge tractors. This reductionist approach that we have is moving further away from an ecological system, toward one where you just overpower everything. If you’re going to be a specialist in growing cotton, you grow cotton. If you’re a specialist in corn in the Midwest, you just grow acres of that. And we protect it by hammering everything else out, because we have all these miraculous pesticides.

By the late ’80s, we realized that the boll weevil was going to be eradicated — we could see that was coming. The eradication of the boll weevil doesn’t fit some of these principles we’re talking about because it was an invasive species — it didn’t have natural enemies — and for a while it was a tremendous pest problem. But once it was gone, we realized we could basically manage the other pests by built-in mechanisms.

We realized that there were several principles we were going to have to get back to. One was that we had to perennialize the system. We needed cover crops in the system. But it wasn’t just the cover crops — originally the interest in cover crops was to prevent erosion by keeping some residue in the soil. We realized they were much more important than that, though.

The point we were making was to practice something much more holistic — to not just think about how to solve an insect pest problem but how to farm in a sustainable system, leveraging all these attributes of interactions. We were uncovering things that showed just how powerful those built-in powers were.

Acres U.S.A. What other cover crops were you trying when you started growing cotton?

Walker. We eradicated the boll weevil from Georgia in about 1990, and I planted my first cotton crop in about 1995.

We were only looking at crimson clover as an applied cover crop, and that sounds like a monoculture, but it wasn’t. We had other things growing in the field — henbit, chickweed, cutleaf evening primrose, Carolina geranium, wild mustard — all of these were very good hosts for pests on cotton. By building these up, we could get build-up of beneficials.

Acres U.S.A. And did you terminate those before you planted cotton?

Walker. We wanted to have something growing on the ground 365 days of the year. So, we killed a 19-inch strip where we were going to plant, and we kept the other 19-inch strip growing. We killed it out with Roundup or Diuron, about two or three weeks before planting. And then I subsoiled using pneumatic tires, which sealed the trench back over, and then we planted. When I planted, I did use Temik — aldicarb — an insecticide for thrip control on cotton. We always put in some test strips leaving the Temik off. It’s a very toxic material, but the way we used it was safe because we put it in the ground as a dry granule. After a few years I determined I didn’t need the Temik.

The conventional model is a cradle-to-grave insecticide program, though. Spraying is automatic. That’s by and large what all my neighbors were doing. And in fact, in wet years they got a little better control of thrips than I did. Temik had to have water to dissolve it and to be taken up by the plant, so in dry years I got much better control than they did.

Lewis. They didn’t really worry about hitting an economic threshold before spraying; it was just automatic to put on something to stop the pests that normally occurred at any time of the year. It was just a blanket, automatic system.

Walker. Since then, Temik has been taken off the market. But it has been mostly replaced by a product called imidacloprid, which is similar to DDT in that it has a very long residual action in the soil.

In the first three years that I farmed, I used no insecticide except Temik at planting. But other growers in the area were putting on two to three applications of insecticide for bollworms and sucking insects. I had virtually eliminated the use of over-the-top insecticide.

But then, after three years, I could no longer get non-Bt cotton. I had to use Bt cotton. And then I had to start putting on one or two applications of insecticide for stink bugs. My neighbors were putting on at least three applications for that, so I was getting some reduction in use because of my cover crops and other practices.

Acres U.S.A. You would think the Bt traits would help with insects — but instead you started to need to use more insecticide?

Walker. That’s right. Bt was sold to us as a product that would not be harmful to our beneficials. And it’s not directly harmful to the beneficials. But because of Bt, you have no insects feeding on the cotton plants. It’s just like spraying the cotton plant seven days a week, 24 hours a day. You always have insecticide out there.

Lewis. The boll weevil was the primary pest, but once you treated for weevils, you woke up those big dogs. When I was a youngster, I’d walk along this country road where I grew up, and I’d see a big old dog sitting on the doorstep who was asleep. I’d think, “I can walk by that house quietly without waking that dog up,” but while I was passing by, the neighbor’s little dog would come running out there, barking and yapping. The little dog couldn’t harm me, but he could wake up that big dog.

And that’s the problem. Bollworm is typically not a pest, but once you had weevil in the system, you’d have to spray for it because it was an invasive species without natural enemies. Once you sprayed for the weevil, though, you triggered all these things, from aphids to spider mites — and the bollworm in particular, which was really hard to kill once you kill the natural enemies that disrupt them.

That’s what we saw coming — the boll weevil was eradicated, and we knew we could control everything else without pesticides. But the conventional programs thought they were going to solve that problem with the use of Bt cotton. There were a few years before Bt cotton came in that we didn’t hardly need any treatments because we didn’t have the stink bug. The conventional folks gave the credit to Bt for no longer needing to spray for bollworm — but that wasn’t it. We didn’t have any problem between the eradication of the weevil and the advent of the stinkbug issue. We didn’t have any need for Bt. The only treatment you should need in cotton now is for stink bug. Stink bug isn’t a new pest — it’s just a pest that was created with the use of Bt cotton because it upset the natural balance.

Acres U.S.A. So how did you deal with stink bug?

Walker. My clients were putting on about two applications a year on cotton after boll weevil eradication. I was not putting on any, so when the stink bug came along, I treated with two applications of pyrethroid. Pyrethroid is environmentally safer than organophosphates — it’s a man-made pesticide similar to pyrethrum, which comes from chrysanthemum flowers. The conventional organophosphates are very toxic.

In the early 2000s, the term “soil health” began to appear. I ignored it at first — being an entomologist, I thought I didn’t need to know anything about soil health! But then I realized that my soil health wasn’t great — even with the limited cover crop of crimson clover and the other plants that came up. Sub-soiling and plowing up of peanuts were undoing a lot of that. It’s been shown that digging up peanut reduces organic matter by half a percent each time you do it. After 20 years of cover cropping with just crimson clover, I only had about a half to 1 percent organic matter.

So, I diversified my cover crop. I put in ryegrass, another variety of clover, and some kale. I also went to no-till. And with that, things began to improve rapidly. I started that in 2014, and for the next four years I only put on a half to one application of insecticide for stink bugs each year. Then, the last four years I farmed, I only put on one and a half applications total. And of course, we weren’t using any Temik. I was only putting on 10 or 15 percent of what my neighbors were putting on.

I realized that my insect control did not all come from beneficial insects, as I had thought it would. Some of the control came about because of soil health. A healthier plant can turn on defensive mechanisms against these pests. We know very little about how this works, but we know plants can transmit information through mycorrhizae, or even through the air, to other plants, to tell them to turn on their defenses. We had known for a long time that healthy cotton plants were not as susceptible to nematodes. But we didn’t know the plant turned on defenses until recently — about in the ’80s at least.

Our insect control was quite good, but the greatest cost savings was in nematode control. In the 25-plus years that I farmed cotton using this system, I never once saw any problems with root knot nematode. Part of this comes from the fact that we had a year-round supply of food for the nematode from the crimson clover and the cotton plant, so we had year-round beneficials. But also, like I mentioned earlier, the plant could turn on its defenses against the nematodes. We had bacteria and fungi encasing the roots of the plants, physically preventing the nematode from entering the roots.

In terms of weed control, we were not quite as well off. We had more fungi, bacteria, insects, and birds feeding on the seed of these weeds. This reduced the seed bank. We also had the shade from our crop residue and from the cover crop, which prevented lots of weeds from emerging. But I still had to use quite a few herbicides. We reduced the herbicide used by 30 to 50 percent, depending on the year.

The last two years that I farmed, I reduced my fertilizer input by 75 percent. We only put chicken litter on our sandier soil. For nitrogen, I applied 15 units of urea over the top of the plant. The only reason I did that was that I was just afraid I didn’t have enough nitrogen. I had no way of knowing; that may or may not have been needed.

Acres U.S.A. I imagine cutting all these applications made your operation more profitable.

Walker. We reduced the cost of production by 30 to 40 percent, and we increased production by 15 percent over my neighbors right across the road.

We also had no erosion — that’s another pest. We controlled it nearly 100%.

What surprised me more than anything else is that the same system that is good for insect control is also good for the entire production system, and it will eliminate just about all the problems associated with the conventional system we have today — economic problems, pollution, environmental problems, etc. We can store lots of carbon in our soil to help with earth warming. But most of all, I think, the food quality will improve, which would improve the health of our nation.

Acres U.S.A. It’s fascinating how there’s this interaction of populations between the three “pests” — the boll weevil, bollworm and stink bug — and I’m sure others. They all balance out in systems that mimic natural environments — at least the native species.

Lewis. Alton and I, and others, realized that after eradicating the boll weevil, if we didn’t take the opportunity to move to a full ecologically based system, we were missing the opportunity of our whole generation.

We had Bt cotton coming in, and we already knew they weren’t doing it in an ecological way. We were going to be in a situation where every crop was going to have pesticide sprayed from inside out, on the entire plant, 24 hours a day — and that was going to create some problems. They wanted to use the full force of pesticides all the time against the bollworm, which they wanted to eradicate. The idea was that we’d gotten rid of the weevil, and now we’d use Bt to eliminate the bollworm problem.

When you don’t have Bt, and you have feeding activity by bollworms in the field, that stimulates the plant to start producing some nasty chemicals, in addition to the odors that they produce to recruit beneficial insects. Those nasty chemicals helps prevent the stink bug. It has a cross interaction. Not only does it slow down the boll worm — it prevents the stink bug from breaking in.

But we are losing that attribute. Bt doesn’t reduce the amount of pesticides conventional farmers have to spray.

Acres U.S.A. What kinds of challenges did you encounter in this alternate, more ecological cotton system?

Walker. I did have to replant lots of cotton. Probably 25 percent of my cotton had to be replanted over the years because of seedling disease. Just in the last year before I stopped farming, I read something saying that if you killed your clover two weeks before you planted, you wouldn’t have that problem with seedling disease. So that year I killed the cover crop about four weeks before I planted, so the plants were dead two weeks before I planted, and I had no problem with seeding diseases.

We also had challenges with grasshoppers about one year in four — the dry years. Grasshoppers favor dry weather. Those years I had to treat very early, right after the cotton emerged. I used pyrethroid for that. One application did the job.

The other problem with no-till was getting good seed-to-soil contact. I had to modify my planter, putting in a spiked closing wheel and a V closing wheel behind that. And sometimes we didn’t get a good tap root. One year I made real good cotton, but the wind came along and blew all my cotton over, and I couldn’t pick it. We solved that problem by putting a toolbar ahead of the planter toolbar and putting a 20-inch coulter in. We weighted that toolbar with 1,500 pounds of metal on the six rows. This coulter ran about eight inches deep, and I never had any more problems with not having a tap root.

Bollworm and other pests came out in March in our area — Burke County, Georgia, south of Augusta — and began feeding on our plants. That gave us three months before they would become a pest on cotton. It gave us three months for the beneficials to build up. If you get further north of us, they won’t have this time, so they may have a problem with this system. After a few years, I think the system will get in balance and take care of that problem, but that’s just my speculation.

If we included livestock in this system, the economics and the biology of the system would improve greatly. That’s what we had when white men came here — we had grazing animals, rabbits and birds and buffalo and deer, and they were fertilizing the soil. One grower I worked with on this system had cattle on one irrigated field in the winter, and he also had five or six other irrigated fields where he had no cattle, and the organic matter rose two-and-a-half times as fast with cows grazing in the wintertime. This just adds to the diversity of the system.

Acres U.S.A. And why did you stop farming?

Walker. Well, I was sitting on the cotton picker and had a massive stroke. My neighbor picked my cotton that year, but that ended my farming days. If that had not happened, I would probably still be working with the system.

Acres U.S.A. Can you talk a little bit more about plant signaling? I know some of your original work was about how plants signal to beneficial insects.

Lewis. We realize now that what we reported beginning several decades ago — which we thought was so spectacular — is just the tip of the iceberg. The power of different defensive mechanisms and the interactions of all these different components is just miraculous.

Our original vision was to identify these chemicals that help attract parasitic insects. We knew something was taking place, but we didn’t know what it was, nor the behavioral mechanisms associated with it. We had two approaches — one, which is very similar to today’s conventional mindset, was to identify these chemicals that draw the natural enemies and spray them on fields to pull in a lot of natural enemies. But then we realized that that would be disrupting the natural system. The chemicals would be going where there weren’t any pests.

Our other approach was to mass rear the natural enemy and release them in fields. We ended up finding out that when you do that, they just leave the field, because they are not in the behavioral mechanism that they are when they’re working so powerfully.

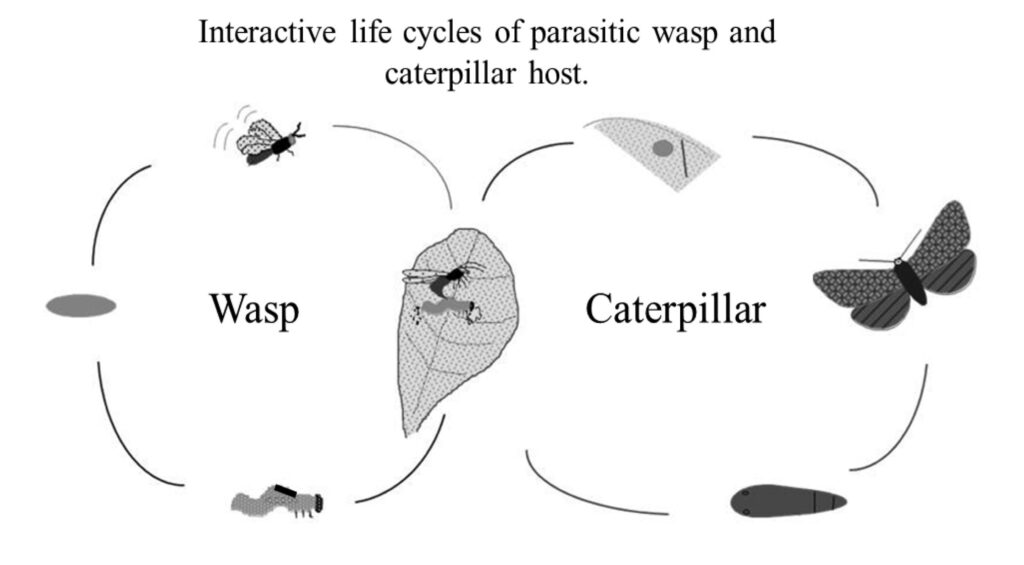

What we found out is occurring is that when the herbivore begins to munch on a plant in any way, the plant recognizes it’s under attack, and it does that by recognizing a chemical in the salivary secretions of the pest that tells them, “This pest is on me.” And then it cranks up a set of chemical factors inside that begin to emit body odors. It involves about six to 10 different chemicals. It’s like a barcode; the blend is unique for each different pest. They make these odors that recruit the beneficial predators.

We found out that this chemical in the salivary secretions of the caterpillar is an elicitor. The beneficial insect not only knows something’s feeding on this plant; it knows what type of pest it is. You can see the value of that, because there’s several different kind of pests at any time. There’s aphids, there’s spider mites, there’s boll worms, and there’s different kinds of beneficial insects that are attacking. If they couldn’t tell the difference, they would be going to plants by mistake.

This is a unique system — the plants are talking to the good guys and telling them “something’s feeding on me” — as well as what caterpillar it is, in order to attract the right beneficial. It’s a powerful system.

Walker. There are a lot of things that can turn this ability to sense and signal on or off in the plant. We know that certain insecticides will shut this down in the plant. The organophosphates just about shut it down. And then I have seen where we had too much nitrogen on cotton — that shut it down. The cotton would get 10 times as many insects on it as the neighboring cotton. Or in dry weather, if the plant was stressed, it would attract more insects.

A healthier plant growing in a healthier environment is going to turn this mechanism on a lot more.

Lewis. Also, not knowing this mechanisms, we were not selecting for it in breeding. You can breed for a plant that does it strongly. We can also agronomically manage to optimize these mechanisms. We can do both.

For example, we found out that some of the wild cotton that has escaped — it grows in different places in Florida as a little tree — some have tenfold the ability to emit these defense signals that recent agronomic cultivars do.

Acres U.S.A. I think one of the things that people might push back against is that if you’ve got a couple-hundred-acre field, how are beneficial insects able to get to the middle of the field?

Walker. Beneficials are very mobile. They fly for miles. They can get there. And you brought up a good point. We’ve spent 75 years destroying the system — it may not come back in one year. It does take more than one year. It takes many years to build it back up. I had a field that was a hundred acres, and I had no problem with it.

Lewis. But that’s a good thing to consider when you’re redesigning a farming system — you build these factors in, and you leverage these built-in strengths. That’s what we need to understand.

These parasitic wasps are free living as adults. They use the caterpillar as a host to lay their eggs in. They have to have a nectar meal every now and then, and it turns out that the cotton plant has extra floral nectar under the leaf. We never really knew why that was. But that’s a very important food resource for the parasitic wasp. When plants are being fed on by a bollworm, an army worm, or whatever, the plant increases the flow of nectar, as well as producing the chemical signal to the wasp.

Acres U.S.A. How would you describe the difference between the system you’re describing and traditional integrated pest management?

Walker. Integrated “pest” management — that’s a misnomer if ever there was one. It’s integrated “pesticide” management. That’s all they’re trying to do.

Lewis. In IPM, they’re managing pesticides, not the pests. They count what’s out there and treat only when the threshold hits. But it’s just managing. They’re not choosing how to promote landscape ecology and the mechanisms that promote this system.

Walker. Like most other new inputs, it worked very well at first, and farmers did reduce their pesticide use quite a bit. But after a few years, with resistance, they were back putting out the same number of insecticide as before.

Lewis. We’ve had it backwards for a long time. The first meeting of the southeast branch of the Entomological Society of America I went to was in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1965, and almost every paper being presented was a new pesticide for this or that. That’s the way we manage pests — through pesticides.

Walker. What Joe and I, and others, are doing is trying to manage insect pests by keeping them there, year-round, at a sub-pest level — below the pest level. The pests are always there, but we are keeping them there at a level at which they are not pests.

Lewis. The question we always have to ask is, “Why is this pest a pest?” Because insects shouldn’t normally be pests. The fact that it’s a pest means something’s out of balance — unless it’s something like an invasive species. A pest outbreak of any kind tells you something’s wrong. Or, in some instances, you may be trying to grow something where it really doesn’t work.

Acres U.S.A. Have either of you ever experimented with boron applications for pest control?

Walker. We have boron deficiencies in both cotton and peanuts, and we do apply those, but not specifically for pesticide pest control.

Lewis. But you’ve talked to me about nitrogen, Alton — about how we use far more than what we need.

Walker. Yes, we’ve used more of that than we need. Since those crops are deficient in boron, we put it on to keep from stressing the plants, and no doubt balancing those nutrients will help reduce pests in the plant.

Another thing is that we learned not too long ago what Roundup does to the system. Roundup reacts with our metals; the main one it reacts with and prevents plants from utilizing is manganese. We treat peanuts two or three times every year with additional manganese. Now this is also a problem in the cotton, but it doesn’t exhibit itself — we don’t see the problem of the discoloration in cotton leaves that we see in peanut. But the heavy use of Roundup tied up nutrients in the soil. This also goes along with raising the pH to above 6.5; the two together has really hurt the uptake of manganese.

Lewis. We haven’t looked at any of this kind of stuff holistically. Historically, a plant agronomist would study that, but a pest management specialist wouldn’t. We break it down too much into specialties. The agronomist may be managing the cotton plant in a way that will produce another quarter of a bale per acre, but maybe the crop loses a half a bail trying to control the pest outbreak.

Walker. I think that once we get away from using pesticides and commercial fertilizers and we start to improve our soil help, we will not have to put on these specialty fertilizers like boron and manganese and whatever else. I think that the organisms will get these elements from the soil and move them to the plant roots and up the plants, and the plant will be able to balance themselves in the system.

Another great advantage of this system, I think, is for cattle production. One of the big problems in cattle production is putting up stores for the winter. That is a huge cost in cattle production. We can eliminate lots of this by grazing our animals on these fields in the wintertime. I truly believe that if we had a diversity of animals on a cotton farm, a farmer could make a very good living on 300 acres. I made a very good living on 650 acres without livestock. This could help bring the communities back together in rural America. This system doesn’t work with huge farms; it requires more intensive management.

Lewis. Agriculture has gone in the direction of centralization and specialization in modern times, which means bigger farms and more specialty areas. Small farms — that’s how we are going to redevelop these rural communities. We need to support small, diverse, family farmers. We aren’t going to fix rural America by building more four-lane highways into these areas. That’s the kind of thing we hear folks in our state government talking about in. But that’s not going to build community; that can only happen ecologically.

Acres U.S.A. It seems like when you drive on a highway, there are far fewer bugs on your windshield than there used to be. Is this just anecdotal, and how much of a concern should that be to us?

Lewis. I’ve seen a couple of studies on this. There’s some places where they’ve done indexing. But at least anecdotally, this reduction in insect numbers seems clear.

Walker. This is really a problem in a monocultural forestry system like I worked in. At least 80 percent of commercial forests are loblolly pine, and loblolly pine plantation is an ecological desert. There’s no spraying, but you get almost 100 percent shade — there’s almost no sunlight touch the ground. There are no other plants growing in a loblolly pine stand. There’s just the one species out there — almost no birds, no insects. We just have a few species that the modern system favors. Anytime you eliminate diversity, you favor some species.

Lewis. But also you favor upheaval and chaos. The way we farm is to clean till everything when we’re through with the cropping system, and throughout the winter there’s this eroding, empty field, and then we come in and plant around April to May, and we get explosive growth. There’s a lot of upheaval going on, and you don’t get equilibrium — you destroy it at the end of the year.

Doing this in so much acreage creates a chaotic environment. I think it really affects the abundance of different kinds of natural insects. We may create a sudden increase of some pest for a period of time. It’s just upheaval. It’s a very changing dynamic. We don’t get equilibrium.

Walker. We see this in birds too. We probably only have 25 percent of the birds species that I saw when I was a child. Especially in urban areas.

But this system I grew in works. It improves the quality of the crop, reduces pesticides and reduces erosion. Cotton is a unique crop. It’s struggling right now economically, and maybe it needs to struggle a bit more in order to change the system. If we got all the government subsidies out, the system would change immediately.

Lewis. Bt cotton, which covers so many acres throughout a cotton belt, is meant to suppress the bollworm and the tobacco budworm populations. But the beneficial insects that depend on them — two of the main ones we studied are specific to those two species of insects. Their populations are getting really reduced. I could see one of them possibly going extinct in the U.S. as a result of Bt cotton. We don’t think very much about just how much this kind of technology impacts our ecosystems.

Read more about Joe Lewis’s discoveries on ecological entomology in his book A New Farm Language: How a Sharecropper’s Son Discovered a World of Talking Plants, Smart Insects, and Natural Solutions, available at bookstore.acresusa.com.