Wheat (Adrian Sanchez-Gonzalez, Montana State University) — A wheat stem sample from a research plot near Amsterdam, Montana. Scientists there have confirmed what Dr. Joe Lewis found in cotton fields in Georgia 60 years ago see interview — that plants under attack send signals to parasitic insects, which help control the pests, and that providing habitat for these parasitoids is a simple ecological solution that eliminates the need for toxic pesticides.

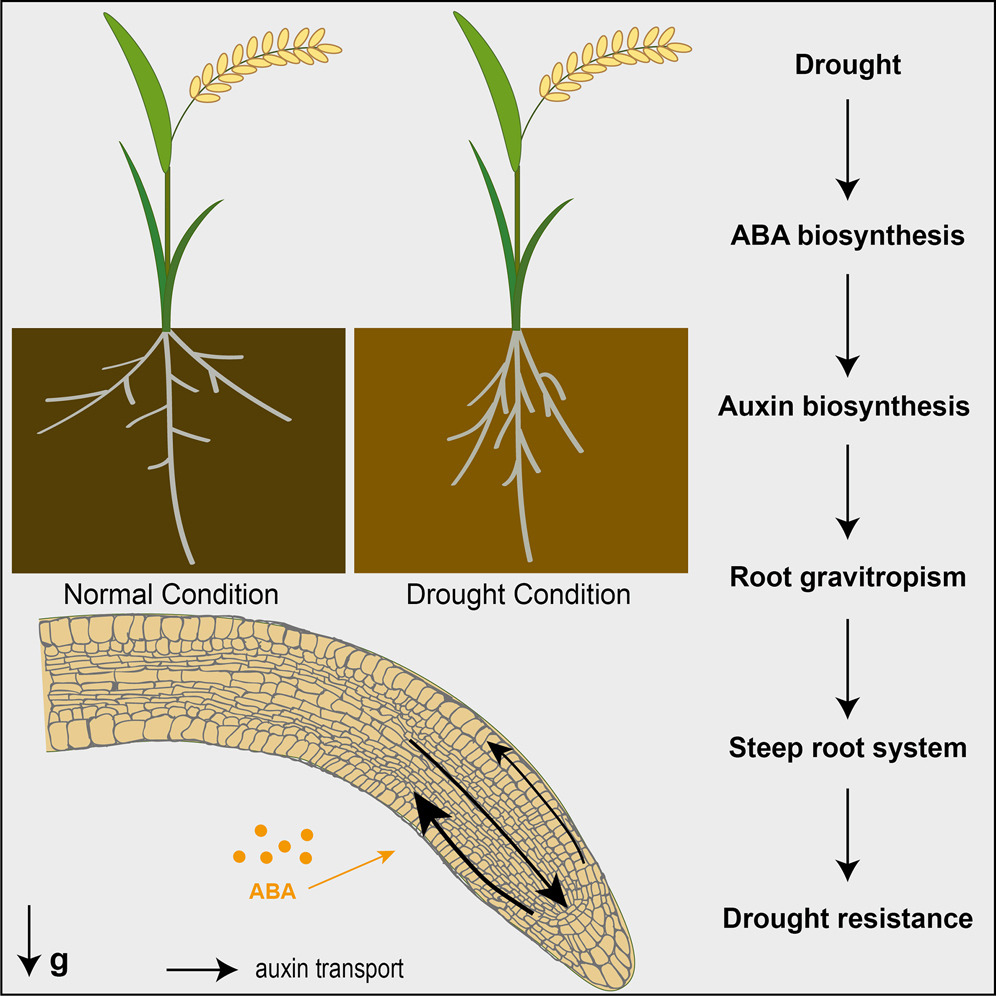

Roots (Current Biology) — Abscisic acid promotes the production of auxin, which enhances root gravitropism, allowing root to grow at steeper angles in response to drought.

Kale (Rose Albert, UC Davis) — A California quail walks among kale seedlings. A UC Davis study found that bird poop from small birds are unlikely to pose a food safety risk for growers.

Managing Wheat Stem Sawfly Ecologically

Wheat stem sawflies cost agricultural producers millions of dollars in losses each year; total losses in Montana alone for 2024 were estimated at $66 million.

To help control sawfly, Montana State doctoral student Jackson Strand examined the impact of smooth brome, a common grass in Montana, on sawfly populations in wheat. “There’s a strong demand for solutions other than pesticides — which don’t work for wheat stem sawfly — and finding a solution that’s sustainable for growers who may not have a lot of time or resources to do things like plant different crops,” said Strand of his research, which was recently published in the Journal of Economic Entomology. “We’re trying to figure out if smooth brome is beneficial and if we can help promote populations of parasitoids that otherwise sometimes fluctuate across seasons and regions.”

Parasitoids are insects that act as biocontrols. In the case of sawfly, they operate by paralyzing and then eating the sawfly larvae that feed inside wheat stems. Because parasitoids are native insects, they show potential as a natural management tool to mitigate damage. Strand found that if smooth brome is present near wheat fields, both the sawflies and the parasitoids may gravitate to it.

Through greenhouse experiments and laboratory analysis, Strand sought to identify why that might be by measuring and comparing the volatiles released by smooth brome and wheat. Volatiles are naturally occurring chemicals released by plants, increasing in intensity when they are under stress.

“The plants that were exposed to sawflies expressed different compounds than the ones that weren’t,” said Strand. “Smooth brome produces the same compounds as the wheat, but in higher quantities. The sawflies are triggering a stress response in the plant, and then the parasitoids are keying in on those compounds and finding their hosts.”

Smooth brome is not a native plant, but it is widespread around Montana, particularly near roadways, where it was once used to mitigate erosion. While intentionally planting brome isn’t recommended, fostering what already exists could provide an appealing alternative for sawflies, consequentially protecting nearby wheat crops.

Meanwhile, Montana State master’s student Lochlin Ermatinger has been exploring new ways to identify and predict sawfly infestation in the first place, publishing his results in the journal Remote Sensing.

Wheat stem sawflies spend most of their life cycle within the stem of a wheat plant, complicating their management because seeing their damage from the outside is much more difficult than with other pests.

Ermatinger collected satellite image data on three scales: spatial, spectral and temporal. By measuring the spectrum of light reflected by wheat fields across a large area and over time, then comparing that data with where sawfly infestation was confirmed through physical analysis of wheat stems, he built a model that could use small variations in reflected light to estimate infestation across an entire field.

“We’re able to estimate now, to a degree of statistical significance, what the infestation rate is,” Ermatinger said.

Further Evidence of Ecological Disease Control

Wood Ants and Their Associated Microbes Inhibit Plant Pathogenic Fungi

Researchers from Aarhus University have found that live ants, crushed ant extracts, and washed ant extracts effectively inhibit the growth of economically significant plant pathogens, such as apple brown rot. The researchers also observed wood ants transferring microorganisms to plant surfaces within seconds of contact. The dominant microorganisms isolated from the ants included four bacterial strains and one yeast. Two of the bacterial strains exhibited inhibitory effects against several plant pathogens, including apple scab, gray mold, and fusarium head blight. The study highlights the potential of wood ants and their microbial associates as environmentally friendly alternatives to chemical pesticides, with the inhibitory effects likely linked to antibiotic compounds produced by the ants’ microorganisms.

Plant Hormones Tell Roots to Access Deeper Soils in Search of Water

Scientists from the University of Nottingham have discovered how plants adapt their root systems in drought conditions to grow steeper into the soil to access deeper water reserves. They identified how abscisic acid (ABA), a plant hormone known for its role in drought response, along with the key hormone auxin, influences root growth angles in cereal crops such as rice and maize. The results have been published in Current Biology.

In drought conditions, water often depletes in the topsoil and remains accessible only in the deeper subsoil layers. The researchers discovered a new mechanism where ABA promotes the production of auxin, which enhances root gravitropism, allowing roots to grow at steeper angles in response to drought. Experiments showed that plants with genetic mutations that block ABA production had shallower root angles and weaker root bending response to gravity compared to normal plants. These defects were linked to lower auxin levels in their roots. By adding auxin externally, the researchers restored normal root growth in these mutants, showing that auxin is key to this process.

The findings were consistent across both rice and maize, suggesting that this mechanism could apply to other cereal crops as well.

Biochar Reduces the Risks of DDT-Contaminated Soil

DDT soil pollution is still a major problem in many parts of the world. Researchers have recently developed a new method to manage ecological risks from the toxin by binding it with biochar. When they mixed biochar into contaminated soil at a former tree nursery, DDT uptake by earthworms in the soil was halved. This method may enable the growing of certain crops on land that is currently considered unusable due to the environmental risks.

DDT has been linked to a variety of negative health effects in humans and animals, and it breaks down very slowly. It poses an ecological risk because it can be taken up by terrestrial organisms such as earthworms. When these are in turn eaten by birds and other animals, DDT begins to accumulate within the food chain, which means that the top predators are affected by the highest toxin concentrations.

Biochar — which is similar to charcoal — binds contaminants, can improve soil health, and can contribute to long-term storage of carbon in the soil. The article was published in the journal Science of the Total Environment.

Little Birds, Little Poops, Little Food Safety Risk

Since 2006, when an E. coli outbreak devastated the U.S. leafy greens industry, growers have been pressured to remove natural habitat to keep wildlife — and the foodborne pathogens they sometimes carry — from visiting crops. Growers are often advised not to harvest crops within a roughly three-foot radius of any wildlife feces, lest they risk failing a food safety audit or losing a buyer contract. Growers often cite such concerns as a barrier to implementing conservation actions they would otherwise consider taking on their farms.

Through field and greenhouse experiments, bird surveys, point counts and fecal transects, the authors assessed food-safety risks from nearly 10,000 birds across 29 lettuce farms on California’s Central Coast. They spent hours following turkeys, bluebirds and other wild birds at the UC Davis Student Farm and nearby Putah Creek, collecting hundreds of fecal samples. They compared E. coli survival in bird droppings on lettuce, soil and plastic mulch to measure pathogen persistence.

After all of these efforts, they landed on a simple finding: Smaller poops from smaller birds carry very low risk of foodborne pathogens, which were rare in birds overall. If a bird were to become infected, pathogen survival depends heavily on the bird’s size.

“Birds that are large produce really big feces, and that’s where pathogens are more likely to survive,” said lead author Austin Spence. “Birds that are small have tiny feces, and the pathogens die off quickly. So farmers don’t have to know the species of bird it came from. They just need to know the size. If it’s the size of a quarter, don’t harvest near that. If it’s a tiny white speck, it’s very low risk and probably fine.”

Beyond fecal size, what the birds pooped on — be it the crop, soil or plastic — made a difference for pathogen survival. In the study, E. coli survived longer on lettuce itself than on soil or plastic mulch.

Fortunately, about 90 percent of birds observed on the farms were small and tended to poop mostly on soil, where pathogens perish quickly. By avoiding no-harvest buffers when food-safety risks are low, growers of leafy greens could harvest about 10 percent more of their fields.

The study opens up new strategies for growers to better balance conservation and food-safety risks. For example, growers could erect nest boxes to attract small, beneficial insect-eating birds, like bluebirds and swallows, that help control pests without risking food safety. The work also contributes to a growing body of research that suggests growers do not need to remove habitat to improve food safety.

On Glyphosate — Straight from the Researchers

“Glyphosate exposure and GM seed rollout unequally reduced perinatal health,” PNAS, January 2025.

The advent of herbicide-tolerant genetically modified crops spurred rapid and widespread use of the herbicide glyphosate throughout US agriculture. In the two decades following GM-seeds’ introduction, the volume of glyphosate applied in the United States increased by more than 750%. Despite this breadth and scale, science and policy remain unresolved regarding the effects of glyphosate on human health. Our results suggest the introduction of GM seeds and glyphosate significantly reduced average birthweight and gestational length. While we find effects throughout the birthweight distribution, low expected-weight births experienced the largest reductions: Glyphosate’s birthweight effect for births in the lowest decile is 12 times larger than that in the highest decile. These estimates suggest that glyphosate exposure caused previously undocumented and unequal health costs for rural US communities over the last 20 years.

“Glyphosate exposure exacerbates neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology despite a 6-month recovery period in mice,” Journal of Neuroinflammation, December 2024.

We recently found that [mice] dosed with glyphosate for 14 days showed glyphosate and its major metabolite, AMPA, present in brain tissue, with corresponding increases in pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-⍺ (TNF-⍺) in the brain and peripheral blood plasma. Since TNF-⍺ is elevated in neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s Disease, in this study, we asked whether glyphosate exposure serves as an accelerant of Alzheimer’s pathogenesis…. We found that AMPA was detectable in the brains of [mice] despite the six-month recovery. Glyphosate-dosed [mice] showed reduced survival…. Notably, we found increased pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines persisting in [mice] brain tissue…. [O]ur results are the first to demonstrate that despite an extended recovery period, exposure to glyphosate elicits long-lasting pathological consequences.