Innovation merely requires a change of mindset

I grew up and still live close to a large Amish and Mennonite community, in which I have several friends and acquaintances. I find many of them very innovative and ones to think outside the box. Like a few in the “English” world, some are also true leaders in their community. When key individuals show that a new way of doing something can and will work, then others are more likely to follow. One of those individuals is my friend, Mr. G, who requests to remain anonymous.

Like several in the community, Mr. G multitasks — managing multiple enterprises, including farming, a major business, and of course some livestock. Mr. G has raised replacement dairy heifers, out and back into the cow/calf, and also has several horses, both draft and standardbreds. There has been a slight shift from a purely agrarian way of life in these communities to one that more likely now includes entrepreneurship or off-farm work. To many, this life seems very old-fashioned, but I will tell you that technology is very much alive and well from many standpoints.

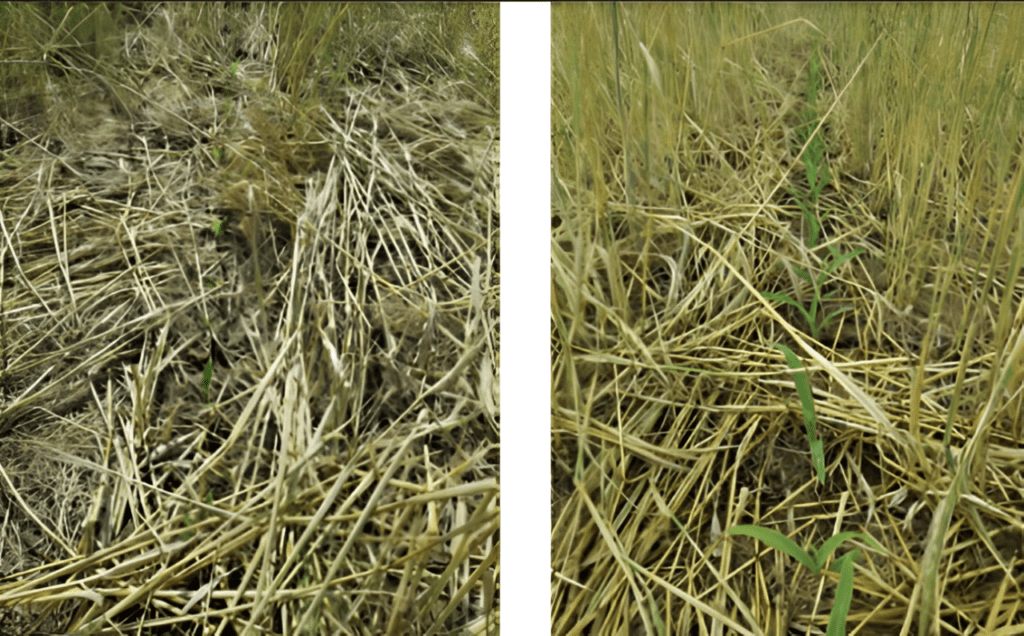

I was not surprised to find out that Mr. G was no-tilling corn and soybeans and was very environmentally conscious and conservation minded. I visited him last May while he and his son were planting corn. Lo and behold, they were planting green!

Planting “green” does not suggest that he was a newbie or was using a green implement — though he would quickly tell you that both were probably true. Planting “green” purely refers to no-till planting of primary crops into actively growing cover crops.

Mr. G explained that he had seen some cover crop fields get ahead of people. Too much rain prevented them from being able to terminate the cover crop as early as planned. If the opportunity to plant came to be, perhaps it would be better to plant, terminated or not, and get the crop in the ground.

He and his son discussed what to do a couple of years earlier when their first cereal rye cover crop had gotten ahead of them due to extended wet weather. It hadn’t reached maturity yet but was heading that way fast. “It cost us a little more nitrogen, but it also helped to take up some of the excess moisture that year, and we had better control of weeds than we have had. A mistake is evidence that you have tried,” quipped Mr. G. “We figured there had to be a better way to manage it.”

Terminating the cover crop after that planting would have been better if it had been sprayed earlier, if circumstances would have allowed it. This led to planting “green.”

Mr. G started using cover crops because they wanted to reduce erosion, improve water infiltration, and reduce weed pressure. The weeds that were slowly increasing in his fields included marestail and Palmer amaranth. They saw improvements in all three goals very quickly.

Cereal rye cover crops were then used after both corn and soybeans. The cover crop was broadcast seeded at 35 pounds per acre in early October of 2021, and the stalks were bushhogged on the corn ground. With sufficient rain soon after planting, the stand established quickly and provided good cover prior to winter. Corn is planted in 36-inch rows. This width is needed when running the equipment effectively with horses. It was planted at a population of about 29,700 on May 12. After planting, the field was sprayed with a single application combination of Sharpen, Roundup, and Lexar.

Approximately 50 pounds per acre of nitrogen was added at planting, along with some phosphorus and potassium in the typical 2 x 2 position. A total of 180 units of nitrogen were added, plus a three-ton fall surface application of composted turkey manure.

Mr. G has been practicing no-till for the last 25 years, but it was the addition of a new small farm that sparked the need to do more. The new farm had drainage issues, a lot of weed pressure, and quite a bit of compaction, along with a reduced amount of topsoil from long-term erosion issues. The benefit of no-till was not new knowledge for Mr. G and his son; the savings of time alone was a big factor for a busy family.

Mr. G realized that he needed to improve drainage, reduce erosion, reduce competition from increasing weeds, and improve the soil for long-term productivity. He and his son committed to sticking with only no-till on this new farm after doing some tile drainage and leveling. From attending meetings, reading articles, and talking to local advisors, they were convinced that they not only needed to eliminate all tillage but also work to build back soil organic matter and soil health. The strategy at that point was continuous no-till with a cover crop every year going forward.

The soil types on this new farm are all silt loams. It doesn’t take much exposure to the elements to have sheet and rill erosion on this type of soil, even with gentle slopes. Sheet erosion is often quite hard to see unless you look really closely, but it can add up quickly and do a lot of damage over time. “This type of erosion had to be addressed,” Mr. G said. “Not only are we losing precious topsoil, but we are also losing fertility, and it’s leaving the farm and moving downstream.”

Mr. G realized more than two decades ago that erosion had to be controlled and that traditional farming techniques were just not going to work. Conventional tillage was not only very time-consuming, but it was also costing the farm money from the loss of soil, nutrients, and production.

Though Mr. G had used cover crops occasionally in the past, before finally owning some spraying equipment, the timing of termination was a problem — especially a delayed termination of annual ryegrass one year. After purchasing his own spraying equipment, the primary timing concern still present was he and his family walking through a pre-sprayed field and consumption of any sprayed forage by his horses.

Mr. G’s son remarked more than once while planting the corn into the green cereal rye cover crop that the horses were not eating much hay in the evening after a hard day of pulling the planter. With his initial focus on the planter, planting depth, and the like, he didn’t notice how much cereal rye was being consumed every time they stopped — he was glad it was chemical-free!

Mr. G utilizes a John Deere 7000 planter with a three-quarter-inch fluted coulter for cutting through the green cereal rye. The weight of the planter is usually sufficient to easily slice through the green material. He used to rely on his Yetter row cleaners, but since he started planting green, he finds them unnecessary. However, he occasionally needs them on other fields not planted green.

During the wet spring of 2022, Mr. G was initially concerned about soil conditions for planting. However, the actively growing cereal rye was still taking up moisture, and with a few sunny days, the soil conditions turned out to be excellent. Even my pocketknife penetrated the topsoil easily, with minimal smearing, indicating optimal planting conditions.

Over the last eight years, Mr. G has implemented continuous no-till and cover crops on his farm. He believes in the philosophy of helping others and acting on the advice he gives. He has spoken at local meetings and field days to promote the benefits of no-till and cover crops. While he hasn’t quantified the changes since the first year, it’s evident that soil organic matter has increased, soil structure has improved, water infiltration has increased, and compaction has decreased.

At the end of the 2022 season, I had the opportunity to join Mr. G and his son during corn harvest on the new farm. Yields were impressive, with significant portions of the field yielding 240 bushels per acre. As we harvested corn with a horse-drawn two-row corn sheller, the experience was tranquil and reminiscent of a bygone era.

Looking ahead, Mr. G plans to explore incorporating wheat into the rotation, followed by an annual forage crop instead of double-crop soybeans. He believes in the importance of live cover and intends to experiment with new crops, such as a mix of spring/winter barley and rapeseed, to continue improving his farm.

Victor Shelton, a retired agronomist and grazing specialist with the NRCS in Indiana, authored this piece.